Robert Barton

Robert Barton | |

|---|---|

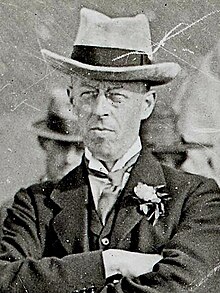

Barton in 1921 | |

| Minister for Economic Affairs | |

| In office 26 August 1921 – 9 January 1922 | |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Kevin O'Higgins |

| Director of Agriculture | |

| In office 2 April 1919 – 26 August 1921 | |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Art O'Connor |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office May 1921 – June 1923 | |

| Constituency | Kildare–Wicklow |

| In office December 1918 – May 1921 | |

| Constituency | Wicklow West |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Childers Barton 14 March 1881 Annamoe, County Wicklow, Ireland |

| Died | 10 August 1975 (aged 94) Annamoe, County Wicklow, Ireland |

| Political party | Sinn Féin |

| Spouse |

Rachel Warren

(m. 1951; died 1972) |

| Relatives | Erskine Childers (cousin) |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Occupation | Landowner |

Robert Childers Barton (14 March 1881 – 10 August 1975)[1] was an Anglo-Irish politician, Irish nationalist and farmer who participated in the negotiations leading up to the signature of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. His father was Charles William Barton and his mother was Agnes Alexandra Frances Childers. His wife was Rachel Warren of Boston, daughter of Fiske Warren. His double first cousin and close friend was Erskine Childers.[2]

Early life

[edit]He was born in County Wicklow into a wealthy Irish Protestant land-owning family; namely of Glendalough House.[2][3] Educated in England at Rugby and Oxford, he became an officer in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers on the outbreak of World War I.[4] He was stationed in Dublin during the 1916 Easter Rising and came into contact with many of its imprisoned leaders in the aftermath while on duty at Richmond Barracks.[5] He resigned his commission in protest at the heavy-handed British government suppression of the revolt. He then joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood.[6]

Family

[edit]Charles William Barton (father) was born on 13 July 1836. He married Agnes Alexandra Frances Childers, daughter of Rev. Canon Charles Childers, on 26 October 1876. He died on 3 October 1890, aged 54. Robert's two younger brothers, Erskine and Thomas, died in the British Army during World War I.[7]

Politics

[edit]At the 1918 general election to the British House of Commons Barton was elected as the Sinn Féin member for Wicklow West.[8] In common with all Sinn Féin members, he boycotted the Westminster parliament and sat instead in Dáil Éireann (the First Dáil). Arrested in February 1919 for sedition, he escaped from Mountjoy Prison on St. Patrick's Day (leaving a note to the governor explaining that, owing to the discomfort of his cell, the occupant felt compelled to leave, and requesting the governor to keep his luggage until he sent for it). He was appointed as Director of Agriculture in the Dáil Ministry in April 1919.[9] He was recaptured in January 1920 and sentenced to three years' imprisonment, but was released under the general amnesty of July 1921.

In May of that year, prior to his release, he was elected as a Sinn Féin member for Kildare–Wicklow in the 1921 Irish election to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland.[10] Once again all Sinn Féin members boycotted this parliament, sitting as the Second Dáil. In August 1921, he was appointed to cabinet as Secretary for Economic Affairs.[11]

Barton was one of the Irish plenipotentiaries to travel to London for the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations.[12][13] His cousin was a secretary to the delegation. Barton reluctantly signed the Treaty on 6 December 1921, defending it "as the lesser of two outrages forced upon me and between which I had to choose".

Although he had signed the Treaty and voted for it in the Dáil, he stood for election in June 1922 for Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin, the only TD who had voted for the Treaty to do so, and won a seat in the Third Dáil. In common with other Anti-Treaty TDs, he did not take his seat. In October 1922 he was appointed Minister for Economic Affairs in de Valera's "Emergency Government", a shadow government in opposition to the Provisional Government and later to the Executive Council of the Irish Free State. Barton's memoir of this period was completed in 1954, and can be seen on the Bureau of Military History website. He was arrested and interned for most of the war at the Curragh Camp.[14]

Barton was defeated at the 1923 general election,[10] and retired from politics in favour of the law. He practiced as a barrister, and later became a judge.[15] He was chairman of the Agricultural Credit Corporation from 1934 to 1954. Barton died at home in County Wicklow on 10 August 1975, at the age of 94, the last surviving signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Éamon de Valera died only nineteen days later, on 29 August 1975.

Interview

[edit]In 1969, RTÉ Television interviewed Barton, alongside Ernest Blythe and James Ryan, about the 1918 general election.[16][17]

Glendalough House

[edit]Glendalough House, run by Barton for over 70 years until his death, is still considered one of Ireland's most notable properties,[2][18][19] alongside nearby Powerscourt Estate. The house was the center of numerous political meetings and gatherings from 1910 to 1922.[20] It's also been featured as a location in many large Hollywood films including Excalibur,[21] Saving Private Ryan and Braveheart.[19][22]

Barton's grandfather Thomas Johnston Barton, who acquired Glendalough House in 1838, was a younger son of Hugh Barton, owner of the Langoa Barton and Léoville Barton vineyards in France and co-founder of the Bordeaux wine house of Barton & Guestier. The vineyards are now owned by Lilian Barton, a descendant of Hugh Barton’s eldest son, and she and her husband Michel Sartorius added Château Mauvesin Barton to these domaines in 2011.[23][24]

References

[edit]- ^ "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Barton Collection". Wicklow County Archives. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to Glendalough Estates". glendaloughestates.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2004.

- ^ Dempsey, Pauric J.; Boylan, Shaun. "Barton, Robert Childers". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Batt (1929). With Michael Collins in the fight for Irish independence. P. Davies, ltd. p. 60. ASIN B00086A93Y.

- ^ "Irish Appalled At Death of Collins; Fell Fighting with Victory at Hand; Dail Meets Soon to Seek New Leader; Ireland's Future in Doubt" (PDF). The New York Times. 24 August 1922. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Statement by Miss Dulcibella Barto" (PDF). bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie. 31 March 1954. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Robert Barton". Oireachtas Members Database. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "HEADS OF DEPARTMENT – Dáil Éireann (1st Dáil) – Wednesday, 2 April 1919". Houses of the Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Robert Barton". ElectionsIreland.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "THE NEW MINISTRY – Dáil Éireann (2nd Dáil) – Friday, 26 August 1921". Houses of the Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Stock Photography, Royalty-Free Photos & The Latest News Pictures - Getty Images". pro.corbis.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Stock Photography, Royalty-Free Photos & The Latest News Pictures - Getty Images". pro.corbis.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Statement by Witness - Document No. W.S. 979" (PDF). militaryarchives.ie. 27 July 1954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Neil (2015). According to their Lights. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9781848894952. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Standing For An Irish Parliament". RTÉ Archives. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Features". RTÉ News. 18 April 2006. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ Raineval, Melville Henry Massue marquis de Ruvigny et (1 January 1994). The Plantagenet Roll of the Blood Royal: Being a Complete Table of All the Descendants Now Living of Edward III, King of England. The Anne of Exeter volume. Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 9780806314334. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Glendalough court case dropped: ThePost.ie". Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Boyle, Andrew. "The Riddle of Erskine Childers" (Hutchinson) (1977) ISBN 0-09-128490-2. p.249

- ^ "Excalibur (1981)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2018 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "Wicklow Film Commission - Filming in Ireland". Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Sir Bernard Burke and A. C. Fox-Davies, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland, Harrison & Sons, London, 1912, pp. 31-32.[1]

- ^ “New Generation Leaders”, Wine Spectator, 31 March 2018.

- 1881 births

- 1975 deaths

- Politicians from County Wicklow

- Protestant Irish nationalists

- People educated at Rugby School

- Royal Dublin Fusiliers officers

- Early Sinn Féin TDs

- Members of the 1st Dáil

- Members of the 2nd Dáil

- Members of the 3rd Dáil

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wicklow constituencies (1801–1922)

- UK MPs 1918–1922

- Childers family

- 20th-century Irish judges

- British Army personnel of World War I

- People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side)

- The Irish Press people

- Ministers for agriculture of Ireland

- Lawyers from County Wicklow

- Military personnel from County Wicklow