Margaux Hemingway

Margaux Hemingway | |

|---|---|

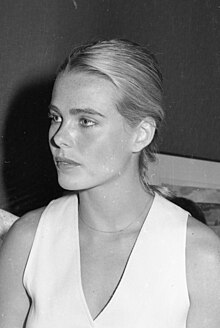

Hemingway in 1976 | |

| Born | Margot Louise Hemingway February 16, 1954 Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1996 (aged 42) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ketchum Cemetery, Ketchum, Idaho, U.S. 43°41′13″N 114°22′00″W / 43.686806°N 114.366668°W |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1972–1996 |

| Height | 6 ft 0 in (1.83 m)[1] |

| Spouses | Erroll Wetanson

(m. 1975; div. 1978)Bernard Faucher

(m. 1979; div. 1985) |

| Father | Jack Hemingway |

| Relatives | Mariel Hemingway (sister) Ernest Hemingway (paternal grandfather) Hadley Richardson (paternal grandmother) |

Margaux Louise Hemingway (born Margot Louise Hemingway; February 16, 1954 – July 1, 1996)[a] was an American fashion model and actress. The granddaughter of writer Ernest Hemingway, she gained independent fame as a supermodel in the 1970s, appearing on the covers of magazines including Cosmopolitan, Elle, Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, and Time. Her younger sister Mariel is a well-known Hollywood actress.

She signed a million-dollar contract with Fabergé Inc. as the spokesmodel for Babe perfume. Her later years were marred by highly publicized episodes of addiction and depression, before her suicide from a drug overdose on July 1, 1996, at the age of 42.

Early life

[edit]Margot Louise Hemingway was born February 16, 1954, in Portland, Oregon, the second of three daughters born to Byra Louise (née Whittlesey) and Jack Hemingway (eldest child of writer Ernest Hemingway). When she learned that she was named after the wine Château Margaux, which her parents drank on the night she was conceived, she changed the spelling from "Margot" to "Margaux" to match.[2] She had two sisters, actress Mariel Hemingway and Joan (nicknamed Muffet).

During her childhood, the family relocated from Oregon to Cuba, where her grandfather had lived,[2] then to San Francisco, and later to Idaho, where they lived on her grandfather's farm in Ketchum, adjacent to Sun Valley. The family took trips each summer back to Oregon with the daughters' godmother, who owned a farm in Salem.[5] She attended the Catlin Gabel School in Portland for her junior year.[6]

Margaux struggled with several disorders beginning in her teenage years, including alcoholism, depression, bulimia, and epilepsy. With her permission, a video recording was made of her therapy session related to her bulimia, and it was broadcast on television. She also had dyslexia. In the 1990s, Margaux reported that she had been sexually abused by her father as a child.[7][8] In 2013, her younger sister Mariel said in the documentary Running from Crazy that both Margaux and their older sister Muffet had been sexually abused by their father.[9]

Career

[edit]1972–1975: modeling

[edit]Hemingway was 6 feet (1.8 m) tall and had success as a model, including her million-dollar contract with Fabergé as the spokesmodel for Babe perfume in the 1970s.[10] This was the first million-dollar contract ever awarded to a fashion model.[1] She also appeared on the covers of Cosmopolitan, Elle, Harper's Bazaar, and Vogue, as well as on the June 16, 1975, cover of TIME, which dubbed her one of the "new beauties".[11] The September 1, 1975, cover issue of Vogue called Hemingway "New York's New Supermodel".[12]

During the height of her modeling career in the mid- to late 1970s, Hemingway was a regular attendee of New York City's exclusive discothèque Studio 54, often in the company of such celebrities as Halston, Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, Grace Jones, and Andy Warhol. At such social mixers, she began to use alcohol and drugs.[1]

1976–1996: film career

[edit]

Hemingway made her film debut in the Lamont Johnson-directed rape and revenge film Lipstick (1976), alongside her 14-year-old sister Mariel, and Anne Bancroft. In it, she plays a fashion model who is terrorized by a rapist. The film's violent depiction of rape led it to be labeled an exploitation film, though in later years it had success as a cult film.[13]

She followed this with a supporting role in the Italian horror film Killer Fish (1979), opposite Lee Majors and Karen Black. Her following project was the comedy They Call Me Bruce? in 1982. In 1984, Hemingway had a supporting part in Over the Brooklyn Bridge, opposite Elliott Gould and Shelley Winters. After a skiing accident in 1984, Hemingway gained 75 pounds (34 kg), ending up at nearly 200 lb (91 kg), and became increasingly depressed. In 1987, she checked into the Betty Ford Center.[14]

Attempting to make a comeback, she appeared on the cover of Playboy in May 1990, and asked the magazine to hire Selig as the creative director for her cover story. It was shot in Belize.[15] Despite her attempts, Hemingway's budding film career began to falter, and she took roles in several B-movies, including Killing Machine (1984) and Inner Sanctum (1991).[16]

Hemingway continued to support herself by appearing in a small number of direct-to-video films into the 1990s, autographing her nude photos from Playboy, and endorsing a psychic telephone hotline owned by her cousin, Adiel Hemingway. Shortly before her death, she was set to host the outdoor adventure series Wild Guide on the Discovery Channel.[8]

Personal life

[edit]

Hemingway's first marriage, to Errol Wetson (Wetanson), ended in divorce. They met when, at age 19, she accompanied her father to the Plaza Hotel in New York City on a business trip. Four months later she moved from Idaho to New York City to live with Wetson as a guest at mentor Zachary Selig's apartment at 12 East 72nd Street, which was owned by heiress Gloria Vanderbilt.[citation needed]

It was there that Selig made Hemingway's business and social introductions to his friends, such as Marian McEvoy, fashion editor at Women's Wear Daily; photographer Francesco Scavullo; fashion designer Halston; Vogue fashion editor Francis Stein; and Jon Revson, Selig's cousin. Revson, a scion of the Revson family that created Revlon cosmetics, declined Selig's offer for Hemingway to endorse Revlon, whereas later Fabergé signed her on with the largest salary of its day. Revson did come to visit both Selig and Hemingway (with the Hemingway family) in Ketchum to congratulate her after Hemingway's TIME magazine cover appeared in June 1975.[citation needed]

Marian McEvoy quickly interviewed Margaux at a party given by Selig, which resulted in Hemingway's Women's Wear Daily front- and back-page story that launched Hemingway into the fashion limelight.[17]

On New Year's Eve 1979, Hemingway married French filmmaker Bernard Faucher in Ketchum, and they lived in Paris for a year.[18] She divorced him in 1985 after six years.[15]

Hemingway had strained relationships with members of her family. She had a tense relationship with her mother, though they reconciled prior to Byra's death from cancer in 1988. She also competed with her younger sister Mariel, who received greater accolades for her acting. In the 1990s, Hemingway alleged that her father, Jack, had molested her as a child. Her father and stepmother, Angela, resented the allegations and stopped speaking to her. Angela told People magazine, "Jack and I did not talk to her for two years. She constantly lies. The whole family won't have anything to do with her. She's nothing but an angry woman."[8]

A 2013 television documentary film Running from Crazy, in which Margaux's sister Mariel speaks of the Hemingway family history of alcoholism, drug addiction, molestation, and suicide, contains clips filmed by Margaux.[19]

Death

[edit]

On July 1, 1996, Hemingway was found dead in her studio apartment in Santa Monica. Though her body was found reportedly badly decomposed,[20] the official autopsy and California death records list July 1 as her date of death.[a] She had taken an overdose of phenobarbital, according to the Los Angeles County coroner's toxicology report one month later,[21] although her family had difficulty accepting the fact of her suicide.[1]

Hemingway was interred at the Hemingway family plot at Ketchum Cemetery in Ketchum, Idaho.[22]

Mariel Hemingway's husband told People in 1996 that, "This [year] was the best I'd seen [Margaux] in years. She had gotten herself back together",[23] but in a December 2005 episode of Larry King Live, Mariel said she now accepted her sister's death as a suicide.[24]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Lipstick | Christine McCormick | |

| 1979 | Killer Fish | Gabrielle | Alternative title: Naked Sun |

| 1982 | They Call Me Bruce? | Karmen | |

| 1984 | Over the Brooklyn Bridge | Elizabeth Anderson | |

| 1984 | Killing Machine | Jacqueline | Alternative title: Goma-2 |

| 1987 | Portami la luna | Television movie | |

| 1991 | Inner Sanctum | Anna Rawlins | |

| 1992 | La donna di una sera | Ellen Foster | US title: Woman's Secret |

| 1992 | Bad Love | Jackie | |

| 1992 | Deadly Rivals | Agent Linda Howerton | Credited as Margot Hemingway |

| 1994 | Double Obsession | Heather Dwyer | Distributed by Columbia TriStar. Produced by Eduardo Montes-Bradley |

| 1994 | Inner Sanctum II | Anna Rawlins | |

| 1994 | Frame-Up II: The Cover-Up | Jean Searage | Alternative title: Deadly Conspiracy |

| 1995 | Vicious Kiss | Lisa | |

| 1995 | A comme acteur | ||

| 1996 | Dangerous Cargo | Julie | |

| 1996 | Backroads to Vegas | Television movie |

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Sources vary regarding Hemingway's birth and death dates. The New York Times, for example, erroneously lists her birthdate as February 19, 1955, in her obituary,[2] which conflicts with the official death record available from the state of California for a "Margot Louise Hemingway," which list her birthdate as February 16, 1954, born in the state of Oregon. Sources provide varying death dates for her as well, ranging from June 28, 1996[3] to June 29, 1996.[4] However, the official California death record lists July 1, 1996 (the date her body was discovered), as her date of death.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Estroff Marano, Hara (December 1, 1996). "What Killed Margaux Hemingway?". Psychology Today. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Holloway, Lynette (July 3, 1996). "Margaux Hemingway Is Dead; Model and Actress Was 41". The New York Times.

- ^ "Hemingway, Margaux". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022.

- ^ "Margaux Hemingway Biography". TV Guide. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022.

- ^ McInerny, Vivian (September 10, 2012). "Mariel Hemingway in Portland". Oregon Home Magazine. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Wohlfert, Lee (December 23, 1974). "Papa Hemingway's Granddaughter, Margaux, Is Fashion's Golden Girl". People. 2 (26). Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Irlen, Helen (1991). Reading by the Colors. Penguin. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-3995-3156-9. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Karen S. (July 15, 1996). "A Life Eclipsed". People. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Tapley, Kristophe. "Mariel Hemingway opens up about suicide, molestation and her family's curse in 'Running from Crazy'". HitFix. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Fonseca, Nicholas (June 29, 2001). "Papa's Little Girl". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Margaux Hemingway (cover)". TIME. June 16, 1975. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008.

- ^ "Margaux Hemingway (cover)". Vogue Timeline. No. September 1975. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- ^ Henderson, Eric (October 12, 2003). "Lipstick: Film Review". Slant Magazine. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Sloman, Tony (September 18, 2011). "Obituary: Margot Hemingway". The Independent. London.

- ^ a b Freytag, Arny (May 1990). "Margaux Hemingway: 'Papa's Girl' (Pictorial)". Playboy. Vol. 37, no. 5. pp. 126–35.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (December 1, 1994). "Video as Drive-in". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Margaux Hemingway". E! True Hollywood Story. Season 1. Episode 4. January 12, 1997.

- ^ "Once more, Margaux". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Associated Press. January 2, 1980. p. 2B.

- ^ Germain, David (January 22, 2013). "Mariel Hemingway runs from crazy at Sundance". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ Rainey (August 21, 1996). "Margaux Hemingway's Death Ruled a Suicide". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Coroner Says Death of Actress Was Suicide". The New York Times. August 21, 1996.

- ^ Holmes, Baxter (September 7, 2015). "Visiting Hemingway's Grave". Esquire. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Last Act". People. Vol. 46, no. 10. September 2, 1996. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ Presenter: Joan Rivers (December 22, 2005). "Surviving Suicide of Loved One". Larry King Live. CNN. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

External links

[edit]- 1954 births

- 1996 deaths

- 1996 suicides

- Hemingway family

- Actresses from Portland, Oregon

- American film actresses

- American female models

- Female models from Idaho

- Actresses from Idaho

- 20th-century American actresses

- Burials in Idaho

- Drug-related suicides in California

- Barbiturates-related deaths

- Female models from Oregon

- People with epilepsy

- Catlin Gabel School alumni

- Models who died by suicide