Saint Elias Mountains

| Saint Elias Mountains | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Logan |

| Elevation | 5,959 m (19,551 ft)[1] |

| Listing | List of mountain ranges |

| Coordinates | 60°34′02″N 140°24′19″W / 60.56722°N 140.40528°W[2] |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 300 mi (480 km) |

| Width | 90 mi (140 km) |

| Area | 112,509 km2 (43,440 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| Countries | United States and Canada |

| Provinces | Yukon and British Columbia |

| State | Alaska |

| Range coordinates | 60°30′N 139°30′W / 60.500°N 139.500°W |

| Parent range | Pacific Coast Ranges |

| Borders on | Wrangell Mountains |

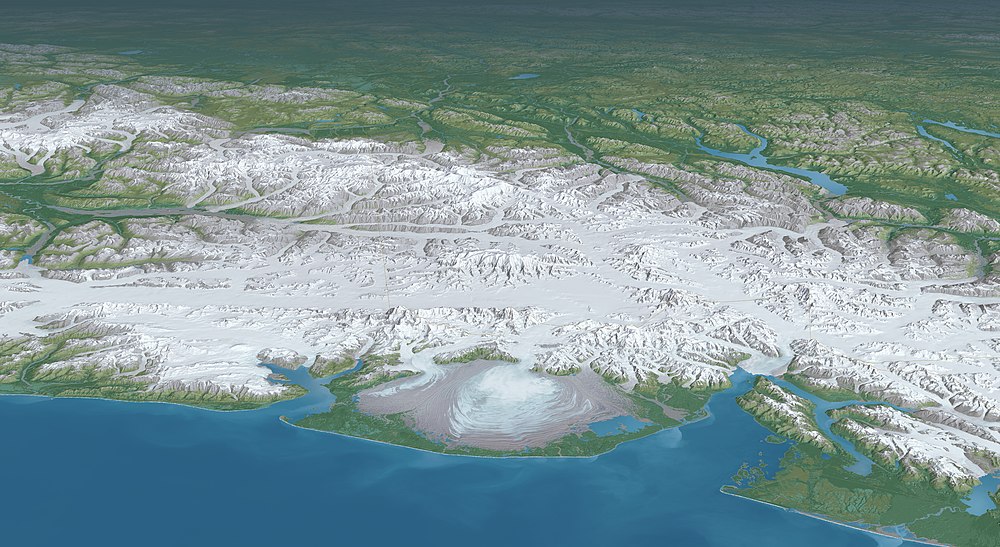

The Saint Elias Mountains (French: Chaîne Saint-Élie) are a subgroup of the Pacific Coast Ranges, located in southeastern Alaska in the United States, Southwestern Yukon and the very far northwestern part of British Columbia in Canada. The range spans Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve in the United States and Kluane National Park and Reserve in Canada and includes all of Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska. In Alaska, the range includes parts of the city/borough of Yakutat and the Hoonah-Angoon and Valdez-Cordova census areas.[3]

This mountain range is named after Mount Saint Elias, which in turn was named in 1741 by the Danish-born Russian explorer Vitus Bering.[4]

Geology

[edit]The Saint Elias Mountains form the highest coastal mountain range on Earth. It formed due to the subduction of the Yakutat microplate underneath the North American Plate. The Yakutat microplate is a wedge shaped oceanic plateau with a thickness of 20 to 30 kilometres (12 to 19 mi).[5] Similar to the adjacent Pacific Plate, which has a crustal thickness of 7 kilometres (4.3 mi), the Yakutat plate is moving northwestward at a rate of 50 millimetres (2 in) per year with respect to North America.[6] The Yakutat plate is transported northwards along the active Fairweather Fault, which probably started more than 35 million years ago.[7] Due to its thickness, the Yakutat plate is buoyant, resulting in surface uplift of the overriding North American plate, which formed the Talkeetna Mountains and the Alaska Range in Southcentral Alaska, located above the subducted part of the Yakutat plate.[7]

The Saint Elias Mountains formed at the plate boundary between the Yakutat and North American plates. The up-to-12-kilometre (7.5 mi)-thick sediments that have been deposited on top of the Yakutat plate became imbricated and deformed as they were scraped off and compose today the southern (coastal) flanks of the St. Elias Mountains. In contrast the high elevated regions of the drainage divide (Bagley Icefield, Seward Glacier) and north of it are composed of rocks that are part of the North American plate.[8] The highest peaks of the St. Elias Mountains are located in the high ice field region of the Kluane National Park (Mount Logan, Mount Vancouver) and north of the Malaspina Glacier (Mount Saint Elias, Mount Cook), in the region known as the St. Elias syntaxis. At the syntaxis region the tectonic style changes from strike-slip motion along the Fairweather Fault to collision west of Malaspina Strait. This tectonic transition concentrates stress in the crust at the syntaxis that together with efficient glacial erosion results in positive feedback processes that through time forms extreme high mountain peaks and local relief, and rapid exhumation of rocks from up to 10 km (6.2 mi) depths to the surface.[9]

Ranges

[edit]The mountains are divided by the Duke Depression, with the shorter, more rounded Kluane Ranges to the east, and the higher Icefield Ranges to the west. Sub-ranges of the Saint Elias include the Alsek Ranges, the Fairweather Range, and the Centennial Range.[10]

Highest mountains

[edit]The highest mountains of the range include:

Image

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Topographic map of Mount Logan". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- ^ "Mount Logan". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- ^ "Saint Elias Mountains". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ "Saint. Elias Mountains". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- ^ Christeson, G.L.; Gulick, S.P.; van Avendonk, H.J.; Worthington, L.L.; Reece, R.S.; Pavlis, T.L. (2010). "The Yakutat terrane: Dramatic change in crustal thickness across the Transition fault, Alaska". Geology. 38 (10): 895–898. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..895C. doi:10.1130/G31170.1.

- ^ Elliott, J.L.; Larsen, C.F.; Freymueller, J.T.; Motyka, R.J. (2010). "Tectonic block motion and glacial isostatic adjustment in southeast Alaska and adjacent Canada constrained by GPS measurements". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (B9): B09407. Bibcode:2010JGRB..115.9407E. doi:10.1029/2009JB007139.

- ^ a b Finzel, E.S.; Trop, J.M.; Ridgway, K.D.; Enkelmann, E. (2011). "Upper plate proxies for flat-slab subduction processes in southern Alaska". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 303 (3–4): 348–360. Bibcode:2011E&PSL.303..348F. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.01.014.

- ^ Plafker, G.; Berg, H.C., eds. (1994). The Geology of Alaska. Boulder: Geological Society of America. pp. 389–449. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ Enkelmann, E.; Zeitler, P.K.; Pavlis, T.L.; Garver, J.I.; Ridgway, K.D. (2009). "Intense localized rock uplift and erosion in the St. Elias orogen of Alaska". Nature Geoscience. 2 (5): 360–363. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..360E. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.210.7143. doi:10.1038/NGEO502.

- ^ "Saint Elias Mountains". Bivouac.com. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ Mount Fairweather is only partly in British Columbia. The highest peak entirely within British Columbia is Mount Waddington in the Coast Range, 4019 m (13186 ft).

- Sources

- Richter, Donald H.; Preller, Cindi C.; Labay, Keith A.; Shew, Nora B. (2006). Geologic Map of the Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska. USGS Scientific Investigations Map 2877.

- Winkler, Gary R. (2000). A Geologic Guide to Wrangell—Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska: A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes. USGS Professional Paper 1616. ISBN 978-0-607-92676-7.

- Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen, eds. (1990). Volcanoes of North America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43811-7.