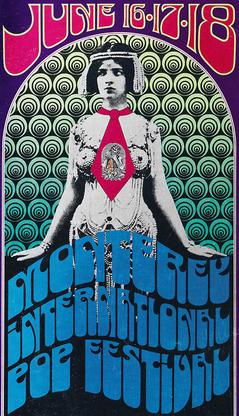

Monterey International Pop Festival

| Monterey International Pop Festival | |

|---|---|

Art by Tom Wilkes | |

| Genre | Rock, pop and folk, including blues rock, folk rock, hard rock and psychedelic rock styles. |

| Dates | June 16–18, 1967 |

| Location(s) | Monterey County Fairgrounds, Monterey, California |

| Coordinates | 36°35′40″N 121°51′46″W / 36.59444°N 121.86278°W |

| Years active | 1967 |

| Founders | Derek Taylor, Lou Adler, John Phillips, Alan Pariser |

The Monterey International Pop Festival was a three-day music festival held June 16 to 18, 1967, at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California.[1] The festival is remembered for the first major American appearances by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Who and Ravi Shankar, the first large-scale public performance of Janis Joplin and the introduction of Otis Redding to a mass American audience.

The festival embodied the theme of California as a focal point for the counterculture and generally is regarded as one of the beginnings of the "Summer of Love" in 1967 and the public debut of the hippie, flower power and flower children movements and era.[2] Because Monterey was widely promoted and heavily attended, featured historic performances, and was the subject of a popular theatrical documentary film, it became an inspiration and a template for future music festivals, including the Woodstock Festival two years later. Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner said "Monterey was the nexus – it sprang from what the Beatles began, and from it sprang what followed."[3]

Background

[edit]

In early 1967, Michael Bowen produced the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, where many attendees dropped acid for the first time (lysergic acid diethylamide or LSD) and listened to Timothy Leary tell the crowd that people living in cities should reorganize as tribes and villages.[4] This was one of the important precursors to the Summer of Love five months later. The Human Be-In directly inspired the Monterey International Pop Festival.[5]

The first American hippie-style rock festival was held during June 10–11 at Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, California, produced by radio station KFRC as the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival. Star performers included the Doors, the Sons of Champlin, Moby Grape, the Steve Miller Blues Band, Jefferson Airplane, Hugh Masekela, Country Joe and the Fish, Canned Heat and the Byrds; the latter seven acts also played Monterey Pop one week later.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Planning

[edit]We are holding a large pop festival here in June and we hope you can all come. ... Already booked: the Byrds, the Buffalo Springfield, the Jefferson Airplane and numerous of the Tomorrow groups now flourishing on the psychedelic San Francisco scene (what DOES psychedelic mean?) ... [I]t should be great too because nothing like this has ever been done and if pop music was ready, it is now and there never was a time like the present anyway.[12]

– Derek Taylor, Disc and Music Echo, March 25, 1967

The festival was planned in seven weeks by John Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas, record producer Lou Adler, Alan Pariser and publicist Derek Taylor. Monterey and Big Sur had been known as the site for the long-running Monterey Jazz Festival and Big Sur Folk Festival; the promoters saw a notional Monterey Pop festival as a way to validate rock music as an art form in the way in which jazz and folk were regarded.[13] Taylor announced the festival on March 25, 1967, in his regular column for Disc and Music Echo magazine.[14][12] The festival's board of governors included some such as Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy who displayed initial enthusiasm but did little to organize the event.[15] Local Big Sur resident and Stage Manager for the Monterey Jazz Festival, Paul Vieregee[16] was brought in to be the Stage Manager for the Monterey Pop Festival, along with McCune Sound for production.

The artists performed for free, with all revenue donated to charity, except for Ravi Shankar, who was paid $3,000 for his afternoon-long performance on the sitar. Country Joe and the Fish were paid $5,000, not by the festival, but from revenue generated from the D. A. Pennebaker documentary, Monterey Pop.[17] The artists did, however, have their flights and accommodation paid for. Apart from Shankar, each act was given up to 40 minutes for their performance. Several ended their sets earlier, including the Who, who played for only 26 minutes.

Monterey's bill boasted a lineup that put established stars like the Mamas and the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, Jefferson Airplane and the Byrds alongside groundbreaking new acts from the UK and the U.S.[18]

Crowd estimates for the festival have ranged from 25,000 to 90,000 people, which congregated in and around the festival grounds.[19][20][21] The fairgrounds' enclosed performance arena, where the music took place, had an approved festival capacity of 7,000, but it was estimated that 8,500 jammed into it for Saturday night's show, with many extra attendees standing around the sides of the arena.[22] Festival-goers who wanted to see the musical performances were required to have either an 'all-festival' ticket or a separate ticket for each of the five scheduled concert events they wanted to attend in the arena: Friday night, Saturday afternoon and night, and Sunday afternoon and night. Ticket prices varied by seating area, and ranged from $3 to $6.50 ($27–59 in 2024, adjusted for inflation).[23][18]

The song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" was written by Phillips and sung by Scott McKenzie, released in May 1967, to promote the event.[24]

Performances

[edit]Friday night

[edit]The Los Angeles–based band the Association with hits such as "Along Comes Mary" and "Never My Love" was the first act to perform at the festival. Newsweek magazine's reporter Michael Lydon reviewed their performance as having a "professional style and entertaining manner," especially on their latest hit single "Windy", which was rising steadily on the Billboard Hot 100.[15]

The Association was followed by the Paupers, a rock band from Toronto, who delivered a "screaming volume and a racy quality," according to Lydon. The Paupers were proud to be judged on their music alone, not relying on "gimmicks" or lighting effects.[15]

The next act was blues singer Lou Rawls fronting a big band, the song arrangements conveying a "rock 'n' soul" style. Rawls also spoke to the crowd about the gritty experiences of African American life. After his set, he said to reporters that he was confident that "the blues is the way of the future. The fads come and go, but the blues remain. The blues is the music that makes a universal language." He described how rock artists were increasingly drawing from the blues to give their music more substance.[15]

Beverley Martyn sang a short set followed by Johnny Rivers. After Rivers was Eric Burdon leading his new incarnation of the Animals, introduced as the New Animals, re-interpreted the Stones song "Paint It Black", adding electric violin.[15] With this appearance, Burdon signaled a change to more of a politically charged hard rock style mixed with psychedelia. He later wrote the song "Monterey" about his experience at the concert.

The headliner of Friday night was Simon & Garfunkel, who started after midnight, and performed minimally with just two voices and one guitar. They finished at 1:30 am on Saturday morning. Lydon reviewed their set as sweetly retrospective, but "they seemed sadly left behind" by the shifting of rock music away from the duo's established folk rock style.[15]

Saturday afternoon

[edit]

Canned Heat started the Saturday afternoon show; their set was deemed "uninspired" by Lydon. In a thrilling display of raw emotion, Janis Joplin sang next, backed by Big Brother and the Holding Company. Joplin's wildly elemental interpretation of the blues standard "Ball and Chain" was described by Lydon as "the blues big mama style, tough, raw, and gutsy, and with an aching that few black singers reach." For the first time at Monterey Pop, the audience rose to their feet.[15] This Saturday set was not recorded by filmmaker Pennebaker, so the group was asked to play again on Sunday night. San Francisco Examiner music critic Phil Elwood wrote that Joplin proved to be "the real queen of the festival".[25] This ended up being Joplin's breakout appearance, bringing her fame far beyond the San Francisco Bay Area. Columbia Records signed Big Brother and the Holding Company on the basis of their performance at Monterey.[26][27]

Country Joe and the Fish came next, delivering a funny performance with an anti-war message. Guitarist and songwriter Barry Melton said afterward that he put political messages in the band's music because "we feel that in this society, you have to make your stance clear. Others don't want to speak up in songs, be right up front." Melton said that taking LSD was part of his "liberation", allowing him to draw from many different musical genres. "When I hear a sound that is groovy I use it. I try to find music all over the place. Listening to anything can give you musical ideas. That's freedom, and maybe that's psychedelic."[15]

Organist Al Kooper sang and played two extended songs for a half hour, followed by the Butterfield Blues Band who were appraised by Lydon as reinvigorating the crowd with "precisely" interpreted blues without being "uptight". One of Paul Butterfield's standout harmonica solos was described as an exercise in serialism, breaking a "few notes into tiny bits and experiment[ing] with their regroupings."[15] The next two bands were dismissed by Lydon as forgettable sets: Quicksilver Messenger Service and the Steve Miller Band.[15]

The final set of Saturday afternoon was the Electric Flag, a band led by guitarist Mike Bloomfield, containing Buddy Miles on drums, Barry Goldberg on organ, and Nick Gravenites singing in front. Their act was hailed as a "smash success" by Lydon. David Crosby announced later that night that if anyone in the audience had failed to see Electric Flag play, "man, you are out of it, so far out of it."[15]

Saturday night

[edit]Moby Grape kicked off Saturday evening's concert with an unmemorable performance, according to Lydon.[15] Due to legal and managerial disputes, the group was not included in the Pennebaker-produced film. Some of the Moby Grape footage was shown in 2007 as part of the 40th anniversary celebration of the film. An outtake of Moby Grape's performance of "Hey Grandma" appears on the bonus disc of the Criterion release of the film. Regarding the decision for Moby Grape to open the evening, guitarist Jerry Miller recalled that "everybody was arguing. Nobody wanted to play first and I said that would be fine for me."[28]

Moby Grape was followed by a "terrible" showing by South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela, helped only by a spirited display by Danny "Big Black" Rey on the congas.[15] The Byrds sang some hits and some new songs, but did not energize the crowd.[15] The band ended with a new single, "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", featuring Masekela on trumpet, reprising his participation in the studio recording.

A 20-year-old Laura Nyro gave one of her earliest performances at the Monterey Pop Festival. Lydon wrote that Nyro's "melodramatic" set, "accompanied by two dancing girls who pranced absurdly", was a disaster during which "the evening hit bottom".[15] Other critics wrote that the black-gowned Nyro was out of sync with the psychedelic sensibilities of the event. Upon the conclusion of her set, Nyro was upset, having heard booing from the audience. While reviewing the raw footage in the 1990s, Pennebaker picked out an audience member saying "beautiful", and invited Nyro to witness it, but she died before this could be arranged.[29]

With two huge singles behind them, San Francisco–based Jefferson Airplane was one of the major attractions of the festival, having built a large following on the West Coast. Lydon wrote that the band "thoroughly proved themselves" masters of psychedelia, aided by a trippy Headlights liquid light show projected overhead, enticing hundreds to join the band on stage dancing. Grace Slick "sang as if possessed" while she swayed in a full-length blue robe.[15]

After this, Booker T. & the M.G.'s played a handful of instrumental R&B tunes, wearing brilliant lime green suits, then they were joined by an identically attired Otis Redding who electrified the audience with his sexually charged singing style. He sang his 1965 song "Respect" which was topping the charts because of a popular new interpretation by Aretha Franklin. Redding finished with a riveting "Try a Little Tenderness". The crowd responded by standing and screaming for more.[15] Redding had been included on the bill through the efforts of promoter Jerry Wexler, who saw the festival as an opportunity to advance Redding's career.[26] Until that point, Redding had performed mainly for black audiences,[27] besides a few successful shows at the Whisky a Go Go. Redding's show, received well by the audience ("there is certainly more audible crowd participation in Redding's set than in any of the others filmed by Pennebaker that weekend") included a version of the Stones' "Satisfaction".[30] The festival would be one of his last major performances: Redding died only six months later, in a plane crash, at the age of 26.

Sunday afternoon

[edit]Ravi Shankar was another artist who was introduced to the U.S. at the festival. Shankar's set began Sunday afternoon following a rainy morning, and the audience filled the arena to about 80% capacity. All other musical acts played to a packed house.[31] He and his group of East Indian instrumentalists played for three hours, after asking everyone to refrain from photography and smoking.[15] Shankar performed several ragas,[31] two of which were released on the album Live: Ravi Shankar at the Monterey International Pop Festival. A dhun based on the raga Panchamse-Ghara (later miscredited as raga Bhimpalasi) concluded the Monterey Pop film.

Sunday night

[edit]The Blues Project opened the final night of the festival. Lydon said that their blues fusion music was "part blues, part Scottish air, part weird phrases that became images of ambiguity."[15] Big Brother and the Holding Company returned for a short set designed to capture on film Janis Joplin singing "Ball and Chain". A team led by Cyrus Faryar, called Group With No Name, played a "terrible" set, as judged by Lydon.[15] Buffalo Springfield, introduced by Peter Tork of the Monkees, appeared with a competent and efficient delivery of a half dozen songs, with "Bluebird" called out as memorable.[15]

Although already a big act in the UK, and now gaining some attention in the U.S. after playing some New York dates two months earlier, the Who were propelled into the American mainstream at Monterey. The band used rented Sound City amps for their set, which were not as powerful as their regular Vox amps which they had left in England to save shipping costs. At the end of their frenetic performance of "My Generation", the audience was stunned as guitarist Pete Townshend smashed his guitar and slammed the neck against the amps and speakers. Smoke bombs exploded behind the amps and frightened concert staff rushed onstage to retrieve expensive microphones. At the end of the mayhem, drummer Keith Moon kicked over his drum kit as the band exited the stage. During Jimi Hendrix's stay in England, he and the Who had seen each other perform; they were both impressed with and intimidated by each other, so neither wanted to be upstaged by the other. They decided to toss a coin, resulting in the Who winning the right to play first.[32]

The festival crew cleared the mess left behind by the Who, and set the stage for the Grateful Dead. While a psychedelic light show was projected overhead, the band, fronted by lead guitarist and singer Jerry Garcia, played extended jams, starting with "Viola Lee Blues" for 14 minutes, and finishing with a 20-minute segue of "Alligator" into "Caution (Do Not Stop on Tracks)". Lydon commented: "The Grateful Dead were beautiful. They did at top volume what Shankar had done softly. They played pure music, some of the best music of the concert. I have never heard anything in music that could be said to be qualitatively better than the performance of the Dead, Sunday night.[15]

Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones introduced the Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Monterey Pop Festival on the evening of Sunday, June 18. Jimi Hendrix's use of extremely high volumes, the feedback this produced, and the combination of the two along with his dive-bombing use of the vibrato bar on his guitar, produced sounds that, with the exception of the British in attendance, none of the audience had ever heard before. This, along with his look, his clothing, and his erotic antics onstage, had an enormous impact on the audience. To take things further, aware of the Who's planned explosive finale, he asked around for a can of lighter fluid, which he placed behind one of his amplifier stacks before beginning his set. He ended his Monterey performance with an unpredictable version of "Wild Thing", which he capped by kneeling over his guitar, pouring lighter fluid over it, setting it on fire, and then smashing it onto the stage seven times before throwing its remains into the audience.[26] This performance put Hendrix on the map and generated an enormous amount of attention in the music press and newspapers alike.[33] Robert Christgau later wrote in The Village Voice of Hendrix's performance:

Music was a given for a Hendrix stuck with topping The Who's guitar-smashing tour de force. It's great sport to watch this outrageous scene-stealer wiggle his tongue, pick with his teeth, and set his axe on fire, but the showboating does distract from the history made that night—the dawning of an instrumental technique so effortlessly fecund and febrile that rock has yet to equal it, though hundreds of metal bands have gotten rich trying. Admittedly, nowhere else will you witness a Hendrix still uncertain of his divinity.[34]

Backstage before their sets, Hendrix played his guitar while staring at guitarist Pete Townshend, who denied the assumption that they were jamming together. Townshend said later, "It was just Jimi on a chair playing at me. Playing at me like 'Don't fuck with me, you little shit.'"[35]

The Mamas & the Papas closed the festival. They also brought on Scott McKenzie to play his John Phillips–written single "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)". Their set included their hits "Monday, Monday" and "California Dreamin'". The song "Dancing in the Street" was the final song performed at the festival, with Mama Cass telling the audience "You're on your own".

After the concert, members of Jefferson Airplane, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and the Grateful Dead jammed together backstage for four more hours, stopping for breakfast at dawn.[15]

No-shows

[edit]The Beach Boys

[edit]

The Beach Boys' Brian Wilson was among the festival's board members.[37] His group was, at one point, slotted to perform after the Byrds on June 17, the second evening of the event.[38] During mid–1967, the Beach Boys were struggling with numerous personal and professional issues. At the last minute, they announced that they could not play the gig due to Carl Wilson's dispute with officials over his refusal to be drafted into military service, as well as the band's commitments to finishing the long-overdue "Heroes and Villains" single for Capitol Records.[39]

Another (unofficial) reason given for the band's cancellation was that Brian had had disagreements with the promoter.[40] Carl later commented: "Brian was on the board and [the festival] changed several times, the concept of it, and he decided 'This is shit, let's not play it.' I think there were some people getting hostile about the group at the time, about the surfing thing and he figured, 'Fuck you,' or something like that."[41] Asked about the decision, Bruce Johnston said "it went from 'Here's the money, here's the offer, you're headlining' to 'Now this is gonna be a non-profit show' so we pulled out."[42] Other issues plaguing the group involved Brian and Dennis Wilson's drug use.[43]

Many of the people involved with the festival thought that the group was simply too scared to compete with the "new music".[44] Derek Taylor, who had previously worked as their publicist, presumed that "it had to be down to Brian. Those sorts of decision were always his, really."[45] John Phillips told a reporter that "Brian was afraid that the hippies from San Francisco would think The Beach Boys were square and boo them."[39] Wilson's assistant Michael Vosse recalled that Wilson thought the Beach Boys would have been criticized by festival goers who were intent on seeing British acid rock groups.[46] Writer David Leaf posited that the band dropped out because they had no fitting material in their repertoire besides "Good Vibrations".[47]

Mike Love stated that none of the band members "were afraid to perform at Monterey" and explained that "Carl was to appear in federal court the Tuesday after the concert, but for all we knew, they were going to arrest him again if he performed onstage ... ".[48] In a 1974 interview, he stated that he was "ready to go", but Brian "got sort of cold feet on the situation because he didn't trust that the people there in that organization were going to do right with the money and everything, and sure enough there was a scandal about that about a year or two after."[49] Stephen Desper, who was a sound engineer for the event, wrote that the band dropped out due to Love's objections toward Coca-Cola, one of the event's sponsors.[50] In 2017, Love reflected that drugs were influencing the band's decisions at the time and maintained that pulling out of Monterey was not his doing.[51]

In the week after the festival had occurred, Brian traveled to the Monterey County Fairgrounds to pick up programmes of the event.[52] According to journalist Domenic Priore, the band attempted to "make up for their non-appearance" by recording a live album, Lei'd in Hawaii, but it was never released.[53]

The Beach Boys' sudden cancellation drew much criticism from the music press, and it had a long-lasting impact on critics' opinions of the group.[36] Taylor remembered that dropping out of the program "undoubtedly set the band in a very bad light. They were certainly heavily criticized at the time for it. It seemed rather like an admission of defeat."[45] Biographer Steven Gaines writes that the band's cancellation "had a snowballing effect" that came to represent "a damning admission that [they] were washed up".[44] In the description of Pitchfork contributor Jesse Jarnow, "when the band pulled out of their performance, the ascendant underground effectively wrote the Beach Boys—one of the biggest American hitmakers of the decade—out of the '60s rock narrative that followed."[54]

Other

[edit]- Donovan was mentioned as a possible attendee in Taylor's original March 25, 1967, press release,[14][12] but he was refused a visa to enter the United States because of a 1966 drug charge.[55]

- The Kinks were also mentioned in Taylor's press release,[14][12] but the band declined the invitation after anticipating issues obtaining U.S. work visas.[56] Due to incidents during the band's 1965 US tour, the US musicians' union blacklisted them from American performance until 1969.[57]

- The Lovin' Spoonful were invited but declined because of a marijuana investigation and resulting bandmember changes.[15]

- Dionne Warwick canceled her appearance shortly before the festival.[15]

- The Monkees, despite being the biggest selling act of 1967, were never in any serious consideration to play,[citation needed] although band members Micky Dolenz and Peter Tork did attend the festival.[citation needed] Dolenz can be seen in footage during Ravi Shanker's performance while Tork introduced Buffalo Springfield.

Influence

[edit]

The festival launched the careers of many who played there, making some of them into stars virtually overnight, including Janis Joplin.[58]

Monterey was also the first high-profile event to mix acts from major regional music centers in the U.S. – San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Memphis, Tennessee, and New York City – and it was the first time many of these bands had met each other in person. It was a particularly important meeting place for bands from the Bay Area and L.A., who had tended to regard each other with a degree of suspicion, and until that point the two scenes had been developing separately along fairly distinct lines. Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane said "The idea that San Francisco was heralding was a bit of freedom from oppression."[59]

Monterey also marked a significant changing of the guard in British music. The Who and Eric Burdon and the Animals represented the UK, with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones conspicuously absent.[55] The Stones' Brian Jones was seen many times strolling through the crowds, resplendent in full psychedelic regalia, and appeared on stage briefly to introduce Jimi Hendrix. It would be two more years before the Stones went on tour, by which time Jones was dead. The Beatles had already stopped touring altogether. Meanwhile, the Who's striking performance brought them widespread fame in the US.

Also notable was the festival's innovative sound system, designed and built by audio engineer Abe Jacob, who started his career doing live sound for San Francisco bands and went on to become a leading sound designer for the American theater. Jacob's groundbreaking Monterey sound system was the progenitor of all the large-scale PAs that followed.[citation needed] It was a key factor in the festival's success and it was greatly appreciated by the artists—in the Monterey film, David Crosby can clearly be seen saying "Great sound system!" to bandmate Chris Hillman at the start of the Byrds' soundcheck. Lighting by Chip Monck attracted the attention of the Woodstock Festival promoters.[60]

Electronic music pioneers Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause set up a booth at Monterey to demonstrate the new electronic music synthesizer developed by Robert Moog.[61] Beaver and Krause had bought one of Moog's first synthesizers in 1966 and had spent a fruitless year trying to get someone in Hollywood interested in using it. Through their demonstration booth at Monterey, they gained the interest of acts including the Doors, the Byrds, the Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, and others. This quickly built into a steady stream of business, and the eccentric Beaver was soon one of the busiest session men in L.A. He and Krause earned a contract with Warner Brothers.

Eric Burdon and the Animals later that same year, in their hit "Monterey", quoted a line from the Byrds' song "Renaissance Fair" ("I think that maybe I'm dreamin'") and mentioned performers the Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, Ravi Shankar, Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Hugh Masekela, Grateful Dead, and the Rolling Stones' Brian Jones ("His Majesty Prince Jones smiled as he moved among the crowd"). The instruments used in the song imitate the styles of these performers.

Anniversary festival

[edit]The festival did not become an annual event. However, in 2017 on the 50th anniversary of the festival, the "Monterey International Pop Festival – Celebrates 50 Years" was held at the same venue on the same weekend, with the participation of Lou Adler. Norah Jones, daughter of Ravi Shankar, was one of the headliners.[62]

Recording and filming the festival

[edit]The festival was the subject of a documentary movie titled Monterey Pop by noted documentary filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker. Pennebaker's team used recently developed portable 16mm crystal-sync motion picture cameras that stayed synchronized with double-system sound-recording systems. The film stock was Eastman Kodak's recently released "high-speed" 16mm Ektachrome 100 ASA color reversal motion picture stock, without which the nighttime shows would have been virtually impossible to shoot in color. Sound was captured by Wally Heider's mobile studio on a then state-of-the art eight-channel recorder, with one track used for the crystal-sync tone, to synchronize it with the film cameras. The Grateful Dead believed that the film was too commercial and refused permission for their performance to be shown.[citation needed] The screening of the film in theaters nationwide helped raise the festival to mythic status, rapidly swelled the ranks of festival-goers looking for the next festival, and inspired new entrepreneurs to stage more such festivals around the country. Adler said the cameramen were instructed to capture at least two complete songs for most of the acts, but for certain others, particularly the Who and Hendrix, to film as much of the sets as possible. As a result, only one song was not captured in part at least from both acts' performances.

Big Brother's scheduled set was not filmed because of a disagreement. However, due to the huge reaction the band got, they were asked to return to play two songs on Sunday, to be filmed specifically for the movie.

An expanded version of the documentary has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection.[63]

The audio recordings of the festival eventually became the basis for many albums, most notably the 1970 release Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International Pop Festival featuring partial sets by Otis Redding and Jimi Hendrix. Other releases recorded at the festival included dedicated live albums by Ravi Shankar in 1967 and Jefferson Airplane in 1991. In 1992, a four-CD box set was released featuring performances by most of the artists; various other compilations have been released over the years. According to a radio promotional feature that accompanied the box-set release, on modified stages, including flatbed Kaleidscope (LA) trucks, set up in the surrounding environs, there had been several spontaneous jam sessions for the overflow crowds and campers. Among them was one at the Monterey Peninsula Community College sports stadium (right across the Hwy. 1 interchange), where Jimi Hendrix, flanked by Jorma Kaukonen and John Cipollina, played for an enthusiastic audience.

Performers

[edit]|

Friday, June 16 |

Saturday, June 17

(evening) |

Sunday, June 18 (evening)

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Monterey International Pop Festival". www.montereyinternationalpopfestival.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Walser, Robert. L. Macy (ed.). "Pop III, North America. 3. 1960s". Grove Music Online. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney, Waiting for the Sun, St. Martin's Press, 1996, pg. 146

- ^ Katz, Don (1992). Home Fires. Aaron Asher Books. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-06-019009-5.

- ^ Johnson, Evie (2019). "Human Be-In, 1967". FoundSF. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry (1970). Festival! The Book of American Music Celebrations. New York: Macmillan Company. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-02-061950-5. OCLC 84588.

- ^ Nicholson, John (May 2009). "A History of Rock Festivals". Rock Solid Music Magazine. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising – The Rock Festival Years. Pg. 16.

- ^ Lang, Michael (June 30, 2009). The Road to Woodstock (p. 58). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Browne, David. (June 5, 2014). "The Birth of the Rock Fest". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey and Kubernik, Kenneth. A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival. 2011. Santa Monica Press LLC. Pg. 54.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Derek (March 25, 1967). "Our Man in America: Stones, Kinks, Donovan and Who for U.S. Show?". Disc and Music Echo. p. 14.

- ^ "Lou Adler interview". The Tavis Smiley Show. PBS. June 4, 2007. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1987, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Lydon, Michael (September 22, 2009). "Monterey Pop: The First Rock Festival". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved June 20, 2022. Originally written in 1967 for Newsweek magazine, whose editors reduced it from 43 to 10 paragraphs. Printed in full in the 2003 book Flashbacks ISBN 9780415966443.

- ^ "A Noteworthy Connection: How Monterey Jazz Fest helped inspire Monterey Pop". April 14, 2017.

- ^ Sander, Ellen (1973). Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties, p.93. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-12752-1.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (January 1969). "Anatomy of a Love Festival". Esquire. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ Grunenberg, Christoph; Harris, Jonathan (2005). Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s. Liverpool University Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-85323-929-1. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Santelli, Robert. Aquarius Rising – The Rock Festival Years. 1980. Dell Publishing Co., Inc. Pg. 264.

- ^ Lang, Michael (June 30, 2009). The Road to Woodstock (p. 53). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising – The Rock Festival Years. Pp. 22, 44.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising – The Rock Festival Years. Pp. 25–26, 32, 41.

- ^ Davis, Clive (February 19, 2013). "8: Monterey Pop". The Soundtrack of My Life. Simon & Schuster. pp. 62–64. ISBN 9781476714790.

- ^ Phil Elwood, “Dreams Come True in Monterey,” San Francisco Examiner, June 19, 1967

- ^ a b c Miller, James (1999). Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80873-4. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ a b Echols, Alice (2000). Scars of sweet paradise: the life and times of Janis Joplin. Macmillan. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8050-5394-4.

- ^ "Mods & Rockers Festival: Grapeful for Monterey". July 18, 2007.

- ^ Soul Picnic: The Music and Passion of Laura Nyro by Michelle Kort. Pages 41-45 and 248.

- ^ Inglis, Ian (2006). Performance and popular music: history, place and time. Ashgate. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-7546-4057-8.

- ^ a b "Monterey Pop Fest: Weekend to Remember". Cash Box. July 1, 1967. p. 7, 46.

- ^ "Pete Townshend Recalls Negotiating with Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop Festival". Ultimate Classic Rock.

- ^ Lochhead, Judith (Summer 2001). "Hearing Chaos". American Music. 19 (2): 237. doi:10.2307/3052614. JSTOR 3052614.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (July 18, 1989). "Reluctant Rockumentarist". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Wardlaw, Matt. "Pete Townshend Recalls Negotiating with Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop Festival". Ultimate Classic Rock.

- ^ a b Badman 2004.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 180, 189.

- ^ White 1996, p. 274.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 189.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 191.

- ^ Sharp, Ken (September 4, 2013). "Bruce Johnston On the Beach Boys' Enduring Legacy (Interview)". Rock Cellar Magazine. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ Sharp, Ken (November 1, 2013). "Brian Wilson, Al Jardine, Mike Love - The Interview". Rock Cellar Magazine. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Gaines 1986, p. 179.

- ^ a b Kent 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 178.

- ^ Leaf, David (1990). Smiley Smile/Wild Honey (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 170.

- ^ "The Beach Boys Story: Episode 4: Smile and Meditation". BBC (Audio). 1974.

- ^ Desper, Stephen (December 24, 2015). "Re: The Stephen Desper Thread". Smileysmile.com.

- ^ Sharp, Ken (December 13, 2017). "Mike Love Interview Part 5". Rock Cellar Magazine (Interview: Video). Interviewed by Mike Love. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 193.

- ^ Priore, Domenic (2005). Smile: The Story of Brian Wilson's Lost Masterpiece. London: Sanctuary. p. 125. ISBN 1-86074-627-6. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ^ Jarnow, Jesse (July 1, 2017). "1967 – Sunshine Tomorrow". Pitchfork.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 47 – Sergeant Pepper at the Summit: The very best of a very good year. [Part 3] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

With the exception of the music of Ravi Shankar...songs were recreated.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Greene 2014, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Rodnitzky, Jerry (2002). "Janis Joplin: The Hippie Blues Singer as Feminist Heroine". Journal of Texas Music History. 2 (1): 10.

- ^ Morrison, Craig (Autumn 2001). "Folk Revival Roots Still Evident in 1990s Recordings of San Francisco". The Journal of American Folklore. 114 (454): 480. doi:10.2307/542052. JSTOR 542052. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Mitchell, Kevin. "Chip Monck: Grandfather of Rock and Roll Productions". Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Brend, Mark (2005). Strange Sounds: Offbeat Instruments and Sonic Experiments in Pop. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-87930-855-1. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Monterey International Pop Festival – Celebrates 50 Years, URL accessed February 3, 2018.

- ^ "Monterey Pop". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

General and cited references

[edit]- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Kent, Nick (2009). "The Last Beach Movie Revisited: The Life of Brian Wilson". The Dark Stuff: Selected Writings on Rock Music. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-3074-2.

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806479.

- Greene, Doyle (2014). The Rock Cover Song: Culture, History, Politics. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-7809-5.

- Hinman, Doug (2004). The Kinks: All Day and All of the Night: Day by Day Concerts, Recordings, and Broadcasts, 1961–1996. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-765-3.

- Love, Mike (2016). Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-40886-9.

- Taylor, Derek (1987). It Was Twenty Years Ago Today. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-64201-3.

- White, Timothy (1996). The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys, and the Southern Californian Experience. Macmillan. ISBN 0333649370.

Further reading

[edit]- Carpenter, Julie. "The Summer of Love; It was a time of peace, love and flowers in your hair. But, 40 years on, the hippie ideals of 1967 have had a longer lasting impact than the most far-out dreamer could have predicted." The Express May 25, 2007 U.K. 1st Edition ed.: News30.

- Harrington, Richard. "Recapturing The Magic of Monterey." The Washington Post June 16, 2006 Final Edition ed.: T35.

- Morse, Steve. "Hendrix's guitar was on fire." The Boston Globe November 18, 2007 Third Edition ed.: LivingartsN16.

- Perusse, Bernard. "Ravi Shankar's music intoxicating on its own: Contrary to his music's association with drug culture, the sitar master plays with a focus that would be impossible under the influence." The Gazette October 2, 2003 Thursday Final Edition ed.: Arts&LifeD1.

- "Monterey—they rocked till they dropped." Sunday Age (Melbourne, Australia) June 12, 1994 Late Edition ed.: Agenda1.

External links

[edit]- Monterey Pop Festival Art Director Tom Wilkes

- DVD review – The Complete Monterey Pop Festival (The Criterion Collection)

- Photos of the event

- MUSIC FESTIVALS: III. Monterey: Peace, Love and Flowers

- California Dreaming becomes reality Archived February 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Pop Perfect: Monterey Pop Revisited

- Liner Notes Booklet by Stephen K. Peeples from Grammy-Nominated 1992 Monterey International Pop Festival boxed set

- Links to audio from the Monterey Pop Festival

- 1967 in California

- 1967 music festivals

- California culture

- Concerts in the United States

- Counterculture festivals

- Hippie movement

- History of Monterey County, California

- History of the Monterey Bay Area

- Jam band festivals

- Monterey, California

- Music festivals established in 1967

- Music festivals in California

- Pop music festivals in the United States

- Rock festivals in the United States