Krefeld

Krefeld

Krieëvel (Limburgish) | |

|---|---|

City Hall | |

| Coordinates: 51°20′N 06°34′E / 51.333°N 6.567°E | |

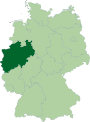

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Düsseldorf |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–25) | Frank Meyer[1] (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 137.68 km2 (53.16 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 39 m (128 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 228,550 |

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,300/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 47701-47839 |

| Dialling codes | 02151 |

| Vehicle registration | KR |

| Website | www |

Krefeld (/ˈkreɪfɛld, -ɛlt/ KRAY-feld, -felt,[3][4][5][6] German: [ˈkʁeːfɛlt] ; Limburgish: Krieëvel [ˈkʀiə˦vəl]), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War),[7] is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldorf, its center lying just a few kilometers to the west of the river Rhine; the borough of Uerdingen is situated directly on the Rhine. Because of its economic past, Krefeld is often referred to as the "Velvet and Silk City". It is accessed by the autobahns A57 (Cologne–Nijmegen) and A44 (Aachen–Düsseldorf–Dortmund–Kassel).

Krefeld's residents now speak Hochdeutsch, or standard German, but the native dialect is a Low Franconian variety, sometimes locally called Krefelder Platt, Krieewelsch Platt, or sometimes simply Platt. The Uerdingen line isogloss, separating general dialectical areas in Germany and neighboring Germanic-speaking countries, runs through and is named after Krefeld's Uerdingen district, originally an independent municipality.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Records first mention Krefeld in 1105 under the name of Krinvelde.

In February 1598, Walburga, wife of Adolf van Nieuwenaar, and last Countess of Limburg and Moers, gave the County of Moers, which included Krefeld, to Maurice, Prince of Orange. After her death in 1600, John William of Cleves took possession of these lands, but Maurice successfully defended his heritage in 1601. Krefeld and Moers would remain under the jurisdiction of the House of Orange and the Dutch Republic during the Dutch Golden Age (1588–1672).[8] Krefeld was one of few towns spared the horrors of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). The town of Uerdingen, incorporated into Krefeld in the 20th century, had been destroyed at the hands of troops from Hesse during the Thirty Years' War, and almost ceased to exist.

After the death of William III of Orange in 1702, Krefeld passed to the Kingdom of Prussia.[8] The Battle of Krefeld occurred nearby in 1758 during the Seven Years' War. Krefeld and Uerdingen were included within the Prussian Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg in 1815 (after 1822 the Rhine Province).

In 1872 Krefeld became an independent city within Rhenish Prussia. In 1918 during the First World War the Belgian Army used it as a base during the occupation of the Rhineland. In 1929 Krefeld and Uerdingen merged to form Krefeld-Uerdingen; in 1940 the name was shortened to simply Krefeld.

The Mennonites of Krefeld

[edit]From 1607 Mennonites arrived in Krefeld, as in nearby Gronau, from neighboring Roman Catholic territories where they were persecuted. In 1609 Herman op den Graeff, originally from Aldekerk, moved with his family to Krefeld. There he became a lay preacher and chairman of the Mennonite religious community. In 1637, Op den Graeff was referred to as “the Mennonite lord Bishop” (der hiesigen Mennoniten Herrn Bischof) of Krefeld in the reformed community’s minutes book.[9] They sought refuge in the lands of the more tolerant House of Orange-Nassau, at the time rulers of Krefeld; in 1657 their congregation was officially recognized and in 1693 they were allowed to build their own church, although hidden in a back yard (which still exists, reconstructed after World War II, with about 800 members). Also the Quaker Evangelists received a sympathetic audience among the larger of the German-Mennonite congregations around Krefeld, Gronau, Emden and Altona, Hamburg.[10] In 1683 a group of thirteen Mennonite families (twelve of them Mennonite-Quakers), the so called Original 13, including three of the Op den Graeff families left Krefeld to re-settle in Pennsylvania in order to enjoy religious freedom. They crossed the Atlantic on the ship Concord,[11] and founded the settlement of Germantown (now incorporated in Philadelphia), invited by William Penn, and thus beginning the Pennsylvania Dutch ethnic identity.[12] The most important Mennonite family of Krefeld were the silk merchants and silk weaving industrialists Von der Leyen who, by 1763, employed half of Krefeld's population of 6,082 in their factories. Their residence, built from 1791, is the current City Hall.

The Jews of Krefeld

[edit]Jews were listed as citizens of Krefeld from 1617. In 1764, a synagogue was erected, and by 1812, under French rule, the town included 196 Jewish families, with three Jewish-owned banks. Under Napoleon, the town became the capital for the surrounding Jewish communities including over 5000 Jews, and by 1897 they comprised 1.8% of the population.[13] In 1846 a Jewish representative was voted onto the town's municipal council, while rising antisemitism was noted during these elections.[13] A reform synagogue was built in 1876, arousing opposition from the Orthodox community. A Jewish school existed in the town, with more than 200 students around 1900.[13]

In November 1938, during the November pogroms, a synagogue on Marktstraße, as well as synagogues in Linn, Uerdingen and Hüls were destroyed, in addition to attacks on Jewish shops and homes.[14] In 1941 following an order from Hitler to deport the German Jews to the east, Jews from the town were sent to the area around Riga[15][13] and murdered there.[16]

In 2008, a new synagogue, library and Jewish cultural center were erected on the location of one of the demolished synagogues. Around 1100 Jews were reported to live in and around Krefeld at the time.[17]

World War II

[edit]On 11 December 1941, during World War II, a detailed report on the transport of Jews from Krefeld and its surroundings listed 1007 Jews from Krefeld and Duisburg, were deported to the Šķirotava Railway Station near Riga, later to become Jungfernhof concentration camp. They were transported in freezing conditions with no drinking water for more than two days.[15] Almost immediately upon arrival, they were shot in the Rumbula forest massacre.[16]

On 21 June 1943, British bombs destroyed many buildings in the east part of the city; a firestorm consumed large parts of the city center (apart from the central train station, which remained intact apart from minor damage). On 3 March 1945 US troops entered Krefeld.[18] After occupying the city and due to a lack of fluent German speakers in the intelligence unit to which he was assigned, the U.S. Army placed Henry Kissinger, then a private, in charge of the city administration.[19]

During the Cold War, the city was host to the 16th Signal Regiment of the United Kingdom's Royal Corps of Signals stationed at Bradbury Barracks.[20] The town became part of the new state of North Rhine-Westphalia after World War II.

Points of interest

[edit]

- Linn Castle (German)

- Botanischer Garten Krefeld, a municipal botanical garden

- Krefeld Zoo

- Lange and Esters Houses, neighbouring houses by early Mies van der Rohe, now serving as local contemporary art museum venues[21]

- Kaiser Wilhelm Museum,[22] contemporary art museum

- German Textile Museum

- Galopprennbahn Krefeld, horse racing track

- The well-preserved historic old towns of the formerly independent districts Uerdingen, Linn and Hüls

- Krefeld-Uerdingen Bridge, the only bridge to cross the Rhine in Krefeld

Districts

[edit]

There are a number of districts in Krefeld. Each has a municipal representative, with representatives chosen by local elections. The districts are:

|

Municipal absorptions

[edit]Cities and places that were incorporated into Krefeld:

- 1901: Linn (Stadtrecht since 1314)

- 1907: Bockum, Verberg und Oppum (all mayoralty Bockum)

- 1929:

- Krefeld became an independent city

- Uerdingen, Krefeld (received municipal law in 1255/1344, added Hohenbudberg in today's Duisburg district Friemersheim)

- Fischeln, Krefeld district

- Traar, Krefeld district

- Gellep and Stratum (in Lank), Krefeld district

- Forstwald (Vorst), Krefeld district

- Benrad und Hülserberg (Hüls), Kempen

- 1975: Locality of Hüls from Kempen (since 1970 integrated and belonged since 1929 to the Kempen-Krefeld district; in 1936 Orbroich had been independent)

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1604 | 350 | — |

| 1722 | 1,499 | +328.3% |

| 1787 | 7,896 | +426.8% |

| 1830 | 18,511 | +134.4% |

| 1871 | 57,105 | +208.5% |

| 1875 | 62,905 | +10.2% |

| 1880 | 73,872 | +17.4% |

| 1890 | 105,376 | +42.6% |

| 1895 | 107,245 | +1.8% |

| 1900 | 106,928 | −0.3% |

| 1905 | 110,344 | +3.2% |

| 1910 | 129,406 | +17.3% |

| 1919 | 124,325 | −3.9% |

| 1925 | 131,098 | +5.4% |

| 1933 | 165,305 | +26.1% |

| 1939 | 170,968 | +3.4% |

| 1950 | 171,875 | +0.5% |

| 1961 | 213,104 | +24.0% |

| 1970 | 222,700 | +4.5% |

| 1975 | 230,500 | +3.5% |

| 1980 | 223,400 | −3.1% |

| 1985 | 217,000 | −2.9% |

| 1990 | 244,020 | +12.5% |

| 2001 | 239,559 | −1.8% |

| 2011 | 222,247 | −7.2% |

| 2022 | 230,666 | +3.8% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions.

Source for 1990-2022: [24] | ||

|

|

¹ Census data

Largest migrant communities in Krefeld by 31.12.2017 are

| 7,805 | |

| 4,510 | |

| 2,610 | |

| 2,530 | |

| 2,225 | |

| 1,942 | |

| 1,386 | |

| 1,036 | |

| 872 | |

| 740 |

Politics

[edit]Mayor

[edit]The current mayor of Krefeld is Frank Meyer of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), elected in 2015 and re-elected in 2020. The most recent mayoral election was held on 13 September 2020, with a runoff held on 27 September, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Frank Meyer | Social Democratic Party | 36,025 | 43.4 | 37,125 | 62.4 | |

| Kerstin Jensen | Christian Democratic Union | 22,901 | 27.6 | 22,366 | 37.6 | |

| Thorsten Hansen | Alliance 90/The Greens | 12,778 | 15.4 | |||

| Martin Vincentz | Alternative for Germany | 4,186 | 5.0 | |||

| Joachim C. Heitmann | Free Democratic Party | 3,578 | 4.3 | |||

| Richard Jansen | Die PARTEI | 1,551 | 1.9 | |||

| Salih Tahusoglu | We Make Krefeld | 1,047 | 1.3 | |||

| Andreas Drabben | Independent Voters' Association/Free Voters | 783 | 0.9 | |||

| Peter Lommes | German Communist Party | 207 | 0.2 | |||

| Valid votes | 83,056 | 98.8 | 59,491 | 99.0 | ||

| Invalid votes | 990 | 1.2 | 612 | 1.0 | ||

| Total | 84,046 | 100.0 | 60,103 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 180,496 | 46.6 | 180,256 | 33.3 | ||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

The following is a list of mayors of Krefeld from 1848:[citation needed]

- 1848–1872: Ludwig Heinrich Ondereyck

- 1872–1881: Friedrich Christian Roos

- 1882–1903: Ernst Küper

- 1903–1905: Wilhelm Hammerschmidt

- 1905–1911: Adalbert Oehler

- 1911–1930: Johannes Johansen

- 1945–1946: Johannes Stepkes

- 1946–1947: Wilhelm Warsch

- 1947–1949: Hermann Passen

- 1949–1951: Hanns Müller (FDP)

- 1951–1956: Johannes Hauser (CDU)

- 1956–1961: Josef Hellenbrock (SPD)

- 1961–1968: Herbert van Hüllen (CDU)

- 1968–1982: Hansheinz Hauser (CDU)

- 1982–1989: Dieter Pützhofen, first term in office (CDU)

- 1989–1994: Willi Wahl (SPD)

- 1994–2004: Dieter Pützhofen, second term in office (CDU)

- 2004–2015: Gregor Kathstede (CDU)

- 2015–present: Frank Meyer (SPD)

The following is a list of city counsellors from 1946 until 1999:

- 1946–1949: Johan Stepkes

- 1949–1964: Bernhard Heun

- 1964–1986: Hermann Steffens

- 1986–1988: Alfred Dahlmann

- 1988–1999: Heinz-Josef Vogt

City council

[edit]

The Krefeld city council governs the city alongside the mayor. The most recent city council election was held on 13 September 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 24,977 | 30.2 | 17 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 23,599 | 28.6 | 17 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 16,662 | 20.2 | 12 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 4,834 | 5.9 | 3 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 4,476 | 5.4 | 3 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 2,664 | 3.2 | 2 | |||

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | 2,031 | 2.5 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| We Make Krefeld (WIR) | 1,200 | 1.5 | New | 1 | New | |

| Independent Voters' Association/Free Voters (UWG/FW) | 1,023 | 1.2 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Voters' Association Our Future (WUZ) | 842 | 1.0 | New | 1 | New | |

| Independents | 267 | 0.3 | – | 0 | – | |

| German Communist Party (DKP) | 7 | 0.0 | New | 0 | New | |

| Valid votes | 82,582 | 98.5 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 1,216 | 1.5 | ||||

| Total | 83,798 | 100.0 | 58 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 180,491 | 46.4 | ||||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

Transport

[edit]

Krefeld is connected to the Deutsche Bahn network with several stations, including its main station, Krefeld Hauptbahnhof. They are served by Intercity, Regional-Express and Regionalbahn trains. The Düsseldorf-based Rheinbahn operates a Stadtbahn service to the centrally located Rheinstraße stop. This line was the first electric inter-city rail line in Europe, established in 1898, and commonly called the K-Bahn because of the letter "K" used to denote the trains to Krefeld. Nowadays, in the VRR notation, it is called U76, with the morning and afternoon express trains numbered as U70, the line number there coloured red instead of the usual blue used for U-Bahn lines. The term K-Bahn, however, prevails in common usage.

The city of Krefeld itself operates four tramway and several bus lines under the umbrella of SWK MOBIL, a city-owned company. Since 2010, 19 of the oldest trams of the type Duewag GT8 were replaced by modern barrier-free trams of the type Bombardier Flexity Outlook. SWK Mobil owns an option to buy another 19 trams of the same type to replace the last 19 Duewag M8 trams. The whole tram fleet will then be barrier-free. Next to that the city plans to extend the line 044 in Krefeld-Hüls to connect the northern district of Hüls with the Krefeld downtown area.

Economy

[edit]The headquarters of Fressnapf, a pet food retailer franchise company, are situated in Krefeld.

The Nirosta steelworks, once owned by ThyssenKrupp, was sold in 2012 to Outokumpu.[25]

International relations

[edit]Since 1964,[26] the city has hosted an "honors program in foreign language (German) studies" for high school students from Indiana, United States. The program annually places approximately thirty carefully selected high school juniors with families in and around Krefeld for intensive German language training.[27] Since 1973, the fire services of Krefeld and twin city Leicester have played each other in an annual 'friendly' football match.[28]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Venlo, Netherlands (1964)

Venlo, Netherlands (1964) Leicester, England, United Kingdom (1969)

Leicester, England, United Kingdom (1969) Dunkirk, France (1974)

Dunkirk, France (1974) Leiden, Netherlands (1974)

Leiden, Netherlands (1974) Charlotte, United States (1986)

Charlotte, United States (1986) Oder-Spree (district), Germany (1990)

Oder-Spree (district), Germany (1990) Ulyanovsk, Russia (1993) - put on hold since 2022 due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Ulyanovsk, Russia (1993) - put on hold since 2022 due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine Kayseri, Turkey (2009)

Kayseri, Turkey (2009) Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine (2023)

Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine (2023)

Notable people

[edit]Scientists and academics

[edit]- Charlotte Auerbach (1899–1994) – genetic scientist

- Edmund ter Meer (1859–1931) – chemist and industrialist

- Felix Kracht (1912–2002) – aerospace engineer, an Airbus pioneer and former Senior Vice President

- Fritz ter Meer (1884–1967) – chemist and industrialist

- Leopold Löwenheim (1878–1957) – logician

- Herta Wescher (1899–1971), art historian and art critic[30]

- Max Zorn (1906–1993) – mathematician

- Rudi Dornbusch (1942–2002) – economist

- Kate Wallach (1905-1979)

Writers, poets and journalists

[edit]- Bernhard Hennen (born 1966) – writer of fantasy literature

- Bodo Hauser (1946–2004) – journalist and writer

- Erol Yesilkaya (born 1976) – Turkish-German screenwriter

- Johannes Floehr (born 1991) – author and comedian

- Kurt Feltz (1910–1982) – poet

- Margarethe Schreinemakers (born 1958) – television presenter and journalist

Musicians

[edit]- Albert Dohmen (born 1956) – opera singer

- Andrea Berg (born 1966) – singer

- Blind Guardian (1984-) – Power Metal band

- Engin Nurşani (1984–2020) – folk musician

- Heinrich Band (1821–1860) – inventor of the bandoneón

- Maria Madlen Madsen (1905–1990) – opera singer

- Ralf Hütter (born 1946) – leader of electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk

- Saki Kaskas (1971–2016) – Greek-Canadian video game music composer

Visual artists

[edit]- Albert Oehlen (born 1954) – artist

- Charles J. Kleingrothe (1864–1925) – photographer

- Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957) – German-Dutch painter and graphic designer

- Johan Thorn Prikker (1868–1932) – Dutch artist

- Johannes Itten (1888–1967) – Swiss expressionist painter, designer, teacher, writer and theorist

- Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) – artist

- Markus Oehlen (born 1956) – artist

- Theo Akkermann (1907–1982) – sculptor

Sportspeople

[edit]- Jochen Neerpasch (born 1939) – racing driver

- Friedhelm Funkel (born 1953) – football manager and player

- Juliane Schenk (born 1982) – German badminton player

- Martin Hyun (born 1979) – German-American ice hockey player and author

- Philip Hindes (born 1992) – British sprint cyclist

- Werner Rittberger (1891–1975) – figure skater

- Marc Schaub (born 1992) – professional ice hockey player

- Nicole Anyomi (born 2000) – football player

Businessmen

[edit]- Ben Neumann (1966–2020) – American entrepreneur and film producer

- Edmund ter Meer (1859–1931) – chemist and industrialist

- Felix Kracht (1912–2002) – aerospace engineer, an Airbus pioneer and former Senior Vice President

- Fritz ter Meer (1884–1967) – chemist and industrialist

- Thierry Hermès (1801–1878) – French businessman and founder of Hermès

Military personnel

[edit]- Emil Schäfer (1891–1917) – World War I aviator

- Heinz Harmel (1906–2000) – SS commander, Knight's Cross Holder

- Werner Voss (1897–1917) – World War I aviator

Politicians

[edit]- Jürgen Lenders (born 1966), politician (FDP)

Mennonites

[edit]- Herman op den Graeff (1585-1642), born in Aldekerk; Mennonite community leader from Krefeld, in 1632 delegate to sign the Dordrecht Confession of Faith

- Abraham op den Graeff (1646-1731), grandchild of the previous one, born in Krefeld; original founder of Germantown, Pennsylvania, member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly and in 1688 signer of the first organized religious protest against slavery in colonial America

References

[edit]- ^ Wahlergebnisse in NRW Kommunalwahlen 2020 Archived 17 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Land Nordrhein-Westfalen, accessed 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Nordrhein-Westfalens am 31. Dezember 2023 – Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes auf Basis des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Krefeld". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Krefeld". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Krefeld". Lexico US English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Krefeld". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Staff. "The Western Front". The Observer. Vol. 248 No. 7, 737. London. p. 9, col. 3. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ a b Ada Peele, Een uitzonderlijke erfgenaam: De verdeling van de nalatenschap van Koning-Stadhouder Willem III, Uitgeverij Verloren, 2013, Germany, pp. 36-39.

- ^ Taufgesinnte und großes Kapital: die niederrheinisch-bergischen Mennoniten und der Aufstieg des Krefelder Seidengewerbes, Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts-1815. Page 105. Von Peter Kriedte (2007)

- ^ C. Henry Smith, Smith's Story of the Mennonites, p. 139 (1981, 5th ed. Faith and Life Press) ISBN 0-87303-060-5

- ^ Germantown Historical Society: Founders of Germantown; Jones, Iris Carter: Krefeld Immigrants

- ^ C. Henry Smith, Smith's Story of the Mennonites, p. 360

- ^ a b c d Jews of Krefeld Archived 23 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Yad Vashem website. Town citizen Isaac Meyer Fuld, a member of the family of Heinrich Heine, was a prominent bank-owner in Germany at the time.

- ^ "Teil 52: 9./10. November 1938 Die Synagoge wird zerstört | Stadt Krefeld" [Part 52: 9/10 November 1938 The synagogue is destroyed]. Krefeld.de (in German). 22 November 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b Report on Jewish Deportation to Riga Archived 23 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (Hebrew Translation of German document by Yad Vashem),

- ^ a b (German) Gottwald, Fred, and Schulle, Diana: Die „Judendeportationen“ aus dem Deutschen Reich 1941–1945. (The Jewish deportations by the German Empire from 1941 to 1945.) Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5, p.121 I heard that the Jews were evacuated in rows - and as they left the train - they were shot" (Victor Klemperer, diary entry of 13 January 1942)

- ^ New synagogue opens in Krefeld Archived 23 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (English, Deutsche Welle website)

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (1992). Kissinger : a biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-66323-2. OCLC 25787497.

- ^ Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography, p.48.

- ^ "Bradbury Barracks". Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Kunstmuseen Krefeld". www.kunstmuseenkrefeld.de. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Kunstmuseen Krefeld". www.kunstmuseenkrefeld.de. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Herzlich willkommen im Museumszentrum Burg Linn! Besuchen Sie unser Museum". www.archaeologie-krefeld.de. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Germany: States and Major Cities".

- ^ Gerlach, Marilyn; Vassinen, Eero (31 January 2012). "Outokumpu to buy Thyssen stainless steel unit in $3.5". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "History of IUHPFL: About Our Office: Indiana University Honors Program in Foreign Languages for High School Students: Indiana University". iu.edu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Indiana University Honors Program in Foreign Languages for High School Students: Indiana University". indiana.edu. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ Brown, Tom (31 July 2013). "Twin towns: Do we still need them?". BBC East Midlands Today. BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaften". krefeld.de (in German). Krefeld. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Wescher, Hertha". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 14 March 2024.