German Sign Language

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) |

| German Sign Language | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native to | Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg |

Native speakers | Between 80,000 and 395,000 (2014)[1] |

German Sign Language family

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | gsg |

| Glottolog | germ1281 |

Areas where German Sign Language is a national language Areas where German Sign Language is in significant use alongside another sign language | |

German Sign Language (German: Deutsche Gebärdensprache, DGS) is the sign language of the deaf community in Germany, Luxembourg[2] and in the German-speaking community of Belgium[citation needed]. It is unclear how many use German Sign Language as their main language; Gallaudet University estimated 50,000 as of 1986. The language has evolved through use in deaf communities over hundreds of years.

Recognition

[edit]Germany has a very strong oralist tradition and historically has seen a suppression of sign language. German Sign Language was first legally recognised in The Federal Disability Equality Act (2002) in May 2002.[3] Since then, deaf people have a legal entitlement to Sign Language interpreters when communicating with federal authorities, free of charge.[4]

Very few television programs include an interpreter; those that do are the news and a news "round-up". There is at least one programme conducted entirely in German Sign Language called Sehen statt Hören (Seeing Instead of Hearing), a documentary-style programme produced by the Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) and broadcast on Saturday mornings on Bayerischer Rundfunk and the other regional state broadcasters in Germany.

In 2018, the Luxembourgish Chamber of Deputies voted unanimously to recognise German Sign Language.[2]

German and German Sign Language

[edit]German Sign Language is unrelated to spoken German. While spoken German builds sentences following a subject – verb – object pattern, German Sign Language uses a subject object verb strategy.[5] Thus, the two have very different grammars, though as the dominant language of the region, German has had some influence on German Sign Language. A signed system that follows German grammar, Signed German (Lautsprachbegleitende Gebärden or Lautbegleitende Gebärden, "sound-accompanying signs"), is used in education. It is not used as a natural means of communication between deaf people. Another system of manually representing German is cued speech, known as Phonembestimmes Manualsystem (Phonemic Manual System).

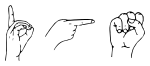

Manual alphabet and fingerspelling

[edit]

German Sign Language uses a one-handed manual alphabet ('Fingeralphabet' in German) derived from the French manual alphabet of the 18th century; it is related to manual alphabets used across Europe and in North America. It differs from the ASL manual alphabet in the shape of the letter T and in the addition of a letter SCH (a 'five' hand). The additional letters for Ä, Ö, Ü, and ß are formed by moving the letters for A, O, U, and S a short distance downwards.

Dialects and related languages

[edit]Regional variants of German Sign Language include Hamburg, Berlin, and Munich sign. Sign languages of regions in the former East Germany have a greater divergence from sign languages of the western regions; some may be unrelated. Polish Sign Language is descended from German Sign Language. Israeli Sign Language may be as well, as it evolved from the sign language used by German Jewish teachers who opened a school for deaf children in Jerusalem in 1932, and still shows some resemblance to its German counterpart. It is not related to Austrian Sign Language, which is used in parts of southern Germany, nor to Swiss Sign Language, both of which are part of the French Sign Language family, though they have had some influence from German Sign Language.

Notation systems

[edit]Everyday users of German Sign Language use no written form of the language. In academic contexts, German Sign Language is usually described with the Hamburg notation system or HamNoSys. SignWriting also has its adherents in Germany.

Grammar

[edit]The grammar of German Sign Language may be described in terms of the conventional linguistic categories phonology, morphology, morphosyntax and syntax.

Phonology

[edit]Signs are made up of a combination of different elements from each of the classes of distinctive features: handshape, hand orientation, location and movement. If one of these elements is changed, it can result in a sign with a completely different meaning. Two signs differing in only one element are deemed to be a minimal pair. German Sign Language uses 32 handshapes, of which six are basic handshapes found in all sign languages.

Two-handed signs are signs which are necessarily performed with both hands. Their formation is in accordance with certain phonotactic limitations, such as the rule of symmetry (when both hands move at the same time, they have the same handshape) and the rule of dominance (if the two hands have different handshapes, only the dominant hand is moved while the non-dominant hand remains passive).

Uninflected lexical signs in German Sign Language have at most two syllables. Syllables consist of two syllabic positions, described as Hold (H) and Movement (M). Holds consist of the handshape together with the hand orientation (together referred to as the hand configuration) at a specific location in signing space. Holds do not contain any change of location (movement from one location to another). Movements, on the other hand, involve a change of location and may involve secondary movements such as wiggling of the fingers. Syllables may then be grouped into the following types: M (the minimal syllable), HM, MH, HMH (the maximal syllable). In the case of HM syllables, for example, the hand configuration of the Movement moves away from the location of the Hold. A syllable of type M can consist of the following specifications: a path movement (from one location to another), a path movement with secondary movement (such as wiggling or twisting), or a secondary movement without path movement. The syllable type H (a segment without a Movement) is not allowed for phonotactical reasons.

An elementary component of lexical signs are non-manual lexical markings, such as movements of eyes (rolling, widening), mouth (puffing, rounding) and face, as well as the whole head (nodding, tilting) and upper body (leaning). These are obligatory accompaniments of a quarter of all lexical signs. Making visual syllables with the mouth is referred to as mouthing.

Syntax

[edit]Clause structure

[edit]Unmarked word order

[edit]The unmarked word order in DGS is subject-object-verb, similar to languages such as Turkish, Japanese and Latin, but differing from German.

[PRON]2

you

subject

ARBEIT

work

object

SUCH-

search

verb

'You are looking for a job.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

BROT

bread

Object

1GEB-2[cl:Brot]

I-give-you(-something-bread-shaped)

Verb

'I give you (the) bread.'

If an indirect object appears in the sentence, it stands before the direct object.

[PRON]1

I

Subject

[POSS]1 VATER3

my father

indirect object

BROT

bread

direct object

1GEB-3[cl:Brot]

I-give-him(-something-bread-shaped)

verb

'I give my father (the) bread.'

In sentences with chains of verbs, auxiliary verbs and similar usually appear after the full verb, the opposite of English word order.

[PRON]2

you

Subject

ARBEIT

work

object

SUCH-

search

"full verb"

MÜSS-

must

"auxiliary"

'You have to look for a job.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

RADFAHR-

ride-a-bike

"full verb"

KÖNN-NICHT

cannot

"auxiliary

'I can't ride a bike.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

KOMM-

come

"full verb"

VERSUCH-

try

"auxiliary"

'I'll try to come.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

WOHNUNG

apartment

Object

PUTZ-

clean

"full verb"

KEINE-LUST-HAB-

can't-be-bothered

"Modalverb"

'I can't be bothered cleaning the apartment.'

The Personal Agreement Marker (glossed as "PAM"), which looks almost like the sign for "person" and may be accompanied by the mouthing "auf" ("on"), is a sign used to indicate the location in signing space of animate objects when the verb in the sentence does not do this. It roughly fills the roll of object pronouns, however it seems to function more as an auxiliary verb, inflecting for person where the main verb does not. Although there is considerable variation, especially across dialects, it tends to occur where auxiliaries occur, after the verb, rather than in the object slot. The benefactive marker (glossed as "BEM") is similarly placed.

[PRON]1

I

Subject

LIEB-

love

"full verb"

[PAM]2

you

"auxiliary"

'I love you.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

ARZT3

doctor

Object

LIEB-

love

"full verb"

[PAM]3

him/her

"auxiliary"

'I love the doctor.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

BUCH

book

object

KAUF-

buy

"full verb"

[BEM]2

for-you

"auxiliary"

'I bought a book for you.'

Time expressions (tomorrow, next week) appear at the beginning of the sentence (as a discourse topic).

GESTERN

yesterday

Time

FRAU3

woman

Subject

[POSS]1 SCHWESTER4

my sister

Indirect object

BUCH

book

Direct object

3GEB-4[cl:Buch]

she-give-her(-something-book-shaped)

Verb

'Yesterday a/the woman gave my sister a/the book.'

Phrases specifying location tend to occur at the beginning of the sentence (after the time information).

GESTERN

yesterday

Time

UNIVERSITÄT [LOK]A

university there

Location

[PRON]1

I

Subject

MANN NETT

man nice

Object

KENNENLERN-

meet

Verb

'I met a nice man at the university yesterday.'

This follows the figure-ground-principle, according to which smaller, more mobile referents (figures) tend to occur after larger, less mobile referents (ground).

WALDA

forest

Ground

HAUS

house

Figure

STEH-in-A[cl:Haus]

house-shaped-object-is-situated-there

Verb

'There is a house in the forest.'

Sentence adverbs often appear at the beginning of the sentence.

HOFF

hope

Sentence adverb

[PRON]3

s/he

Subject

HUND

dog

Object

KAUF-

buy

Verb

'Hopefully s/he'll buy a dog.'

However, adverbs that modify the verb but which cannot be expressed non-manually follow the verb as an extra clause.

[POSS]1 CHEF

my boss

Subject

TANZ-,

dance

Verb

SCHÖN

beautiful

Adverbial clause

'My boss dances beautifully. / My boss dances and it's beautiful.'

Wh-words (interrogatives) usually occur at the end of the sentence after the verb.

[PRON]2

you

Subject

BESTELL-

order

"full verb"

WÜNSCH-

desire

"auxiliary"

WAS

what

Wh

'What would you like to order?'

[PRON]2

you

Subject

D-G-S

DGS

object

LERN-

learn

"full verb"

WÜNSCH-

desire

"auxiliary"

WARUM

why

Wh

'Why do you want to learn DGS?'

[PRON]2

du

Subject

SOZIAL WISSENSCHAFT

social sciences

Object

STUDIER-

study-at-university

"full verb"

ANFANG-

begin

"auxiliary"

WANN

when

Wh

'How long have you been studying social sciences at university?'

Some signs with a negative meaning tend to occur at the end of the sentence.

[PRON]1

ich

Subject

[POSS]2 GELIEBTE(R)

your partner

Object

KENNENLERN-

meet

Verb

NOCH-NICHT

not-yet

Negation

'I haven't met your girlfriend/boyfriend/partner/husband/wife yet.'

[PRON]1

I

Subject

ESS-

eat

"full verb"

WÜNSCH-

desire

"auxiliary"

NICHTS

nothing

negation

'I don't want to eat anything (at all).'

However, if the negation is not emphasised, it can also appear in the expected position.

[PRON]1

I

Subject

NICHTS

nothing

object

ESS-

eat

"full verb"

WÜNSCH-

desire

"auxiliary"

'I don't want to eat anything.'

Determiners (articles, demonstratives, quantifiers, relative pronouns) follow the noun.

BUCH

book

Noun

[DEM]A

this

Determiner

'this book'

Their function is to set the location of referents within the signing space. If this is indicated instead by directional verbs, determiners can always be omitted, provided they are not required for other reasons (such as showing possession, pluralisation, etc.) There is no distinction between definite and indefinite articles.

Attributive adjectives follow immediately after the noun.

BUCH

book

Noun

NEU

new

Adjective

'a/the new book'

The copula to be does not exist in DGS. Predicative adjectives are generally separated from the noun by a determiner.

BUCH

book

Noun

[DEM]A

this

Determiner

NEU

new

Adjective

'This book is new.'

Compare the preceding sentence to the following noun phrase, in which the determiner follows the adjective.

BUCH

book

Noun

NEU

new

Adjective

[DEM]A

this

Determiner

'this new book'

Possessive adjectives stand between the possessor and the possession.

MANN3

man

Possessor

[POSS]3

his

Possessive

AUTO

car

Possession

'the man's car'

Here is an example of a longer but nevertheless simple, unmarked sentence.

LETZTE-WOCHE

last-week

Time

[POSS]1 VATER3 [POSS]3 HAUS [LOK]A

my father his house there

Location

[PRON]2

you

Subject

[POSS]1 MUTTER4

my mother

Indirect object

GELD

money

Direct object

2GEB-4

you-give-her

"full verb"

WÜNSCH-

desire

"auxiliary"

WARUM

why

Wh

'Why did you want to give my mother money at my father's house last week?'

Marked sentences

[edit]Parts of the sentence which are moved outside of their usual unmarked position are accompanied by non-manual marking.

Sentence elements (with the exception of verbs) can be topicalised by being moved to the beginning of the sentence and marked with raised eyebrows.

eyebrows raised

FRAU [DEM]A

woman that

Topicalised object

[PRON]1

I

Subject

head shake

MÖG-

don't-like

Verb

'I don't like that woman. / That woman, I don't like.'

Often, a topic doesn't otherwise have any other role in the sentence. In these cases, it represents a limitation of the scope of the sentence. Compare the following three sentences.

[PRON]1

I

Subject

ITALIEN

Italy

Object

LIEBHAB-

adore

Verb

'I love Italy.'

eyebrows raised

LAND

country

Topic

[PRON]1

I

Subject

ITALIEN

Italy

Object

LIEBHAB-

adore

Verb

'My favourite country is Italy.'

eyebrows raised

ESSEN

food

Topic

[PRON]1

I

Subject

ITALIEN

Italy

Object

LIEBHAB-

adore

Verb

'My favourite food is Italian.'

References

[edit]- ^ German Sign Language at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ a b "German sign language unanimously recognised". RTL Today.

- ^ "ANED – countries – Germany – Facts and figures". disability-europe.net. Retrieved March 20, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Deutscher Gehörlosen-Bund e.V.

- ^ Bross, Fabian; Hole, Daniel (2017). "Scope-taking strategies and the order of clausal categories in German Sign Language". Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics. 2. doi:10.5334/gjgl.106.

Further reading

[edit]- "German Sign Language Dictionary" – Maisch, Günther, and Fritz-H. Wisch (1987–89). Gebärden-Lexikon. Hamburg: Verlag hörgeschädigter Kinder.

- "German Sign Language" Rammel, Georg (1974). Die Gebärdensprache: Versuch einer Wesenanalyse. Berlin-Charlottenburg: Marhold.

- "Signed German" Hogger, Birgit (1991). Linguistische Überlegungen zur lautsprachbegleitenden Gebärdung. Hörgeschädigtenpädagogik, v.45 no.4, p. 234-237

- Daniela Happ, Marc-Oliver Vorköper: Deutsche Gebärdensprache : Ein Lehr- und Arbeitsbuch. Fachhochschulverlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-936065-76-4

- Helen Leuninger: Gebärdensprachen : Struktur, Erwerb, Verwendung. Buske, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-87548-353-7

- Bross F (2020). The clausal syntax of German Sign Language (pdf). Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3560718. ISBN 978-3-96110-219-8.

External links

[edit]- Deaf and Sign Language Research Team Aachen – DESIRE (Aachen) Archived 2014-02-08 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Full list of online DGS dictionaries (Internet Archive copy, 26 Aug 2008)

- Institute of German Sign Language and Communication of the Deaf (in German)

- Rheinisch-Westfälischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen (RWTH Aachen University of Technology) (in German)

- Website of the German National Association of the Deaf (in German)