Colonel Tom Parker

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

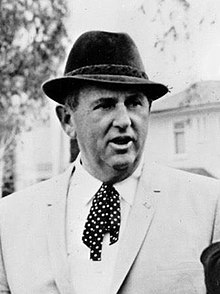

Tom Parker | |

|---|---|

Parker in 1969 | |

| Born | Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk June 26, 1909 Breda, Netherlands |

| Died | January 21, 1997 (aged 87) Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Occupation | Talent manager |

| Years active | 1938–1984 |

| Spouses |

|

| Awards | Honorary colonel (Louisiana) |

Thomas Andrew Parker (born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk; June 26, 1909 – January 21, 1997),[1] commonly known as Colonel Tom Parker, was a Dutch-American musical entrepreneur. He was best known as the talent manager of Elvis Presley.

Parker was born in the Netherlands and entered the United States illegally when he was 20 years old. He adopted a new name and claimed to have been born in the United States. With a background working in carnivals, Parker moved into music promotion in 1938, working with one of the first popular crooners, Gene Austin, and country music singers Eddy Arnold, Hank Snow, and Tommy Sands. He also assisted Jimmie Davis's campaign to become governor of Louisiana, for which he was awarded the honorary rank of "colonel" in the Louisiana State Guard.[2][3]

Parker encountered Presley in 1955 and by 1956 had become his manager. With Parker's help, Presley signed a recording contract with RCA Victor, which led to a commercial breakthrough in 1956 with his sixth single "Heartbreak Hotel" and a career as one of the most commercially successful entertainers in the world. Parker received more than half of the income from the enterprise, an unprecedented figure for a music manager. He negotiated Presley's lucrative merchandising deals and media appearances and is said to have influenced Presley's personal life, including his decision to accept military service in 1958 and his marriage to Priscilla Beaulieu in 1967. Parker encouraged Presley to make musical films, and they became the focus of his career during his commercial decline in the 1960s until his 1968 comeback and return to touring. Parker's influence waned in later years, but he continued in his management role until Presley died in 1977.

Parker managed the Presley estate for the rest of his life. Having previously sold the rights to Presley's early recordings to RCA he struggled to secure a steady income, and his financial situation worsened after he sustained significant gambling losses.[4][5] Parker's final years were spent living in Las Vegas, in declining health, until his death in 1997.[1]

Early life

[edit]Thomas Andrew Parker was born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk on June 26, 1909, in Breda, North Brabant, Netherlands.[4] He was the fourth of 11 children of Maria Elisabeth (Marie) Ponsie and Adam van Kuijk.[6] His Catholic father, a former military man of 12 years, was working as a deliveryman for catalogs when Parker was born. He died at the age of 59 when Parker was 16.

After his father's death, Parker moved to the port city of Rotterdam and lived with an aunt and uncle. His uncle was a skipper by profession who sailed from Breda to Rotterdam.[4] At the age of 17, Parker expressed a desire to run away to the United States to "make his fortune", and he entered the US illegally.

Biographies usually mention 1927 as the year of Parker's first attempt to emigrate to the US, but according to the Holland-Amerika Lijn passenger list that became available online in 2023, he was sent back from New York to the Netherlands on March 20, 1926. He returned home to Rotterdam on the steamship SS Veendam. The address he was registered at was Spanjaardstraat 110, Rotterdam. The entry in the passenger list shows the voyage was paid for by the US government. (The passenger lists can be viewed online at the Rotterdam archives.)[7]

In May 1929, aged nearly 20, Parker returned to the US, this time to stay. Having had previous experience in the traveling entertainment industry, he found work with carnivals and traveled with a Chautauqua educational tent show.[4] A few months later he enlisted in the United States Army, under a false identity to disguise his illegal entry into the country. His new name, Tom Parker, is said to have been taken from the officer who interviewed him during his enrolment. He completed basic training at Fort McPherson in Georgia.[4]

Parker served two years in the 64th Coast Artillery at Fort Shafter, Hawaii, and shortly afterward reenlisted at Fort Barrancas, Florida. Although he had served honorably for a time, he went AWOL in Florida and was charged with desertion. He was punished with solitary confinement, from which he emerged with a psychosis that led him to spend two months in a mental hospital.[4] His condition caused him to be discharged from the army.

Following his discharge, Parker worked at odd jobs, including short-term employments at food concessions and gaming carnivals.[4] Between 1931 and 1938, he worked with Royal American Shows,[8] and began building a list of contacts that would prove valuable in later years.[4]

In 1935, he married 27-year-old Marie Francis Mott. They struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression, working confidence tricks and traveling across the country in search of work.[9] Parker later said that at times they had to live on as little as $1 a week (US$22 in 2023 dollars).[10][9]

Career

[edit]Early talent management (1938–1954)

[edit]Parker first became involved in the music industry in 1938 as a promoter, working with popular crooner Gene Austin whose career was at a low point, despite having sold 86 million records since 1924 and earned over $17 million. Austin had spent much of his fortune on extravagant living and his popularity had been eclipsed by other singers such as Bing Crosby. Parker found his career transition smooth, and he used his carnival experience to sell tickets and attract crowds to Austin's concerts.[11] While he was a successful promoter, Parker now wanted to move into management.[11]

Austin offered Parker the opportunity to move to Nashville, Tennessee, where music was becoming big business, but Parker turned down the offer.[12] He decided to stay with his family in Temple Terrace, Florida, perhaps to avoid having to submit paperwork that could expose his illegal status.[12] Within a year, Parker had the opportunity to become a legal citizen of the United States when a new law allowed illegal aliens the chance to become US citizens, in return for a promise to fight for the country during World War II if required.[13] Parker served in the peacetime army, but never subsequently applied to become a US citizen,[13] possibly to prevent his previous army record from becoming public or to avoid having to fight.

He found employment as a field agent with a local animal shelter, the Hillsborough County Humane Society. The job offered him not only a secure wage, but also a rent-free apartment for him and his family in a remote part of West Tampa. With the society needing funds, Parker used his promotional experience to raise money and awareness.[13] As part of the fundraising, Parker went to Tennessee to find acts to perform at his charity events,[13] among them well-known artists such as Minnie Pearl and Eddy Arnold.[14] He became involved in music promotion again, but for himself rather than the society.[13] In 1945 Parker became Arnold's full-time manager, signed a contract for 25% of his earnings [14] and over the next few years helped him to secure hit songs, television appearances and live tours.[14]

In 1948, Parker was awarded the honorary rank of colonel in the Louisiana State Militia by Jimmie Davis, the governor of Louisiana and a former country singer, in gratitude for Parker's work on Davis's election campaign. The rank was honorary, since Louisiana had no organized militia, but Parker used the title throughout his life, becoming known simply as "the Colonel".[14]

A young singer, Tommy Sands, caught his eye in 1952, and Parker immediately began promoting him. He arranged live appearances and became a father figure to the then 15-year-old. Parker had intended to mold Sands into the next Roy Rogers, but Sands was not interested. Parker sent demonstration recordings of Sands to record producer Steve Sholes at RCA Victor, who offered to find songs for him to record.[15]

Eddy Arnold fired Parker in 1953 because of his growing involvement with singer Hank Snow,[14] but Parker remained involved in Arnold's live tours and demanded a buyout of $50,000 (US$569,403 in 2023 dollars[10]) to settle their contract.[14] Parker and Snow eventually formed Hank Snow Enterprises and Jamboree Attractions, a successful promotional outfit for up-and-coming country singers.[14]

Meeting Elvis Presley

[edit]In early 1955, Parker heard about Elvis Presley. Presley had a singing style different from the current trend, and Parker became interested in the future of this musical sound. At that time, Parker believed Presley to be black. At this time, Presley was singing in a trio called The Blue Moon Boys, with guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. Moore became Presley's first manager at the encouragement of Sun Records owner Sam Phillips, who was worried about unscrupulous promoters taking advantage of Presley. However, Moore and Black were excluded when Presley signed a recording contract with Phillips. Phillips told them to make a separate deal with Elvis. According to Moore, Presley agreed to take 50%, with Moore and Black splitting the other 50%. A one-year management contract with Presley gave Moore a 10% commission, which he never took. The contract, dated July 12, 1954, eight days after their first recording session, was signed by Presley and his parents. When the contract expired, the Memphis radio personality Bob Neal stepped in and made a deal with Phillips to become Presley's manager. By this point, Moore and Black had no contractual ties to either Phillips or Presley.[16]

Neal began to struggle to accommodate his new client's success, and in February 1955, following a meeting with Parker, Presley agreed to let Parker take some control of future bookings and promotions.[14]

Parker and Neal worked together to promote Presley, using their own Hank Snow Tour to book him and tour him.[14] Although Neal remained Presley's official manager, Parker became increasingly involved in managing his career. By the summer of 1955 he had become Presley's "special advisor".[14] As Presley was still a minor, his parents had to sign the contract with Parker on his behalf.[17][18] Part of Parker's role was to secure a new recording contract with a more prominent label.[14] Presley had been at Sun Records since the beginning of his career, but Sam Phillips, the owner of Presley's current label, was aware that to have any success in the future Presley would need the backing of a much larger brand.[14] Despite this, Phillips was not keen to let him go quickly, advising Parker that he would require $40,000 (US$454,957 in 2023 dollars[10]) to secure the release of Presley's contract, an utterly unheard-of sum at the time.[14]

Parker immediately began to seek a new label for Presley. Both Mercury Records and Columbia Records showed interest. However, their initial offers were nowhere near the $40,000 requirement. RCA Victor, Hank Snow's current label, also showed an interest, although it was somewhat wary of the cost of the contract. However, RCA Victor producer Steve Sholes was convinced that Presley's style of music would be a massive hit if he signed with the right label, and he began talks with Parker. RCA made clear that it was unwilling to go above $25,000 for a practically unknown singer, but Parker persuaded them that Presley was no ordinary unknown singer.[14] Around the same time, realizing the deal for Presley might fall through due to the cost of the contract, Parker attempted to sell Tommy Sands to RCA. He suggested to Sholes that Sands could record material similar to Presley's style. Remembering his previous experience with Sands, Sholes dismissed Sands as a viable replacement for Presley. [15]

In November, Parker and Snow persuaded RCA to buy Presley out from Sun for $40,000, and on November 21, Presley's contract was officially transferred from Sun Records to RCA Victor. Snow attended the signing, thinking Elvis had signed a management contract with Jamboree Attractions, which he owned with Parker. However, that was not the case since Elvis was still under contract with Bob Neal. The document signed on November 21 pertained to the record label transfer.[19] In return for a more significant financial stake in the deal, Neal agreed not to renew his management contract with Presley after it expired in March 1956,[20] allowing Parker the opportunity to claim the job for himself.

Signing Elvis (1956–1957)

[edit]On March 26, 1956, after Presley's management contract with Neal expired, Presley signed a contract making Parker his exclusive representative.[21] Later, when Hank Snow asked Parker about the status of their contract with Presley, Parker told him: "You don't have any contract with Elvis Presley. Elvis is signed exclusively to the Colonel."[22]

With his first RCA Victor single, "Heartbreak Hotel", in 1956,[23] Presley became a recording star, and Parker began bringing his new star to the national stage. He arranged for Presley to appear on popular television shows, such as The Milton Berle Show and The Ed Sullivan Show, securing fees that made Presley the highest-paid star on television.[24] By the summer, Presley had become one of the most famous new faces of the year, causing excitement among the new teenage audience and outrage among some older audiences and religious groups.[24] Presley said of Parker: "I don't think I would have ever been huge if it wasn't for him. He's a brilliant man."[25][26]

Parker signed a deal with Beverly Hills film merchandiser Hank Saperstein for nearly $40,000 to turn Presley into a brand name.[24] With over 78 different products for sale, from charm bracelets to record players, Presley merchandise brought in $22 million by the end of 1956.[24] Parker, with his 25% share of profits, found ways to make money from his artist that other managers had never thought of, such as simultaneously selling "I Love Elvis" and "I Hate Elvis" buttons.[24]

In April 1956, Parker made his first mistake with Presley's career. He booked Presley for a four-week engagement in Las Vegas, misjudging the potential reactions of the slightly older, more reserved audiences that Las Vegas attracted.[27] While Presley was a hit among the youth of America, older audiences found him an oddity.[27] Some viewed him as a clown-like figure, wiggling his hips for screams, while others found him vulgar and more suitable for late-night gentleman's clubs.[28] After a cold reception during his first few shows,[29] Parker cut Presley's appearance to two weeks. Presley remembered the event as one of the worst moments of his career.[27]

Despite this setback, Presley's career continued to grow. Remembering that Presley had expressed interest in acting when they first met, Parker arranged a screen test with Paramount Pictures. The company was impressed with Presley's acting ability, and they signed Presley to a seven-picture contract.[30] Parker ensured that the agreement allowed Presley the freedom to make at least one film a year with another studio and also managed to set up an office, with staff, at Paramount. Presley's acting career was initially intended to be a serious one. However, Parker persuaded Presley to sing in his movies after seeing the opportunity to cross-promote singles and albums with the films. This proved very lucrative, especially when the single for Presley's first film, Love Me Tender, sold over one million copies in advance sales. By the end of 1956, Parker had made Presley one of the world's most well-known and well-paid entertainers.[31]

In 1957, Parker finally managed to give Tommy Sands his big break by arranging for him to audition for and star in an episode of Kraft Television Theater called "The Singin' Idol". The episode's storyline was loosely based on the life and career of Presley.[32] NBC had originally wanted Presley for the role, but Parker had turned them down. In the drama, the role of Sands was portrayed as a "twisted psychopath". Critics were very positive in their reviews of both the drama and Sands, leading to Capitol Records signing Sands within a week. Soon after, Sands' song "Teen-Age Crush" reached number 2 on the pop charts, eventually selling 800,000 copies. [15]

Elvis in the Army (1958–1960)

[edit]Regardless of Parker and Presley's success, Parker was still struggling to believe that Presley's career would last longer than a year or two.[33] Parker had seen many acts come and go during his earlier years in management and felt that it would be foolish to believe that Presley, despite being Parker's most successful act to date, would be any different. In January 1958, Presley received his draft notice from the United States Army.[34] Presley was upset about the potential negative effect accepting the draft could have on his career, but Parker was secretly overjoyed.[33]

Presley had been showing signs of rebellion against Parker, and Parker believed that a stint in the Army would cure him of this. Parker was looking ahead when he persuaded Presley to become a soldier. Presley had wanted to join Special Services, allowing him the opportunity to perform while at the same time getting a more leisurely ride than other soldiers. Parker, on the other hand, was fully aware that any particular treatment given to Presley would instantly be used against him in the media and by those who disliked his style of music. If Presley could show the world that he was treated the same as any other young man, Parker told him, then more people would accept him and his music. Parker was also afraid that any attempt to block Presley from being drafted would result in a more detailed look into Parker's own service record. He also realized that it would be an excellent opportunity to promote Presley by having the media witness his induction day, including the army haircut that would see the shearing of Presley's iconic hairstyle.[33]

While Presley served in West Germany, Parker appeared to be in complete control, but he was worried about the outside influences that Presley might encounter there. Parker had declined to travel to Europe to visit Presley, denying that he spoke any language other than English. He sent Presley's friends to keep him company, arranged for business associates to watch over him while working in Europe, and maintained regular contact with him. He was reportedly afraid that Presley would realize that other managers were prepared to sign contracts that did not require as much as 25% of his earnings.[35]

Parker also worried about Presley losing his fame while he was away in the army, so Parker worked hard to keep Presley's name known to the public. He realized that by keeping RCA Victor and the public hungry for more Presley material, he could negotiate a better contract when Presley returned from active service.[33] He had arranged for Presley to record five singles before his induction,[35] guaranteeing RCA Victor enough material to release over two years. RCA was eager for Presley to record in West Germany. Still, Parker insisted it would ruin his reputation as a regular soldier if he could go into a recording studio. Stories appeared in the press regularly about Presley, including that he would do a live CCTV broadcast when he returned and that he had signed a deal for a series of annual television spectaculars to be broadcast across the country.[35] All of these stories were fabrications, but they kept Presley's name in the public consciousness.

Elvis returns (1960–1965)

[edit]For Presley's return in March 1960, Parker arranged for a train to take him from Washington, D.C., to Memphis, with stops so that fans could see their idol in person.[36] If Parker was still worried about Presley's having lost his fame, he was disabused of this notion when he witnessed the turnout along the route.[37]

Frank Sinatra, who had declared Presley a rock and roll disgrace in the 1950s, had since become keen to have him appear on The Frank Sinatra Show.[38] Parker, not one to forget harsh criticism, stated that the fee would be $125,000 (equivalent to about $1,287,000 in 2023) for two songs, a total of eight minutes on screen; Sinatra himself was receiving a lower sum for the whole show,[39] but he agreed. The show, "Welcome Home, Elvis", was Presley's first national television appearance since The Ed Sullivan Show in January 1957.

After the Sinatra special, Parker decided that Presley's future lay in Hollywood.[38] He envisioned Presley as an entertainment machine on becoming a film actor, pumping out three feature films and soundtracks a year until the decade's end.[38] He allowed him to perform three live shows in 1961, all charity events, two in Memphis and one in Hawaii.[38] After that, Presley gave no live performances until 1968 and had minimal contact with his fans.[38] Parker signed long-term contracts with the Hollywood film studios,[40] possibly to guarantee work and income for both him and Presley. This was, in hindsight, a mistake on his part; if he had negotiated each deal separately based on the profits of the previous film, he could have received more money.[40] Throughout the 1960s, Parker continually renegotiated Presley's film contracts, often paying little attention to his client's scripts or concerns.[41] These deals were sometimes so harsh on the studios that it led producer Hal Wallis to state: "I'd rather try and close a deal with the Devil."[41]

Presley had to do no more than provide RCA Victor with three albums a year,[38] and his film soundtracks did that for him. With no concert touring or public appearances to be made, Parker was able to keep costs to a minimum.[38] For the first few years, Presley's films were somewhat successful, his albums topped the charts, and any singles released were mainly hits. But as time went on, Presley became less significant as the Beatles began to dominate the music charts, and the worldwide phenomenon known as Beatlemania began. Presley's films still made money, and his albums still sold well, but the profits were falling. This led Parker to insist that films be made cheaply, on a strict schedule, and with as little hassle as possible. [40]

Dead ends (1966–1967)

[edit]For the remainder of the 1960s, Presley starred in films that relied heavily on exotic locations and mundane songs, and he was tied into contracts that he could not escape. Parker did not appear to care if the films were good or bad, but only about the profits.[40] When Presley complained to him that he wanted better scripts, Parker reminded him of his lavish lifestyle and that risking $1 million a year for doing practically no work was dangerous. Presley's career stagnated while artists like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and The Beach Boys dominated the charts. Later, in a 1983 interview, Parker admitted that after 1966, the income from Presley films and soundtracks had dramatically declined. [42]

To make up for the lack of earnings, Parker arranged for Presley's gold Cadillac to go on tour.[42] Selling it to RCA for $24,000 ($225,378 in 2023 dollars[10]), it was used to promote Presley's latest film, Frankie & Johnny.[42] The Cadillac tour proved somewhat more successful than the film itself.[42] In Houston alone in one afternoon, 40,000 people paid to see it, with one woman offering to have sex with the tour manager if he would allow her to sit in it.[42]

On January 2, 1967, Parker re-negotiated his managerial/agent contract with Presley, persuading him to increase Parker's share from 25% to 50% on certain transactions. When critics questioned this arrangement and wondered if Parker was taking advantage of Presley, Presley quipped, "I could have signed with East Coast Entertainment where they take 70%!"[43] Parker used the argument that Presley was his only client and he was thus earning only one fee.[43] In 1966, with Presley showing signs of rebellion again, and his career on the decline, Parker decided it was time for a new approach: marriage.[42] Presley had lived with Priscilla Beaulieu for the past four years, and Parker hoped that marriage would boost Presley's career and possibly tame him.[42] With Priscilla's stepfather dropping heavy hints, Parker persuaded Presley that he ought to make an "honest woman" of her very soon. Parker decided that Las Vegas was the perfect place to have the wedding,[42] and on May 1, 1967, the couple was married in a quiet ceremony that lasted only eight minutes and had a handful of guests.[44] A breakfast reception was arranged after the media got photographs of the couple.[44]

Live performance comeback (1968–1972)

[edit]

It took the 1968 television special Elvis, which was sponsored by Singer sewing machines, and a subsequent series of recording sessions in Memphis, Tennessee, that included songs such as "Suspicious Minds" and "In the Ghetto", to restore Presley's musical reputation. Steve Binder, the producer of the television special, put forward the idea of Presley singing his old hits. Binder also thought of the idea of Presley performing the staged section with his old band, Scotty Moore and D. J. Fontana; this had been inspired by a post-rehearsal informal jam in Presley's dressing room. Presley did not usually stand up against Parker, but he knew that this TV show was his one chance at a proper comeback, and with Binder backing him, Presley told Parker he was doing it "Binder's way". Their instincts were proven right; the TV special proved to be an enormous hit, and the released album featuring performances from the special became a best-seller. After the special, Parker managed Presley's return to live performance, including brief U.S. tours and many engagements in Las Vegas. Following the success of Presley's Las Vegas return, Parker signed a contract with the International Hotel to guarantee Presley would play a month-long engagement for $125,000 a week ($1,095,215 in 2023 dollars[10]), an unheard-of sum at the time. During this part of Presley's career, Parker and Presley agreed to a 50/50 "partnership", which, with Parker controlling merchandising and other non-music related items, resulted in Parker earning more than his client.[45]

After the success of Presley's return to live performing in Las Vegas, Parker decided it was time for Presley to go on tour for first time in 13 years.[46] The tours were so financially successful that they determined Presley's workload for the remainder of his life and career. Parker's main role during these tours was planning the logistics and ensuring tickets were sold.[46] He usually flew ahead to the venues and took charge of preparing everything for Presley's entourage ahead of their arrival. As a result, he and Presley rarely saw each other, and, as time progressed, it became even more difficult for Parker to get in contact with Presley.[46] These live performances, along with being financially lucrative, also allowed Parker to fulfill Presley's recording contract with RCA Victor. Between 1969 and 1972 alone, RCA released three albums of live material.[47]

By 1972, Parker had managed to increase Presley's weekly wage in Las Vegas to $150,000 ($1,092,601 in 2023 dollars[10]) and secured $50,000 a year ($364,200 in 2023 dollars[10]) for himself as a "consultant to the hotel chain".[48] Parker also decided that it was time for Presley to return to New York and arranged for him to perform at Madison Square Garden in June.[48] Originally planned as three performances, demand was so high that Parker decided to add a fourth performance, making Presley the first performer to sell out the venue four consecutive times. These four shows alone grossed $730,000 ($5,317,327 in 2023 dollars[10]).[48]

On July 8, 1972, inspired by the visit of President Richard Nixon to China a few months earlier,[49] Parker announced that there would be a worldwide satellite broadcast from Hawaii to allow the whole world the chance to see a Presley concert, "since we can't play in every major city".[50] Except for a few concerts in Canada in 1957, Presley never performed outside the United States. Parker held another press conference in Las Vegas on September 4, 1972, to confirm that the concert, now titled Aloha from Hawaii, would be broadcast on January 14, 1973.[50] The press was told that an audience of one billion was expected to tune in to see the "first entertainment special to be broadcast live around the world";[50] although Parker had not taken into account the fact that many countries, including parts of Europe and America, would not see the concert live due to the time of the broadcast.[50] Parker received a letter from Honolulu Advertiser columnist Eddie Sherman two weeks after the Las Vegas press conference.[51] Sherman had read in news accounts that there was to be no charge for admittance to the concerts, a donation to charity is required instead. He suggested to Parker that, as Presley had recorded and was still performing the song "I'll Remember You" written by Kui Lee, the donations could go to the Kui Lee Cancer Fund that had been set up following the death of the songwriter in 1966.[51] Seeing the chance to publicize Presley's charitable nature once again, Parker eagerly agreed.[51] The album was released simultaneously around the world and went to number 1 on the US charts in 1974, the first Presley album to do so since the Roustabout soundtrack.[50]

1973–1974

[edit]In May 1973, in an attempt to deal with Presley's growing dependence on prescription drugs, Parker and Presley's father, Vernon, attempted to cut off his drug supply.[52] They hired private detectives to find out where the drugs were coming from and successfully stopped any more from reaching Presley.[52] However, Presley found other doctors to meet his demands.[52] In later years, several of Presley's inner circles would tell of how difficult it was to persuade Presley to quit the drugs.[52] As well as being their employer and paying their wages, he was also their main source of drug access for themselves.[52] Presley's main doctor, George C. Nichopoulos, often replaced Presley's medication with placebos in an attempt to wean him off the drugs.[52] This trick would be successful for a short time, but when Presley discovered the trick, he found himself other doctors.[52] Author Alanna Nash suggests the possibility that Parker didn't intervene more because he may not have known how to handle the situation.[53] In Nash's book, The Colonel, she writes: "In the days before the Betty Ford Clinic, the Colonel didn't know where to take him for discreet, effective help and loathed risking the loss of work if the truth got out".[53]

After the Aloha special, Parker made a deal that would later be used in court to prove that he had not acted in Presley's best interests. He offered RCA Records the opportunity to buy Presley's entire back catalog for $5.4 million. At the time, the catalog was not considered very important, and RCA initially calculated it at being worth much less; however, in later years, it would become one of the most valuable record catalogs in the music business. The sale of the back catalog to RCA meant that after his death, Presley's estate would not receive any royalties for any Presley recordings made prior to 1973. However, Presley had asked Parker to raise funds to pay for his upcoming divorce settlement, as Priscilla filed for divorce in 1973.[46]

During a closing night performance on September 3, 1973, following news that a Hilton staff member of whom Presley was fond had been fired, Presley attacked Hilton Hotels chairman Barron Hilton in a verbal rage on stage. Parker was furious, and he stormed into Presley's dressing room after the show to confront him. After a heated argument between the two, Presley told Parker he was fired. Angered by this outburst, Parker declared: "You can't fire me. I quit!"

Parker accepted that their working relationship was over and demanded that Presley pay him $2 million to end their contract, money that Parker claimed he was owed. After nearly two weeks of trading insults back and forth, Parker and Presley decided to continue to work together.[54]

Although many around Presley were worried about his worsening drug dependency, Parker appeared to ignore the problem. Several members of Presley's band later stated that Parker had no idea just how bad the situation was getting. However, other friends and members of Presley's entourage have stood by the suggestion that Parker didn't want to admit there was such a problem because he didn't know how to deal with it, and he was also worried about any negative publicity it would create. According to Parker himself, he did privately attempt to talk to his client a number of times about the matter, but allegedly every time Parker casually told Presley to quit or at least tone it down with the pill popping and binge eating, Presley responded by telling Parker to stay out of his personal business.

From 1974 onward, Presley's weight gain and prescription drug abuse became too much to be controlled. In Las Vegas, he was starting to appear drugged on stage, slurring his words and forgetting song lyrics.[54]

1974–1977

[edit]In February 1974, during his engagement in Las Vegas, Presley, along with Parker, met with Barbra Streisand and Jon Peters.[55] They discussed the possibility of Presley co-starring with Streisand in a remake of the film A Star Is Born.[55] Seeing it as a chance to finally be taken seriously as an actor, Presley agreed to take the role if the contracts could be worked out. According to Presley's friend, Jerry Schilling, Presley was excited about the opportunity to take on a new challenge.[55] Streisand's production company, First Artists, offered Presley a salary of $500,000 ($2,831,169 in 2023 dollars[10]) and 10% of the profits.[55] Parker, who had always dealt with Presley's film contracts and viewed the offer as a starting bid to earning more money, instead asked for a salary of $1 million ($5,662,338 in 2023 dollars[10]), 50% of the profits, plus another $100,000 ($566,234 in 2023 dollars[10]) for expenses and spoke of needing to arrange details of a soundtrack deal.[55] First Artists, not used to such huge demands, didn't put forward a counteroffer and decided instead to offer the role, along with the original salary offer, to Kris Kristofferson, who accepted.[55] Parker later claimed that Presley had asked him to make the contract so demanding so that they would not offer him the part, although many of Presley's friends have contradicted Parker's statement because they had said Presley was furious at losing the role.[55]

Later in 1975, the government of Saudi Arabia offered Parker $5 million for Presley to perform there.[55] Parker turned the offer down, and Presley was overjoyed when they replied with another offer of $10 million.[55] Yet, despite Presley's eagerness to do the shows, Parker again turned them down.[55] Promoters in South America also made offers, as much as $2.5 million, and all of them were turned down by Parker; "Well, whenever I need $2.5 million, I'll call you," he once said to them.[55] Presley was beginning to consider new management, with Concerts West co-founder Tom Hulett being the clear favorite for the job.[55] Hulett's company had managed tours for Presley and had worked with artists such as Led Zeppelin. According to several people who knew Presley at the time, the talks with Hulett got so far along that it seemed almost inevitable that they would close the deal. The talks had included details about European tours, and buying out Presley's contract would not have been a problem for Hulett and his company.[55] Despite this, however, the deal never materialized. According to Presley's biographer Peter Guralnick, Presley and Parker "were really like, in a sense, a married couple, who started out with great love, loyalty, respect that lasted for a considerable period of time, and went through a number of stages until, towards the end of Presley's life, they should have walked away. None of the rules of the relationship was operative any longer, yet neither had the courage to walk away, for a variety of reasons." In any case, Parker remained Presley's manager without a break until Presley's death in 1977.

By this time, Parker was aware that Presley needed a rest from touring and the chance to deal with his prescription drug addictions. He phoned Presley's father once to suggest taking time off, but Vernon Presley told him they couldn't afford to stop touring due to Presley's constant and lavish spending. Vernon also threatened to find a new manager if Parker wouldn't continue to tour Presley.[56]

In July 1976, three of Presley's personal bodyguards and members of the "Memphis Mafia", Robert Gene "Red" West, his cousin Sonny West and David Hebler, were fired by Vernon Presley and decided to write a tell-all book about their life in his inner circle, Elvis: What Happened?.[57] Worried about the impact such details might have on his career, Presley, through his father, asked Parker to stop the publication. Parker made several attempts but failed to do so.[57] According to Presley's friend Larry Geller, Parker secretly wanted the book to be published, hoping that it would help Presley realize the severity of his situation and persuade him to do something about it.[57] The book was published one year later on July 12, 1977, about a month before Presley's death.[58]

For the remainder of Presley's life, Parker saw little of him. The two had become almost strangers, and false reports in the media suggested that Presley's contract was up for sale.[57] Although Parker publicly denied these claims, he had been in talks with Peter Grant, the manager of Led Zeppelin, about the possibility of him overseeing a European tour for Presley.[57] Despite the new rumors of Presley touring overseas, however, Parker never followed through with the deal.

1977: Presley's death

[edit]When Presley died on August 16, 1977, one day before he was due to go on tour, some accounts suggest Parker acted as if nothing had happened.[59] Other accounts suggest he slumped in his chair at his office, muttered, "Oh, dear God", and then quickly phoned Vernon Presley, where Parker advised Presley's father that his son's image needed to be protected. This would be more in keeping with Parker's own interests.[60]

Parker set out to protect his future income. When he was asked by a journalist what he would do now with Elvis Presley having passed away, Parker responded: "Why, I'll just go right on managing him!"[59] Almost immediately, before even visiting Graceland, Parker traveled to New York City to meet with merchandising associates and executives with RCA Records, instructing them to prepare for a huge demand in Elvis Presley products.[59] Shortly afterward, he traveled to Memphis for Presley's funeral. Mourners recall being surprised at his wearing a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap, smoking his trademark cigar, and purposely avoiding the casket.[59] At the funeral, he persuaded Presley's father to sign over control of Presley's career in death to him.[59]

In September 1978, shortly after the first anniversary of Presley's death, Parker arranged a fan festival, called Always Elvis, where he, Vernon, and Presley's ex-wife Priscilla dedicated a bronze statue of him in the lobby of the Las Vegas Hilton.[61]

1978–1997: After Elvis

[edit]Following Presley's death, Parker set up a licensing operation with Factors Etc. Inc, to control Presley merchandise and keep a steady income supporting his estate.[4] It was later revealed that Presley owned 22% of the company, Parker owned 56%, and the final 22% was made up of various business associates.[62] Due to an ill-advised agreement between Parker and Presley that gave RCA sole ownership of all his recording royalties prior to 1973, the estate was relying heavily on the income from Factors Etc.[4] However, because Parker was still entitled to 50% of all Presley's income, and after taxes were taken off, the overall amount going towards the upkeep of the estate was less than $1 million a year.[4]

In January 1979, it was discovered that Presley had lost out on royalties for songs on which he had been listed as an author or composer because Parker had unwisely advised him not to sign up with ASCAP or its younger competitor, BMI.[62] Experts in the field at the time estimated that this mistake had potentially cost Presley millions of dollars,[62] and it had potentially cost Parker millions too. Parker had unknowingly backed himself into a financial corner.

By 1980, the cost of running the estate was estimated to be as much as $500,000 a year.[4] Priscilla and the two other co trustees were prepared to let Parker continue to handle Presley's business affairs, and petitioned the court to that end.[5] However, Judge Joseph Evans, aware that Lisa Marie Presley was still a minor, appointed attorney Blanchard E. Tual to investigate Parker's management.[4][5] Tual, once appointed as Lisa Marie's guardian ad litem, chose to investigate the entire period of Parker's management of Presley; his preliminary finding was that Parker's management deal of 50% was extortionate compared to the industry average of 15–20%.[4] He also noted that Parker's handling of Presley's business affairs during his lifetime, including the decision to sell off past royalties to RCA for $5.4 million in 1973, was unethical and poorly handled.[5] During a second, more detailed investigation, Tual discovered that all earnings were paid directly to the trust instead of Parker.[4] By this time, with the IRS demanding almost $15 million in taxes, the estate was facing bankruptcy.[4]

On August 14, 1981, Judge Evans ordered Elvis Presley Enterprises to sue Parker for mismanagement.[5] Parker countersued.[5] The case against Parker was settled out of court in 1983, with the estate paying him $2 million ($6,118,276 in 2023 dollars[10])[5] in exchange for all Presley audio recordings or visual images that he owned[4] and the termination of his involvement in any Presley related earnings for five years.[4]

Parker worked as a "consultant" for Hilton Hotels for a number of years after Presley's death,[63] with some believing he was working to pay off debts owed to the casino from his gambling during Presley's performances there.[63] Part of this role resulted in Parker keeping the same fourth-floor suite he occupied when Presley was alive. By 1984, with his gambling debts reportedly rising again, he was evicted.[63] On the surface, however, relations between Parker and Hilton Hotels appeared to be as good as ever, with Parker helping the Hilton to organize another fan convention event in August 1987 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Presley's death.[63]

The disputes with the Presley estate did not terminate Parker's association with Presley. Parker appeared at posthumous events honoring Presley, such as the 1993 issuing of a U.S. postage stamp with Presley's likeness. He also became friendly with the estate again, attending special ceremonies and events in Memphis, invited by Priscilla.[63] However, he did occasionally bother them by criticizing some decisions. In 1994, following the marriage of Lisa Marie Presley and Michael Jackson, Parker stated that Presley would probably not have approved.[63] In 1993, during an event honoring Elvis Presley at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas, when a reporter questioned Parker's interest in Presley's enduring legend by quoting that interest that is sometimes notable for its obsessiveness, provoked Parker to remark: "I don't think I exploited Elvis as much as he's being exploited today."[63]

Personal life

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

As Presley's fame grew, the public became interested in Parker as well. For some time, Parker lied about his childhood, claiming that he was born in Huntington, West Virginia in the early 1900s—attempting to pass off his Dutch accent as a Southern accent. He claimed he had run away from home at an early age to join a circus owned by an uncle, then served in the U.S. Army prior to his involvement as a music manager. The truth about his early years was revealed in 1960 when one of Parker's sisters, Nel Dankers-van Kuijk, living in the Netherlands, recognized him in photographs standing next to Presley.[64]

One of Parker's brothers, Adam "Ad" van Kuijk, visited him once in Los Angeles in April 1961. Parker privately acknowledged his brother and even introduced him to Presley. During the week-long visit, Parker was informed by Adam that their mother had died three years earlier in 1958, never knowing what happened to her son. Adam van Kuijk died from emphysema in 1992, never seeing or visiting Parker again.[65]

The claim of Parker's Dutch heritage was publicly confirmed when Parker failed to avert a lawsuit brought against him in 1982 by asserting in open court that he was a Dutch citizen. The opposing counsel responded by presenting into evidence a copy of Parker's U.S. Army enlistment form which stated, through a legal loophole, that because Parker signed his enlistment papers under his alias "Thomas Andrew Parker" and swore allegiance to the United States, that he had renounced his Dutch citizenship.[66][a] In 1993, in one of Parker's last media appearances, he was interviewed by Dutch TV director Jorrit van der Kooi. The two spoke in Dutch about the Netherlands and about Elvis Presley's life and career, and Parker said he was not aware that another of his sisters, Adriana van Kuijk, had died in the Netherlands a few years earlier.

Marriage

[edit]In 1935, while traveling with a circus, Parker met and married a 27-year-old woman named Marie Francis Mott.[69] Marie was one of six children, had been married twice before and had a son from her first marriage.[69] Unbeknownst to Parker, she had a second son from her first marriage but had given him up for adoption at birth due to his disability, a club foot.[70] Some suggested that Parker married Marie to disguise his illegal status in the United States; a marriage to a U.S. citizen with a child could help him bury his past in a "ready-made family". There is no proof that anything other than romance led to their marriage.[69]

Others had doubts about whether they were legally married.[71] According to interviews given by Parker to the Associated Press many years later, he and Marie were married in Tampa, Florida during the winter of 1932, but the Florida Office of Vital Statistics has no record of such a marriage between a couple with those names at any time between 1927 and 1946. It is also recorded that Marie did not divorce her second husband until 1936, and her brother Bitsy recalled no ceremony of marriage between Parker and Marie. Author Alanna Nash has suggested that the couple may have simply placed their hands on a Bible and given themselves a "carny wedding".[71]

In the early days of their marriage, Marie and Parker worked together in the carnivals.[71] As Parker's management career began to take off, Marie became more of a housewife, although she would occasionally travel with him to various parts of the country. During the 1960s, after many years of ill health, Marie began to display signs of dementia. Parker began to distance himself emotionally from her, heartbroken by her slow mental deterioration from the woman he once knew.[72] Marie died on November 25, 1986, of a chronic brain syndrome at age 78.[73] In October 1990, Parker married Loanne Miller, his personal secretary since 1972.[72] He continued living in Las Vegas, mostly avoiding contact with the press.

Gambling

[edit]Many Parker biographers, including Dirk Vellenga and Alanna Nash, have stated that Parker's gambling habit began to get out of control in the mid-1960s. During the 1960s, with his wife's health deteriorating and Presley's career struggling, Parker found an escape in gambling at Las Vegas casinos. Fans and biographers alike believe that one of the main reasons Parker signed Presley to a Vegas hotel in 1969 for his live comeback was to help cover losses at their casino. He would often spend 12–14 hours at a time gambling in the casinos, betting large sums. It is believed that Parker lost at least $1 million a year from gambling. At the time of Presley's death in 1977, it was suspected that Parker owed the Las Vegas Hilton over $30 million ($150,840,198 in 2023 dollars[10]) in gambling losses. After a lifetime that saw him earn in excess of $100 million,[74] Parker's estate was worth barely $1 million when he died.[4]

"Colonel Tom Parker rubbed my head in Vegas", Eddie Murphy stated in 1989. "A couple times he set me up in the Elvis Presley suite on top of the Hilton, and I would go play Elvis for a week… One night we were at the crap table together and he rubbed my head for luck. I wanted to punch him in the face. But this guy is like eighty years old – too old to be taught the limits of racism… He probably doesn't realize how horrible a thing that was to do."[75]

Songwriter Mac Davis recounted a similar experience where Parker rubbed his head and declared "You're going to be a star. You tell everybody the Colonel touched your head." Later, Davis says "He remembered me, and he said 'I told you you were going to be a star.' I said, 'Yeah, you rubbed my head.' He said 'Did I really?' I said 'Yeah'. He said 'Well then there ain't no doubt about it. You're going to be a star.'"[76]

Death

[edit]Parker made his last public appearances in 1994.[77] By that time he was so stricken with diabetes, gout, and other health problems that he could barely leave his home.

On January 20, 1997, his wife heard a crash from the living room. When Parker failed to answer her calls, she went in to find him slumped in his armchair, having suffered a stroke. He died of complications from the stroke[77] the following morning at a hospital in Las Vegas, Nevada, at age 87, with his wife at his bedside. On his death certificate, in addition to his name, dates of birth and death, and the cause of death, it also lists his birth name as Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk, his place of birth as the Netherlands, and his citizenship (incorrectly) as American.[77]

His funeral was held a few days later at the Hilton Hotel and was attended by a handful of friends and former associates, including Eddy Arnold and Sam Phillips.[77] Priscilla Presley attended the funeral to represent the Elvis Presley Estate and gave a eulogy that, to many in the room, summed up Parker: "Elvis and the Colonel made history together, and the world is richer, better and far more interesting because of their collaboration. And now I need to locate my wallet, because I noticed there was no ticket booth on the way in here, but I'm sure that the Colonel must have arranged for some toll on the way out."[77] She reiterated her positive opinion to Tom Hanks in 2022 when the actor prepared to play Parker for Elvis (2022). Hanks said, "I was anticipating hearing horror stories about this venal, cheap crook. Just the opposite. Both Priscilla and Jerry said he was a lovely man". According to Priscilla, Elvis was happy to pay Parker 50% of his earnings to manage him.[78]

Portrayals and popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]Parker has been portrayed by:

- Pat Hingle in Elvis (1979), the original made-for-television film, produced by Dick Clark, directed by John Carpenter, and starring Kurt Russell.

- Hugh Gillin in the TV film Elvis and Me (1988).

- Beau Bridges in the TV film Elvis and the Colonel: The Untold Story (1993), alongside Rob Youngblood.

- Randy Quaid in the CBS miniseries Elvis (2005), alongside Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Elvis Presley. Quaid was nominated for a Golden Globe, Emmy Award and a Satellite Award win for Best Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie.

- John Carroll Lynch in the film Shangri-La Suite (2016)

- Billy Gardell in the CMT TV series Sun Records (2017). In this series Parker's connections with former clients Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow are also depicted along with his management of Presley.

- Tom Hanks in Elvis, the 2022 film about Presley, directed by Baz Luhrmann. He is shown to speak Polari, or “Palare” in this film, which is accurate[according to whom?] since carnival workers spoke Palare.[citation needed]

Literature

[edit]- Vivek Tiwary's The Fifth Beatle (2013), a graphic novel biography of the Beatles manager Brian Epstein, depicts a meeting between Parker and Epstein that took place in the mid-1960s. In the scene, Parker is satirically portrayed as a gluttonous, satanic figure. The scene contrasts Parker's management of Elvis with the freedom Epstein allows the Beatles. The scene also portrays Parker as antisemitic. Tiwary claimed in an interview that Parker did make those comments.[79]

Television

[edit]- In the TV series Vinyl, Richie Finestra (portrayed by Bobby Cannavale), president of record label American Century, meets Elvis Presley (portrayed by Shawn Klush) in 1973, in Las Vegas. Richie attempts to convince Elvis to stop singing in Las Vegas and instead focus on making new, creative music, acting like a true king. The Colonel (portrayed by Gene Jones) gets furious when he finds out Richie was going behind his back and talking about papers with Elvis and has Elvis point a gun at him.[80]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Strauss, Neil (January 22, 1997). "Tom Parker Is Dead at 87; Controlled Presley's Career". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (June 8, 2001). "Colonel of Lies". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Dash, Mike (February 24, 2012). "Colonel Parker Managed Elvis' Career, but Was He a Killer on the Lam?". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Victor, Adam (2008). The Elvis Encyclopedia. Gerald Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3816-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gaar, Gillian G. (2010). Return of The King: Elvis Presley's Great Comeback. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-28-2.

- ^ Nash, Alanna (July 13, 2010). The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451613575.

- ^ @StadsarchiefRotterdam. "English". Stadsarchief Rotterdam (in Dutch). Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Dickerson, James L. (2003). Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager. Cooper Square Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 058538827X.

- ^ a b Nash 2002, pp. 75–78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Nash 2002, pp. 79–82.

- ^ a b Vellenga 1990, pp. 54–60.

- ^ a b c d e Nash 2002, pp. 82–90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Victor, Adam (2008). The Elvis Encyclopedia. Gerald Duckworth. pp. 384–395. ISBN 978-0-7156-3816-3.

- ^ a b c Nash 2002, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Moore, Scotty; Dickerson, James L. (1997). That's Alright, Elvis: The Untold Story of Elvis's First Guitarist and Manager. Schirmer Books, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780028650302.

- ^ Vellenga 1990, pp. 85–90.

- ^ This deed on the part of Vernon and Gladys Presley marked a permanent separation of Elvis from his mother, and as Elvis was a classic "mama's boy". It was this, rather than his entrance into the Army or the later death of Gladys, from which Presley never truly recovered and which ultimately killed him.

- ^ Dickerson, James L. (2001). Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager. Cooper Square Press. p. 72.

- ^ Doll 2009, pp. 65–70.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter (1994). "Last Train to Memphis". Little, Brown. p. 258.

- ^ Dickerson, James L. Colonel Tom Parker, p. 73.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 7, track 3.

- ^ a b c d e Nash 2002, pp. 118–134.

- ^ Osborne. Elvis: Word for Word. p. 15.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter (1995). Last Train to Memphis: Rise of Elvis Presley. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10651-9.

- ^ a b c Guralnick 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Bulik, Mark (June 10, 2014). "1956: Elvis Is Introduced to the Nation". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 7, track 4.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 67.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 94.

- ^ "THE SINGIN' IDOL DVD - 1957 KRAFT TV Play BASED on ELVIS' STORY". www.thevideobeat.com. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Vellenga 1990, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Vellenga 1990, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 149.

- ^ Long, Trish. "1960: Elvis Presley fans welcome King of Rock 'n' Roll at Union Depot". El Paso Times. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vellenga 1990, pp. 112–115.

- ^ Guralnick 1999, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d Vellenga 1990, pp. 118–121.

- ^ a b Doll 2009, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vellenga 1990, pp. 127–131.

- ^ a b Worth, Fred (1992). Elvis: His Life from A to Z. Outlet. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-517-06634-8.

- ^ a b Vellenga 1990, pp. 134–140.

- ^ Randall, Mark (December 7, 2023). "Elvis and Colonel Tom Parker formed greatest partnership in showbiz history". DeSoto Times-Tribune. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Victor, The Elvis Encyclopedia, pp. 384–395.

- ^ Carr & Farren, The Complete Illustrated Record.

- ^ a b c Nash 2003, pp. 273–275.

- ^ Guralnick 1999b, p. 477.

- ^ a b c d e Guralnick 1999, p. 322.

- ^ a b c Guralnick 1999b, p. 478.

- ^ a b c d e f g Doll 2009, p. 236

- ^ a b Nash 2002, p. 229.

- ^ a b Nash 2002, pp. 286–295.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nash 2002, pp. 384–390.

- ^ Nash 2002, pp. 390–395.

- ^ a b c d e Nash 2002, pp. 298–302.

- ^ "An Elvis Biography Review … "Elvis: What Happened"". www.elvis-history-blog.com. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Victor, Adam (2008). The Elvis Encyclopedia. Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd. pp. 392–393. ISBN 978-0-7156-3816-3.

- ^ Carr, Roy (1982). Elvis: The Illustrated Record. Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-53979-9.

- ^ Nash 2002, p. 315.

- ^ a b c Jobe Pierce, Patricia (1994). The Ultimate Elvis. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 978-0-671-87022-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nash 2002, pp. 328–335.

- ^ "Photos: Elvis Presley and Colonel Tom Parker". Elvispresleymusic.com.au. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Andreas van Kuijk: Colonel Tom Parker". Elvis.com.au. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "A New Light on Colonel Tom Parker | Elvis Articles".

- ^ Van der Steen, Paul (September 14, 2020). "Staatloos na het dienen in vreemde krijgsdienst". Trouw.nl. Trouw. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Werner, Michael (August 12, 2018). "A New Light On Colonel Tom Parker". elvis.com.ua. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c Vellenga 1990, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Nash 2002, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Nash 2002, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Nash 2002, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Nash 2002, p. 329.

- ^ "In Elvis biopic, Tom Hanks plays the Tampa dogcatcher who managed the King". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Zehme, Bill (August 24, 1989). "The Rolling Stone interview: Eddie Murphy". Rolling Stone. p. 58.

- ^ Guralnick 1999b.

- ^ a b c d e Nash 2002, pp. 340–341.

- ^

Dowd, Maureen (May 22, 2022). "A Larger-Than-Life Look at a Larger-Than-Life Star". The New York Times. pp. ST10. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

Jerry Schilling, a member of the Memphis Mafia

- ^ "Meet the Fifth (Jewish) Beatle – Manager Brian Epstein". The Forward. December 4, 2013.

- ^ Rolling Stone. "'Vinyl' Recap: Long Live the King", Retrieved on March 29, 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Doll, Susan (2009). Elvis for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-47202-6.

- Guralnick, Peter (1999). Elvis Day by Day. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-42089-3.

- Guralnick, Peter (1999b). Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-33222-4.

- Nash, Alanna (2002). The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-85410-948-4.

- Vellenga, Dirk (1990). Elvis and the Colonel. Grafton. ISBN 978-0-586-20595-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Dickerson, James L. (2001). Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 9780815410881.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The All American Boy: Enter Elvis and the rock-a-billies" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Goldman, Albert (1981). Elvis. London: Allen Lane/Penguin. ISBN 0-7139-1474-2.

- Moore, Scotty; Dickerson, James L. (1997). That's Alright, Elvis:The Untold Story of Elvis's First Guitarist and Manager, Scotty Moore. Schirmer Books/Simon & Schuster.

- Nash, Alanna (2003). The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-1301-1.

- Vellenga, Dirk; Farren, Mick (1988). Elvis and the Colonel. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-440-20392-9.

External links

[edit]- Colonel Tom Parker at IMDb

- Interview with Loanne Parker

- Tom Parker collection and interviews with co workers Archived February 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ED Bonja Interview Elvis Photographer - the Elvis Information Network exclusive – Interview with En Bonja, who worked directly for the Colonel as Elvis's official photographer and tour manager

- Colonel Tom Parker's home (former), 409 Park Ridge Avenue, Temple Terrace, Fl.