Third Intermediate Period of Egypt

Third Intermediate Period of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1077 BC – c. 664 BC | |||||||||

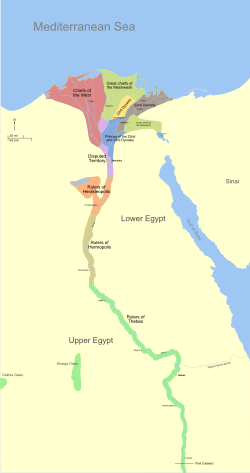

Political factions fractured ancient Egypt during the Third Intermediate Period. The boundaries above show the political situation during the mid-8th century BC. | |||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||

• c. 1077–1052 BC | Smendes (first) | ||||||||

• c. 664–656 BC | Tantamani (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Began | c. 1077 BC | ||||||||

• Ended | c. 664 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Egypt Sudan | ||||||||

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

The Third Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt began with the death of Pharaoh Ramesses XI in 1077 BC, which ended the New Kingdom, and was eventually followed by the Late Period. Various points are offered as the beginning for the latter era, though it is most often regarded as dating from the foundation of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty by Psamtik I in 664 BC, following the departure of the Nubian Kushite rulers of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty after they were driven out by the Assyrians under King Ashurbanipal. The use of the term "Third Intermediate Period",[1] based on the analogy of the well-known First and Second Intermediate Periods, was popular by 1978, when British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen used the term for the title of his book on the period. While Kitchen argued that the period was 'far from being chaotic' and hoped that his work would lead to the abolishment of the term, with his own preference being the 'Post-Imperial epoch', his use of the term as a title seems only to have entrenched the use of the term.[2]

The period was ruled by non-native Egyptians and is viewed as one of decline and political instability including division of the state, coinciding with the Late Bronze Age collapse of civilizations in the ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean (including the Greek Dark Ages).

History

[edit]Twenty-first Dynasty

[edit]The period of the Twenty-first Dynasty is characterized by the country's fracturing kingship. Already during Ramesses XI's reign, the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt was losing its grip on the city of Thebes, whose priests were becoming increasingly powerful. After his death, his successor, Smendes I, ruled from the city of Tanis, but was mostly active only in Lower Egypt, which he controlled. Meanwhile, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes ruled Middle and Upper Egypt in all but name.[2] However, this division was less significant than it seems, since both the priests and pharaohs came from the same family.[citation needed]

Twenty-second and Twenty-third Dynasty

[edit]The country was firmly reunited by the Twenty-second Dynasty founded by Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC), who descended from Meshwesh immigrants, originally from ancient Libya.[a] This brought stability to the country for well over a century, but after the reign of Osorkon II, particularly, the country had effectively split into two states, with Shoshenq III of the Twenty-second Dynasty controlling Lower Egypt by 818 BC while Takelot II and his son Osorkon (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt. In Thebes, a civil war engulfed the city, pitting the forces of Pedubast I, who had proclaimed himself pharaoh, against the existing line of Takelot II/Osorkon B. The two factions squabbled continuously and the conflict was only resolved in Year 39 of Shoshenq III when Osorkon B comprehensively defeated his enemies. He proceeded to found the Upper Egyptian Libyan Twenty-third Dynasty of Osorkon III – Takelot III – Rudamun, but this kingdom quickly fragmented after Rudamun's death, with the rise of local city states under kings such as Peftjaubast of Herakleopolis, Nimlot of Hermopolis, and Ini at Thebes.

Twenty-fourth Dynasty

[edit]The Nubian kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and the ensuing political instability. Prior to Piye's Year 20 campaign into Egypt, the previous Nubian ruler – Kashta – had already extended his kingdom's influence into Thebes when he compelled Shepenupet, the serving Divine Adoratice of Amun and Takelot III's sister, to adopt his own daughter Amenirdis, to be her successor. Then, 20 years later, around 732 BC his successor, Piye, marched north and defeated the combined might of several native Egyptian rulers: Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, Iuput II of Leontopolis and Tefnakht of Sais.

Twenty-fifth Dynasty

[edit]

Piye established the Twenty-fifth Dynasty and appointed the defeated rulers as his provincial governors. He was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa. The reunited Nile valley empire of the 25th Dynasty was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom. Pharaohs of the dynasty, among them Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including at Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal.[5][6] The 25th Dynasty ended with its rulers retreating to their spiritual homeland at Napata. It was there (at El-Kurru and Nuri) that all 25th Dynasty pharaohs were buried under the first pyramids to be constructed in the Nile valley in hundreds of years.[7][8][9][10] The Napatan dynasty led to the Kingdom of Kush, which flourished in Napata and Meroe until at least the 2nd century AD.[7]

The international prestige of Egypt had declined considerably by this time. The country's international allies had fallen firmly into the sphere of influence of Assyria and from about 700 BC the question became when, not if, there would be war between the two states as Esarhaddon had realised that a conquest of Lower Egypt was necessary to protect Assyrian interests in the Levant.

Despite Egypt's size and wealth, Assyria had a greater supply of timber, while Egypt had a chronic shortage, allowing Assyria to produce more charcoal needed for iron-smelting and thus giving Assyria a greater supply of iron weaponry. This disparity became critical during the Assyrian invasions of Egypt over the period 670–663 BC.[11] Consequently, pharaoh Taharqa's reign, and that of his successor Tantamani, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians. In 664 BC the Assyrians delivered a mortal blow, sacking Thebes and Memphis. Following these events, and starting with Atlanersa, no Kushite ruler would ever rule over Egypt again.

End of the Third Intermediate Period

[edit]Upper Egypt remained for a time under the rule of Taharqa and Tantamani, whilst Lower Egypt was ruled from 664 BC by the nascent 26th Dynasty, client kings established by the Assyrians. In 663 BC, Tantamani launched a full-scale invasion of Lower Egypt, taking Memphis in April of this year, killing Necho I of Sais in the process as Necho had remained loyal to Ashurbanipal. Tantamani barely had the time to receive the submission of some Delta kinglets and expel the remaining Assyrians that a large army led by Ashurbanipal and Necho's son Psamtik I came back. Tantamani was defeated north of Memphis and Thebes was thoroughly sacked shortly after. The Kushite king withdrew to Nubia while the Assyrian influence in Upper Egypt quickly waned. Permanently weakened by the sack, Thebes peacefully submitted itself to Psamtik's fleet in 656 BC. To affirm his authority, Psamtik placed his daughter in position to be the future Divine Adoratrice of Amun, thereby also submitting the priesthood of Amun and effectively uniting Egypt. Tantamani's successor Atlanersa was in no position to attempt a reconquest of Egypt as Psamtik also secured the southern border at Elephantine and may even have sent a military campaign to Napata. Concurrently, Psamtik managed to free himself from the Assyrian vassalage while remaining on good terms with Ashurbanipal, possibly owing to an ongoing rebellion in Babylon. By doing so, he brought increased stability to the country during his 54-year reign from the city of Sais beginning the Late Period of ancient Egypt.

Historiography

[edit]The historiography of this period is disputed for a variety of reasons. Firstly, there is a dispute about the utility of a very artificial term that covers an extremely long and complicated period of Egyptian history. The Third Intermediate Period includes long periods of stability as well as chronic instability and civil conflict: its very name rather clouds this fact. Secondly, there are significant problems of chronology stemming from several areas, there are the difficulties in dating that are common to all of Egyptian chronology and are compounded by synchronisms with Biblical archaeology that also contain heavily disputed dates.

Fringe theories

[edit]Peter James, along with several other academics, argued contra Kitchen that the period lasted less than 200 years, starting later than 850 BC but ending at the conventional date, as the five dynasties had many years of overlap.[12] Some theorists such as David Rohl have controversial theories about the family relationships of the dynasties comprising the period.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schneider, Thomas (27 August 2008). "Periodizing Egyptian History: Manetho, Convention, and Beyond". In Klaus-Peter Adam (ed.). Historiographie in der Antike. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 181–197. ISBN 978-3-11-020672-2. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ a b Kenneth A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 3rd edition, 1986, Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd, pp.xi-xii, 531.

- ^ "Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt Vol. 46(2010)". American Research Center in Egypt. 2010: 170.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Journal of Egyptian History 11 (2018)". Brill. 2018: 147.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ a b Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York, NY: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa. Oxford: Macmillan Education. p. 40. ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ^ "Centuries of Darkness: Context, Methodology and Implications [Review Feature]" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 1 (2): 228ff. 1991. doi:10.1017/S0959774300000378. ISSN 1474-0540. S2CID 246638930. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-12. Retrieved 2018-02-11.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dodson, Aidan Mark. 2001. "Third Intermediate Period." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 3 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 388–394.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. [1996]. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). 3rd ed. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited.

- Myśliwiec, Karol. 2000. The Twilight of Ancient Egypt: First Millennium B.C.E. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Porter, Robert M. 2008. A Network of 22nd–26th Dynasty Genealogies, JARCE 44, 153–157.

- Taylor, John H. 2000. “The Third Intermediate Period (1069–664 BC).” In The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, edited by Ian Shaw. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 330–368.

External links

[edit]- Allen, James, and Marsha Hill. "Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period (1070–712 B.C.)", In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2004)

- Images

Egyptian third intermediate period.

- Artabase.net: Face from a Coffin Archived 2014-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Artabase.net: Right Hand from an Anthropoid Coffin Archived 2014-09-10 at the Wayback Machine