Recreation Park (Pittsburgh)

Newspaper sketch of Recreation Park, 1894 | |

| |

| Former names | Union Park 3A Park[b] Coliseum |

|---|---|

| Location | Allegheny City, Pennsylvania (pre-1907) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania[a] (post-1907) |

| Coordinates | 40°27′17″N 80°01′07″W / 40.4547°N 80.0186°W |

| Capacity | 17,000 |

| Surface | Grass |

| Opened | 1865 (as skating rink) 1867 (as ballpark) |

| Tenants | |

| Baseball Pittsburgh Enterprises, Xanthas and Olympics (circa. 1876–circa. 1887) Pittsburgh Allegheny (IA) (1877–1878) Pittsburgh Alleghenys (AA) (1884–1886) Pittsburgh Alleghenys (NL) (1887–1890) Football Western University of Pennsylvania (1898–1904) Pittsburgh Stars (NFL) (1902) | |

| Official name | First Professional Football Game |

| Designated | November 3, 1992[1] |

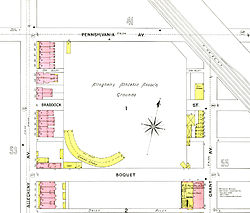

Recreation Park (known at various times as Union Park, 3A Park, and the Coliseum) was a sporting grounds and stadium that stood from 1865 to 1905 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, which was annexed in 1907 and became the North Side region of Pittsburgh. The park was bounded by Allegheny Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue, Grant (now Galveston) Avenue, and Boquet (now Behan) Street.

The field was the first National League home for the Pittsburgh Pirates (at the time referred to as the Alleghenys)[2] of Major League Baseball. It also hosted many football games of the Western University of Pennsylvania (today's University of Pittsburgh). In November 1892, the park hosted the first known American football game that included a professional player.

Only one known photograph, taken from a very distant vantage point, shows the grounds in its longtime baseball configuration. It was discovered in 2015 in a time capsule left by scientific instrument maker John Brashear.[3] A much-altered facility appears in later photos, including several newspaper shots of football games.

History

[edit]Opened in 1865 as a skating center, the park was adapted for baseball use in 1867.[3] Known until 1885 as Union Park,[3] the stadium had an early capacity of 2,500,[2] and was later expanded with wooden grandstands to allow up to 17,000 spectators.[4] After the Alleghenys moved a few blocks south in 1890, the main tenant became the Allegheny Athletic Association, and the grounds would eventually be referred to as 3A Park.[b] After the turn of the 20th century, it was converted to a velodrome called the Coliseum.

In 2001, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Pirates built stadiums not far from this site.

Baseball

[edit]In the late 1860s and early 70s, Pittsburgh was home to three local amateur baseball teams—the Enterprise Club, the Xanthas, and the Olympics—which played most of their games Union Park. In 1876, the professional Allegheny club played its first game against Xantha at Union Park, winning 7–3.[2] Allegheny lasted for three years, playing mostly other squads from the northeast within the International Association, but occasionally taking on National League teams in exhibition games. One long-remembered match took place in early May 1877, when Pud Galvin threw a shutout and hit a home run in a 1–0 victory over the Boston Red Stockings. In 1884, the two-year-old Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the American Association moved from Exposition Park II to Union Park.[5] The team posted a record of 18–37 at home that season, finishing 11th in the league.[6]

The ballpark was used as a neutral site for one game in the 1885 World Series and for one game in the 1887 World Series.

In 1887, owner William A. Nimick transferred the club into the National League,[4] and on April 30, the Alleghenies defeated the Chicago White Stockings, 6–2 in front of 10,000 spectators. This was the first officially recognized contest of the Pittsburgh Pirates franchise.[7] Legend has it that, before opening game of the 1887 season, Pittsburgh's catcher Fred Carroll buried his pet monkey beneath home plate.[4] Also during that season, local businessman Walter Brown organized an early attempt of a league for African American ballplayers, with his Pittsburgh Keystones taking up residence at the park.

In 1891, after the collapse of the Pittsburgh Burghers baseball franchise and the Players' League, the Alleghenys moved to the third incarnation of Exposition Park, which had been constructed for the Burghers.[8]

Football

[edit]On November 12, 1892, the Allegheny Athletic Association football team defeated the Pittsburgh Athletic Club in the first known American football game to feature a professional player.[9] The team had hired Pudge Heffelfinger, an all-American guard from Yale, for $500.[10] Decades later, the Pro Football Hall of Fame discovered a page torn from an 1892 account ledger prepared by Allegheny manager O. D. Thompson with the line item: "Game performance bonus to W. Heffelfinger for playing (cash) $500."[11]

In 1902, a Pirates-backed football team, the Pittsburgh Stars of the first National Football League, played its home games at the field. The Stars would win the league's only championship against the Philadelphia Athletics, 11–0, at the field.[12]

The Western University of Pennsylvania (WUP) football team played their first game of the 1898 season at Recreation Park, defeating Westminster 5–0.[13] Though WUP played some games at Exposition Park as early as 1900,[14] games were hosted at Recreation Park until the University signed an exclusive contract with Exposition Park in 1904.[15]

Cycling

[edit]Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss secured a lease on the park in 1901 to block the upstart American League from establishing a competing baseball franchise in Pittsburgh. To monetize the grounds, Dreyfuss installed a modern bicycle track to be used for motor-paced races featuring the stars of the sport.[16] Baseball umpire and boxing referee Tim Hurst managed the facility,[2] which opened in May 1902 under a name variously spelled as "Colosseum" or "Coliseum." The track, a smooth wooden oval with 20-foot (6 m) bankings, encompassed a multipurpose field. Surrounding the track was new seating for 7,000 spectators, including covered grandstands on the north and south sides and open bleachers.[17] The venture proved a failure: Cycling did not catch on as a spectator sport, and although the stadium found alternative use as a football venue, there was not enough football to bring sufficient revenue.[16] No longer fearing an invasion by the American League,[18] Dreyfuss let the lease expire in April 1904. The track was torn down and the grounds turned back over to the owners.[16]

Other uses

[edit]Beyond simply major sporting events, the park often also doubled as a venue for circuses, carnivals, various ethnic and holiday celebrations, and track meets. Before the Exposition grounds were used for major gatherings, Union Park was a main local gathering place that could easily and closely accommodate large crowds for exhibitors. Popular national figures such as Adam Forepaugh and P. T. Barnum would hold their shows here, spending up to three days before moving off to one-night shows in smaller towns. The park sat next to the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway.

Recreation Park has a reference in the city directory as late as 1914, but the open land was soon covered over by various industrial buildings, since the early 1900s.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The name of Pittsburgh was sometimes spelled without the 'h' during the park's existence.

- ^ a b Other variants of this name included "A. A. A. Park" and "Three A's Park".

References

[edit]- ^ "Pennsylvania Historical Markers Search" (Searchable database). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ^ a b c d Lieb, Frederick (1948). The Pittsburgh Pirates. New York: GP Putnam's Sons reprinted 2003 by Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2492-X.

- ^ a b c Britcher, Craig (Spring 2016). "At Long Last, a Recreation Park Photo Comes to Light". Up Front. Western Pennsylvania History. 99 (1): 6–7.

- ^ a b c "Exposition Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 2006-07-11. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors". Pittsburgh Pirates. BaseballReference.com. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ "1884 Pittsburgh Alleghenys Schedule". Pittsburgh Pirates. BaseballReference.com. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ^ "1887–1900". Pirates Timeline. PittsburghPirates.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Finoli, David; Bill Ranier (2003). The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. United States: Sports Publishing L.L.C. pp. 485–6. ISBN 1-58261-416-4.

- ^ "Nov. 12: Birth of pro football". Pro Football History. ProFootballHOF.com. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ The Birth of Pro Football Archived 2010-11-27 at the Wayback Machine Pro Football Researchers Association

- ^ National Football League NFL History

- ^ Carroll, Bob (1980). "Dave Berry and the Philadelphia Story" (PDF). Coffin Corner. 2 (Annual). Professional Football Researchers Association: 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-18.

- ^ Western University of Pennsylvania. "Foot Ball". Western University courant. 14 (1): 27. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Western University of Pennsylvania. "Athletics". Western University courant. 16 (2): 46. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Alberts, Robert C. (1986). Pitt: The Story of the University of Pittsburgh, 1787–1987. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-8229-1150-7.

- ^ a b c "The Colosseum Track Will Be Destroyed". The Pittsburgh Gazette. 8 April 1904. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The New Bicycle Track". The Pittsburg Post. 19 May 1902. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreyfuss' Doings". Sporting Life. 42 (7): 2. 31 October 1903. (See also "Pittsburg Points" on the same page.)

External links

[edit]- 1893 Sanborn map showing the ballpark

- Flickr album with various photos of the park in its "Colosseum" phase