Chengdu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Chengdu

成都市 Chengtu | |

|---|---|

| City of Chengdu | |

| Nicknames: | |

| |

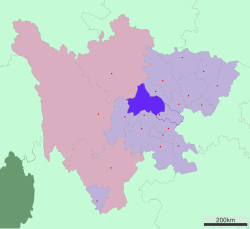

Location of Chengdu City jurisdiction in Sichuan | |

| Coordinates (Tianfu Square): 30°39′36″N 104°03′48″E / 30.66000°N 104.06333°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Sichuan |

| Municipal seat | Wuhou District |

| Divisions - County-level | 12 districts, 5 county-level cities, 3 counties |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • Body | Chengdu Municipal People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Cao Lijun |

| • Congress Chairman | Li Zhongbin |

| • Mayor | Wang Fengchao |

| • CPPCC Chairman | Zhang Shan |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level and sub-provincial city | 14,378.18 km2 (5,551.45 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,679.9 km2 (1,420.8 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,558.8 km2 (1,760.2 sq mi) |

| • Downtown | 465.88 km2 (179.88 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 500 m (1,600 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 5,364 m (17,598 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 378 m (1,240 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[3] | |

| • Prefecture-level and sub-provincial city | 20,937,757 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 15,419,445 |

| • Urban density | 4,200/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 16,045,577 |

| • Metro density | 3,500/km2 (9,100/sq mi) |

| • Major Ethnic group | Han |

| GDP[4] | |

| • Prefecture-level & sub-provincial city | CN¥ 2.207 trillion US$ 325 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 103,500 US$ 15,250 |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 610000–611944 |

| Area code | (0)28 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-SC-01 |

| License Plate Prefix | 川A and 川G |

| Tree | Ginkgo biloba |

| Flower | Hibiscus mutabilis |

| HDI (2015) | 0.791[5] (21st) – high |

| Website | Chengdu.gov.cn |

| Chengdu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Chengdu" in Chinese characters. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 成都 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Chéngdū | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chengtu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The Established Capital City" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former name | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xījīng | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 西京 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Western Capital | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Nicknames | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of Brocade | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 錦城 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 锦城 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Brocade City | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| City of Hibiscus | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 蓉城 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Hibiscus City | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Chengdu[a] is the capital city of the Chinese province of Sichuan. With a population of 20,937,757 at the 2020 census,[6] it is the fourth most populous city in China, and it is the only city with a population of over 20 million apart from direct-administered municipalities. It is traditionally the hub of Western China.

Chengdu is in central Sichuan. The surrounding Chengdu Plain is known as the "Country of Heaven"[b] and the "Land of Abundance." Its prehistoric settlers included the Sanxingdui culture. The site of Dujiangyan, an ancient irrigation system, is designated as a World Heritage Site.[7] The Jin River flows through the city. Chengdu's culture largely reflects that of its province, Sichuan; in 2011, it was recognized by UNESCO as a city of gastronomy.[8] It is associated with the giant panda, a Chinese national symbol, which inhabits the area of Sichuan; the city is home to the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding.

Founded by the Kingdom of Shu in 4th century BC, Chengdu is unique as the only major Chinese settlement that has maintained its name unchanged throughout the imperial, republican, and communist eras for more than two thousand years. It was the capital of Liu Bei's Shu Han Empire during the Three Kingdoms Era, as well as several other local kingdoms during the Middle Ages.[9] During World War II, refugees from eastern China fleeing from the Japanese settled in Chengdu. After the war, Chengdu was briefly the capital of the Nationalist republican government until it withdrew to Taipei on the island of Taiwan. Under the PRC, Chengdu's importance as a link between Eastern China and Western China expanded, with railways built to Chongqing in 1952, and Kunming and Tibet afterward.[9] In the 1960s, Chengdu became an important defense industry hub.

Chengdu is now one of the most important economic, financial, commercial, cultural, transportation, research and communication centers in China. Its economy is diverse, characterized by the machinery, automobile, medicine, food, and information technology industries. Chengdu is a leading financial hub, ranking 35th globally the 2021 Global Financial Centres Index.[10] Chengdu also hosts many international companies; more than 300 Fortune 500 companies have established branches in Chengdu.[11] Chengdu is the third Chinese city with two international airports after Beijing and Shanghai.[12] Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport, and the newly built Tianfu International Airport, a hub of Air China and Sichuan Airlines, is one of the 30 busiest airports in the world, and the Chengdu railway station is one of the six biggest in China. Chengdu is considered a "Beta + (global second-tier)" city classification (together with Barcelona and Washington, D.C.) according to the GaWC.[13] As of 2023, the city also hosts 23 foreign consulates, the fourth most in China behind Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.[14] Chengdu is the seat of the Western Theater Command region of the People's Liberation Army.[15] In 2023, Chengdu became the third Chinese city to host the 31st FISU Summer World University Games, after Beijing 2001 and Shenzhen 2011. Chengdu will also host the 2025 World Games. It is considered one of the best cities in China to live.[16][17] It is also a national central city of China.[18]

Chengdu is one of the world's top 25 cities by scientific research output,[19] and home to the greatest number of universities and research institutes in Western China, notably Sichuan University, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu University of Technology, Sichuan Normal University, and Xihua University.[20]

Name

[edit]The name Chengdu is attested in sources dating back to the Warring States period. It has been called the only major city in China to have remained at an unchanged location with an unchanged name throughout the imperial, republican, and communist eras.[21] However, it also had other names; for example, it was briefly known as "Xijing" (Western Capital) in the 17th century.[22] Etymology of the name is unclear. The earliest and most widely known explanation, although not generally accepted by modern scholars,[23] is provided in the 10th-century geographical work Universal Geography of the Taiping Era, which states that the ninth king of Shu's Kaiming dynasty named his new capital Chengdu after a statement by King Tai of Zhou that a settlement needed "one year to become a town, two to become a city, and three to become a metropolis."[c][24] (The character for cheng 成 may mean "turned into" while du 都 can mean either a metropolis or a capital).

The present spelling is based on pinyin romanization; its Postal Map romanization was "Chengtu." Its former status as the seat of the Chengdu Prefecture prompted Marco Polo's spellings "Sindafu," "Sin-din-fu," &c.[25][26] and the Protestant missionaries' romanization "Ching-too Foo."[27]

Although the official name of the city has remained (almost) constant, the surrounding area has sometimes taken other names, including "Yizhou." Chinese nicknames for the city include the "Turtle City", variously derived from the old city walls' shape on a map or a legend that Zhang Yi had planned their course by following a turtle's tracks; the "Brocade City" (see Sichuan brocade), a contraction of the earlier "City of the Brocade Official," after an imperial office established under the Western Han; the "Hibiscus City" (Rongcheng, 蓉城), from the hibiscus which King Meng Chang of the Later Shu ordered planted upon the city wall during the 10th century.[1][28][29]

According to Étienne de la Vaissière, "Baghshūr" (lit. 'pond of salt water') may be the Sogdian name for the region of Chengdu. This toponym is attested near Merv, but not far from Chengdu are found the large salt water wells of the Yangtze basin.[30]

Logo

[edit]The city logo adopted in 2011 is inspired by the Golden Sun Bird, an ancient relic unearthed in 2001 from the Jinsha Site.[31]

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]Archaeological discoveries at the Sanxingdui and Jinsha Site have established that the area surrounding Chengdu was inhabited over four thousand years ago, in the 18th–10th century BC. At the time of China's Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, it represented a separate ancient bronze-wielding culture that, following its partial sinification, became known to the Chinese as Shu.[32][33] Shu was conquered by Qin in 316 BC, and the settlement was re-founded by Qin general Zhang Yi.

Pre-Qin to Qin and Han dynasties

[edit]In the early stage of the Xia dynasty or even earlier, the ancient Shu Kingdom located on the Chengdu Plain has formed a relatively developed bronze civilization, becoming an important source of Chinese civilization and one of the birthplaces of the Chinese nation. According to records, there were five dynasties in the ancient Shu Kingdom, and their capitals were Qushang (now Wenjiang District, Chengdu), Piyi (now Pidu District), Xindu, and Guangdu. At the end of the Spring and Autumn period (around the 4th century BC), the fifth King Kaiming moved the capital to Chengdu. According to "Taiping Huanyu Ji," the name of the city is borrowed from the history of the establishment of the capital in the Western Zhou dynasty. The allusions of Zhou Wang Qianqi's "one year, he lived in a cluster, two years became a city, and three years Chengdu," because of the name Chengdu, it has been used to this day. Therefore, Chengdu has become a rare city in China and the world that has not changed its name since its establishment. Some people think that Chengdu is a transliteration of ancient Shu place names. There is a saying that "Guangdu, Xindu and Chengdu" are collectively referred to as the "Three Capitals of Ancient Shu." Nowadays, there are many cultural relics of ancient Shu Kingdom in Chengdu Plain, such as Sanxingdui Ruins, Jinsha Ruins, Yufu Ancient City Ruins, Wangcong Temple, etc. Jinsha Ruins located in the urban area of Chengdu is a peak of the development of ancient Shu culture.[34][35][36][37]

The Golden Mask of the Shang and Zhou dynasties at the Jinsha Site.

The ancient state of Shu was the first target to be conquered by the Qin state in the process of unifying the world. King Huiwen of Qin had prepared for this for many years, and opened up the Shiniu Road (that is, the Jinniu Road) from Qin to Shu. In 316 BC, King Huiwen of Qin took advantage of the mutual attack between Ba and Shu, and sent Sima Cuo to lead his army into Shu along the Shiniu Road, and they captured the land in a few months. After that, the king of Qin established three abolitions of Shu Hou, and finally established Shu County, and the county seat of Chengdu County was established in Chengdu, the former capital of Shu. In 311 BC, Zhang Yi of the Qin dynasty built the Chengdu city wall according to the system of the capital Xianyang, and built a large city and a small city. In 256 BC, King Zhao of Qin appointed Li Bing as the governor of Shu County. During his tenure, he presided over the construction of the world-famous Dujiangyan Water Conservancy Project. The Chengdu Plain has been fertile and wild for thousands of miles since then. After decades of operation, Chengdu replaced Guanzhong Plain in the late Qin dynasty and was called the "Land of Abundance," and this reputation has continued to this day.[38][39][40]

During the Han dynasty, the Chengdu economy, especially its brocade industry, prospered, becoming an important source of tribute to the court. The imperial court invested in Chengdu and specially set up Jinguan management and built "Jinguan City" in the southwest of Chengdu, "Jinguan City" and "Jincheng" becoming nicknames for Chengdu. In the second year of Emperor Ping of the Yuan dynasty, the population of Chengdu reached 76,000 households, or about 354,000 people, making it one of the most populous cities at that time. Towards the six major cities. In the third year of the reign of Emperor Jing of the Han dynasty (141 BC), the Wen Dang, the prefect of Shu County, established the world's earliest local government-run school, "Wenweng Shishi," in Chengdu. In the Han dynasty, Chengdu's literature and art also reached a high level. All the most famous literary masters in the Han dynasty were from Chengdu, including Sima Xiangru, Yang Xiong, and Wang Bao.[41][42]

In the former Han dynasty, the whole country was divided into 14 prefectural governors' departments, among which the Yizhou governor was established in Luoxian (now Guanghan City, Sichuan), and the governor later moved to Chengdu. In the first year of Emperor Guangwu's reign (25 years) in the Eastern Han dynasty, Gongsun Shu established himself as the emperor in Chengdu, and the country's name was "married family." In the twelfth year of Jianwu in the Later Han dynasty (36 years), the Great Sima Wuhan of the Eastern Han dynasty finally captured Chengdu after five years of war, and his family perished. In the fifth year of Zhongping (188), Emperor Ling of Han, the court accepted Liu Yan's suggestion and changed the provincial governors to state shepherds with actual recruitment and command power. In the fifth year of Chuping (194), it moved to Chengdu. At that time, the Yizhou Provincial Governor's Department was the place where the Hu people in the Western Regions were operating.[43][44][45]

Imperial era

[edit]

Under the Han, the brocade produced in Chengdu became fashionable and was exported throughout China. A "Brocade Official" (錦官; jǐnguān) was established to oversee its production and transaction. After the fall of the Eastern Han, Liu Bei ruled Shu Han, the southwestern of the Three Kingdoms, from Chengdu. His minister Zhuge Liang called the area the "Land of Abundance."[46] Under the Tang, Chengdu was considered the second most prosperous city in China after Yangzhou.[d] Both Li Bai and Du Fu lived in the city. Li Bai praised it as "lying above the empyrean." The city's present Caotang ("Grass Hall") was constructed in 1078 in honor of an earlier, more humble structure of that name erected by Du Fu in 760, the second year of his 4-year stay. The Taoist Qingyang Gong ("Green Goat Temple") was built in the 9th century.[47][48]

Chengdu was the capital of Wang Jian's Former Shu from 907 to 925, when it was conquered by the Later Tang. The Later Shu was founded by Meng Zhixiang in 934, with its capital at Chengdu. Its second and last king, Meng Chang beautified the city by ordering hibiscus to be planted upon the city walls.[49][50]

The Song conquered the city in 965, introducing the first widely used paper money in the world. Su Shi praised it as "the southwestern metropolis." At the fall of the Song, a rebel leader set up a short-lived kingdom known as Great Shu (大蜀, Dàshǔ). Allegedly the Mongols called for the death of a million people in the city but the city's population had less than 30,000 residents (not Chengdu prefecture). The aged males who had not fled were killed while in typical fashion, the women, children and artisans were enslaved and deported. During the Yuan dynasty, most of Sichuan's residents were deported to Hunan during the insurgency of the western ethnic tribes of western Sichuan. Marco Polo visited Chengdu[25][51] and wrote about the Anshun Bridge or an earlier version of it.[e]

At the fall of the Ming, the rebel Zhang Xianzhong established his Great Western Kingdom (大西) with its capital at Chengdu; it lasted only from 1643 to 1646.[22] Zhang was said to have massacred a large number of people in Chengdu and throughout Sichuan. In any case, Chengdu was said to have become a virtual ghost town frequented by tigers[52] and the depopulation of Sichuan necessitated the resettlement of millions of people from other provinces during the Qing dynasty. Following the Columbian Exchange, the Chengdu Plain became one of China's principal sources of tobacco. Pi County was considered to have the highest quality in Sichuan, which was the center of the country's cigar and cigarette production, the rest of the country long continuing to consume snuff instead.[27]

Modern era

[edit]

In 1911, Chengdu's branch of the Railway Protection Movement helped trigger the Wuchang Uprising, which led to the Xinhai Revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty.[53][54]

During World War II, the capital city of China was forced to move inland from Nanjing to Wuhan in 1937 and from Wuhan to Chengdu, then from Chengdu to Chongqing in 1938, as the Kuomintang (KMT) government under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek ultimately retreated to Sichuan to escape from the invading Japanese forces. They brought with them into Sichuan business people, workers, and academics who founded many of the industries and cultural institutions which continue to make Chengdu an important cultural and commercial production center.[43]

Chengdu became a military center for the KMT to regroup in the War of Resistance. Chengdu was beyond the reach of the Imperial Japanese ground forces and escort fighter planes. However, the Japanese frequently flew in the then-highly advanced twin-engine long-ranged G3M "Nell" medium bombers to conduct massive aerial bombardments of both civilian and military targets in Chongqing and Chengdu.[55] The massed formation of the G3M bombers provided heavy firepower against Chinese fighter planes assigned to the defense of Chongqing and Chengdu, which continued to cause problems for the Japanese attacks.[56][57]

Slow and vulnerable obsolescent Chinese fighter aircraft burning low-grade fuel were still sufficiently dangerous in the hands of capable pilots against the Japanese schnellbomber-terror bombing raiders;[58] on 4 November 1939 for instance, Capt. Cen Zeliu (Wade-Giles: Shen Tse-Liu) led his 17th Fighter Squadron, 5th Fighter Group of seven cannon-equipped Dewoitine D.510 fighters in a level head-on attack against an incoming coming raid of 72 IJANF G3M bombers (Capt. Cen chose this tactic knowing that the operation of the Hispano-Suiza HS.404 20mm autocannon in his D.510 is likely to fail under the g-loads of a high-deflection diving attack), with Capt. Cen pummeling the lead G3M of the IJN's 13th Kōkūtai's CO Captain Kikushi Okuda with cannon fire, sending the G3M crashing down in flames over Chengdu, along with three other G3M bombers destroyed in the Chengdu raid that day.[59] With the death of Captain Okuda in the air battle over Chengdu, the IJN Kaigun-daisa (海軍大佐) became the highest-ranking IJN Air officer to be killed-in-action in the War of Resistance/World War II thus far.[60]

In mid-late 1940, unknown to the Americans and European allies, the Imperial Japanese appeared in the skies over Chongqing and Chengdu with the world's most advanced fighter plane at the time: the A6M "Zero" fighter that dominated the skies over China against the increasingly obsolete Russian-made Polikarpov I-15/I-153s and I-16s that were the principal fighter planes of the Chinese Nationalist Air Force.[61] This would later prove to be a rude awakening for the Allied forces in the Pacific War following the attack on Pearl Harbor.[62] One of the first American ace fighter pilots of the war and original volunteer fighter pilot for the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, Major Huang Xinrui (nicknamed "Buffalo" by his comrades) died as a result of battling the Zero fighters along with his squadronmates Cen Zeliu and Lin Heng (younger brother of renowned architect Lin Huiyin) defending Chengdu on 14 March 1941.[63][64][61][65]

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor at the end of 1941, the United States began setting up stations at airbases in China. In 1944, the American XX Bomber Command launched Operation Matterhorn, an ambitious plan to base B-29 Superfortresses in Chengdu and strategically bomb the Japanese Home Islands.[66] The operating base was located in Xinjin Airport in the southwestern part of the Chengdu metropolitan area.[67][68] Because the operation required a massive airlift of fuel and supplies over the Himalayas, it was not a significant military success, but it did earn Chengdu the distinction of launching the first serious retaliation against the Japanese homeland.[69]

During the Chinese Civil War, Chengdu was the last city on the Chinese mainland to be held by the Kuomintang. President Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo directed the defense of the city from the Chengdu Central Military Academy (黄埔军校成都分校) until 1949, when Communist forces took the city on 27 December. The People's Liberation Army took the city without any resistance after a deal was negotiated between the People's Liberation Army and the commander of the KMT Army guarding the city. On 10 December the remnants of the Nationalist Chinese government evacuated to Taiwan.[70][71]

The Chengdu Tianfu New Area is a sustainable planned city that will be outside of Central Chengdu, and is expected to be completely built later in the decade.[when?] The city is also planned to be self-sustaining, with every residence being a two-minute walk from a park.[72]

The Great City

[edit]In 2019, Chengdu overtook Shenzhen, China's technology hub, as the best-performing Chinese economy.[73] The city has surged in population in the last two decades.[74] Investments into a Europe-Chengdu Express Railway have been made, providing even more opportunity for the city to grow.[73] As a way to preserve farmland and accommodate the growing population of Chengdu, China is building a hyper-dense satellite city centered around a central mass-transit hub called the Great City where any destination within the city is within a 15-minute walk.[75][76] This proto-type city is intended to provide affordable, high-quality lifestyle, which provides people-oriented spaces that does not require a car to navigate.[76]

Their current urban-planning focus in the city of Chengdu is to make the city 'a city within a park' rather than creating parks within a city.[74] The Great City falls in line with the Chengdu 'park city' initiative, prioritizing the environment, public space and quality of life. It will consist of 15% park and green space and be situated on a 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi) area.[76] Although 25% of the space will be dedicated to roads, one half of the roads will be pedestrian-oriented. This transit system provides direct transport to Chengdu itself.[75] It is expected that the city will consume 48% less energy than cities of similar size.[76]

The goal of the 'park city' project is to allow a city like Chengdu to compete with Beijing and Shanghai without stripping the city of its character.[74] The city of Chengdu is already known for its focus on quality of life, which includes affordable housing, good public schools, trees and bike lanes.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]

The vast plain on which Chengdu is located has an elevation ranging from 450 to 720 meters (1,480 to 2,360 feet).

Northwest Chengdu is bordered by the high and steep Longmen Mountains in the north-west and in the west by the Qionglai Mountains, the elevation of which exceeds 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and includes Miao Jiling (5,364 m, 17,598 ft) and Xiling Snow Mountain (5,164 m, 16,942 ft). The western mountainous area is also home to a large primitive forest with abundant biological resources and a giant panda habitat.[77] East of Chengdu stands the low Longquan Mountains and the west bordering area of the hilly land of middle reaches of Min River, an area noted by several converging rivers. Since ancient times, Chengdu has been known as "the Abundant Land" owing to its fertile soil, favorable climate, and novel Dujiangyan Irrigation System.[78][79][80]

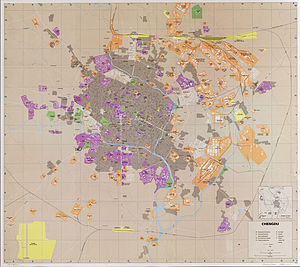

Chengdu is located at the western edge of the Sichuan Basin and sits on the Chengdu Plain; the dominating terrain is plains. The prefecture ranges in latitude from 30° 05' to 31° 26' N, while its longitude ranges from 102° 54' to 104° 53' E, stretching for 192 kilometers (119 mi) from east to west and 166 km (103 mi) south to north, administering 12,390 km2 (4,780 sq mi) of land. Neighboring prefectures are Deyang (NE), Ziyang (SE), Meishan (S), Ya'an (SW), and the Ngawa Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (N). The urban area, with an elevation of 500 m (1,600 ft), features a few rivers, three of them being the Jin, Fu, and Sha Rivers. Outside of the immediate urban area, the topography becomes more complex: to the east lies the Longquan Mountains (龙泉山脉) and the Penzhong Hills (盆中丘陵); to the west lie the Qionglai Mountains, which rise to 5,364 m (17,598 ft) in Dayi County. The highest point in Chengdu is Daxuetang (also known as Miaojiling) in Xiling Snow Mountain in Dayi County, with an altitude of 5,364 meters. The lowest point is the river bank at the exit of Tuojiang River in Jianyang City, with an altitude of 359 meters.[81][82]

Climate

[edit]Chengdu has a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa) and is largely warm with high relative humidity all year. It has four distinct seasons, with moderate rainfall concentrated mainly in the warmer months, and relieved from both sweltering summers and freezing winters. The Qin Mountains (Qinling) to the far north help shield the city from cold Siberian winds in the winter; because of this, the short winter is milder than in the Lower Yangtze. The 24-hour daily mean temperature in January is 5.9 °C (42.6 °F), and snow is rare but there are a few periods of frost each winter. The summer is hot and humid, but not to the extent of the "Three Furnaces" cities of Chongqing, Wuhan, and Nanjing, all of which lie in the Yangtze basin.[83] The 24-hour daily mean temperature in July and August is around 25 °C (77 °F), with afternoon highs sometimes reaching 33 °C (91 °F); sustained heat as found in much of eastern China is rare. Rainfall occurs most frequently and is concentrated in July and August, with very little of it in the cooler months. Chengdu also has one of the lowest annual sunshine totals nationally,[84][85] with less sunshine annually than much of Northern Europe.[citation needed] With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 15 percent in December to 32 percent in August, the city receives 1006 hours of bright sunshine annually. Spring (March–April) tends to be sunnier and warmer in the day than autumn (October–November). The annual mean is 16.9 °C (62.4 °F), and extremes have ranged from −6.5 °C (20 °F) to 39.4 °C (102.9 °F).

| Climate data for Chengdu (Shuangliu District), elevation 495 m (1,624 ft), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.5 (90.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

39.4 (102.9) |

36.2 (97.2) |

30.1 (86.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

21.3 (70.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

13.7 (56.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8.9 (0.35) |

12.4 (0.49) |

23.6 (0.93) |

47.5 (1.87) |

76.8 (3.02) |

122.5 (4.82) |

238.2 (9.38) |

198.8 (7.83) |

116.5 (4.59) |

43.1 (1.70) |

15.9 (0.63) |

7.0 (0.28) |

911.2 (35.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 7.6 | 8.0 | 10.5 | 13.5 | 13.8 | 15.7 | 17.3 | 15.7 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 146 |

| Average snowy days | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 79 | 77 | 76 | 73 | 78 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 38.3 | 54.7 | 85.2 | 116.0 | 122.1 | 110.7 | 122.1 | 132.9 | 70.5 | 54.9 | 47.7 | 37.7 | 992.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 12 | 17 | 23 | 30 | 29 | 26 | 29 | 33 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 22 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[86][87][88]all-time extreme temperature[89][90] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

[edit]Chengdu is a sub-provincial city[91] which has served as the capital of Sichuan since Chongqing's restoration to provincial status in 1997.[92] It has direct jurisdiction over 12 districts, 5 county-level cities and 3 counties:

| Administrative divisions of Chengdu | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[93] | Division | Area in km2 | Population 2020[94] | Seat | Postal code | Subdivisions[95] | |||||

| Subdistricts | Towns | Townships | Residential communities | Administrative villages | |||||||

| 510100 | Chengdu | 14,378.18 | 20,937,757 | Wuhou | 610000 | 112 | 205 | 55 | 1549 | 2735 | |

| 510104 | Jinjiang | 60.24 | 902,933 | Chenglong Road Subdistrict | 610000 | 16 | 117 | ||||

| 510105 | Qingyang | 65.89 | 955,954 | Xinhua West Road Subdistrict | 610000 | 14 | 76 | ||||

| 510106 | Jinniu | 107.03 | 1,265,398 | Fuqin Subdistrict | 610000 | 15 | 109 | ||||

| 510107 | Wuhou | 123.44 | 1,855,186 | Jiangxi Street Subdistrict | 610000 | 17 | 113 | ||||

| 510108 | Chenghua | 109.28 | 1,381,894 | Mengzhuiwan Subdistrict | 610000 | 14 | 101 | ||||

| 510112 | Longquanyi | 558.74 | 1,346,210 | Longquan Subdistrict | 610100 | 4 | 7(5) | 1 | 65 | 76 | |

| 510113 | Qingbaijiang | 392.41 | 490,091 | Hongyang Subdistrict | 610300 | 2 | 8(4) | 1 | 27 | 94 | |

| 510114 | Xindu | 480.65 | 1,558,466 | Xindu Subdistrict | 610500 | 3 | 10(10) | 128 | 127 | ||

| 510115 | Wenjiang | 276.91 | 967,868 | Liucheng Subdistrict | 611100 | 4 | 6(3) | 79 | 35 | ||

| 510116 | Shuangliu | 1,067.83 | 2,659,829 | Dongsheng Subdistrict | 610200 | 7 | 18 | 153 | 116 | ||

| 510117 | Pidu | 437.45 | 1,672,025 | Pitong Subdistrict | 611700 | 3 | 13 | 60 | 139 | ||

| 510132 | Xinjin | 329.93 | 363,591 | Wujin Subdistrict | 611400 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 26 | 80 | |

| Urban District | 3679.87 | 15,419,445 | |||||||||

| 510121 | Jintang County | 1,155.60 | 800,371 | Zhaozhen Subdistrict | 610400 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 47 | 185 | |

| 510129 | Dayi County | 1,318.80 | 515,962 | Jinyuan Subdistrict | 611300 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 66 | 152 | |

| 510131 | Pujiang County | 579.17 | 255,563 | Heshan Subdistrict | 611600 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 25 | 107 | |

| 510181 | Dujiangyan | 1,207.98 | 710,056 | Guankou Subdistrict | 611800 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 69 | 197 | |

| 510182 | Pengzhou | 1,419.38 | 780,399 | Tianpeng Town | 611900 | 1 | 19 | 102 | 251 | ||

| 510183 | Qionglai | 1,384.44 | 602,973 | Linqiong Subdistrict | 611500 | 1 | 17 | 6 | 62 | 202 | |

| 510184 | Chongzhou | 1,088.01 | 735,723 | Chongyang Subdistrict | 611200 | 1 | 18 | 6 | 65 | 188 | |

| 510185 | Jianyang | 2,215.02 | 1,117,265 | Jiancheng Subdistrict | 611400 | 4 | 25 | 29 | 49 | 796 | |

| Divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Sichuanese Pinyin | |

| Chengdu City | 成都市 | Chéngdū Shì | cen2 du1 si4 | |

| Jinjiang District | 锦江区 | Jǐnjiāng Qū | jin3 jiang1 qu1 | |

| Qingyang District | 青羊区 | Qīngyáng Qū | qin1 yang2 qu1 | |

| Jinniu District | 金牛区 | Jīnniú Qū | jin1 ȵiu2 qu1 | |

| Wuhou District | 武侯区 | Wǔhóu Qū | wu3 hou2 qu1 | |

| Chenghua District | 成华区 | Chénghuá Qū | cen2 hua2 qu1 | |

| Longquanyi District | 龙泉驿区 | Lóngquányì Qū | nong2 quan2 yi2 qu1 | |

| Qingbaijiang District | 青白江区 | Qīngbáijiāng Qū | qin1 be2 jiang1 qu1 | |

| Xindu District | 新都区 | Xīndū Qū | xin1 du1 qu1 | |

| Wenjiang District | 温江区 | Wēnjiāng Qū | wen1 jiang1 qu1 | |

| Shuangliu District | 双流区 | Shuāngliú Qū | suang1 niu2 qu1 | |

| Pidu District | 郫都区 | Pídū Qū | pi2 du1 qu1 | |

| Xinjin District | 新津区 | Xīnjīn Qū | xin1 jin1 qu1 | |

| Jintang County | 金堂县 | Jīntáng Xiàn | jin1 tang2 xian3 | |

| Dayi County | 大邑县 | Dàyì Xiàn | da4 yi2 xian3 | |

| Pujiang County | 蒲江县 | Pújiāng Xiàn | pu24 jiang1 xian3 | |

| Jianyang | 简阳市 | Jiǎnyáng Shì | jian3 yang2 si4 | |

| Dujiangyan | 都江堰市 | Dūjiāngyàn Shì | du1 jiang1 yan4 si4 | |

| Pengzhou | 彭州市 | Péngzhōu Shì | pen2 zou1 si4 | |

| Qionglai | 邛崃市 | Qiónglái Shì | qiong2 lai2 si4 | |

| Chongzhou | 崇州市 | Chóngzhōu Shì | cong2 zou1 si4 | |

- Tianfu New Area

- Chengdu Economic and Technological Development Zone

- Chengdu Hi-tech Industrial Development Zone

Cityscape

[edit]As of July 2013, the world's largest building in terms of floor area, the New Century Global Center, is located in the city. The 100-meter-tall (330 ft) structure is 500 by 400 meters (1,600 by 1,300 ft) in size with 1,700,000 square meters (18,000,000 sq ft) of floor area, housing retail outlets, a movie theaters, offices, hotels, a water park with artificial beach and waves and a Mediterranean-style village comprising a large 5-star hotel, a skating rink and a 15,000-spot parking area.[96][97]

- Gallery

-

Hejiang Pavilion

-

Sanyi Temple

-

Shamao Street

-

Mixc Complex Chengdu

-

South Renmin Road

-

Jinjiang District cityscape

-

Downtown Chengdu

-

IFS, Hongxing Road, Chengdu

-

Jin River, Shangri-la Hotel Chengdu

-

Liu Xiang Mausoleum

-

Anshun Bridge and Jinjiang River

-

Tianfu Financial Center

-

Chengdu Global Center

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 857,000 | — |

| 1964 | 1,583,000 | +84.7% |

| 1970 | 6,922,918 | +337.3% |

| 1975 | 7,819,732 | +13.0% |

| 1980 | 8,225,399 | +5.2% |

| 1985 | 8,626,770 | +4.9% |

| 1990 | 9,195,004 | +6.6% |

| 1995 | 9,715,977 | +5.7% |

| 2000 | 10,392,531 | +7.0% |

| 2005 | 10,820,285 | +4.1% |

| 2010 | 14,047,625 | +29.8% |

| 2020 | 20,937,757 | +49.0% |

| 2021 | 21,192,000 | +1.2% |

| 2022 | 21,268,000 | +0.4% |

| 2023 | 21,403,000 | +0.6% |

| Population size may be affected by changes on administrative divisions. 2021 data is year end estimate. 2022/3 from Sina. | ||

According to the 2020 Chinese census, the municipality had 20,937,757 inhabitants; the metropolitan area itself was home to 16,045,577 inhabitants including those of the 12 urban districts plus Guanghan City (in Deyang). Chengdu is the largest city in Sichuan and the fourth largest in China. 21,192,000 for 2021, adding more residents than any other city in the country.

As of 2015, the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) estimated the Chengdu metropolitan area's population to be 18.1 million.[98][99]

Culture

[edit]

In 2006, China Daily named Chengdu China's fourth-most-livable city.[100]

Literature

[edit]Some of China's most important literature comes from Chengdu. The city has been home to literary giants, such as Sima Xiangru and Yang Xiong, two masters of Fu, a mixture of descriptive prose and verse during the Tang dynasty; Li Bai and Du Fu, the most eminent poets of the Tang and Song dynasties respectively; Yang Shen'an, a famous scholar of the Ming dynasty; and Guo Moruo and Ba Jin, two well-known modern writers. Chang Qu, a historian of Chengdu during the Jin dynasty, compiled the earliest local historical records, the Record of Hua Yang State. Zhao Chongzuo, a poet in Chengdu during the Later Shu Kingdom, edited Among the Flowers, the first anthology of Ci in China's history. Meng Chang, the king of Later Shu, wrote the first couplet for the Spring Festival, which says, "A harvest year accepts celebrations, good festivals foreshadow long springs."[citation needed]

In 2023, Chengdu hosted the 81st World Science Fiction Convention, having beat out Winnipeg, Canada, in site-selection voting in 2021.[101]

Fine art

[edit]During the period of the Five Dynasties, Huang Quan, a painter in Chengdu, initiated the Fine-Brush Flower-and-Bird Painting School with other painters. At that time, "Hanlin Painting Academy" was the earliest royal academy in China.[102][103]

Religion

[edit]

Chengdu contains official,[104] Roman Catholic[105] and Protestant congregations, some of which are underground churches.

The Apostolic Vicariate of Szechwan (now known as Roman Catholic Diocese of Chengdu) was established on 15 October 1696. Artus de Lionne, a French missionary of Paris Foreign Missions Society, was appointed as the first Apostolic Vicar.[citation needed]

In 1890, the Canadian Methodist Mission was searching for more stations in Asia. In February 1891, Dr. Virgil Chittenden Hart, who had been Superintendent of the New York Methodist Mission Society of Central China recommended that Chengtu be its first Mission sight. During the meeting, it was proposed he lead this contingency; having built western hospitals, Boy's and Girl's schools at Missions he established on the Yangtze and Gan Rivers from 1866 – 1888. On 9 May 1891 Dr. Virgil Hart arrived in Chengtu and two weeks later bought a home and had it subdivided into living quarters and a dispensary, for the later arriving Missionary staff to move into.[106]

On 24 June 1892, the doors of Chengtu's first Protestant Mission Headquarters were opened with over one thousand people of the community attending. The first Methodist religious service was held the following Sunday with only several attendants. The first western dispensary in Sichuan was opened 3 November 1892 with sixteen patients seeking care. The mission site became so popular that a larger space was secured near Chengtu's East Gate in the spring of 1893. This site is where the city's first Methodist church (Sï-Shen-Tsï Methodist Church) and hospital were built. These were later razed by rioting Chinese in 1895 and the Mission staff retreated to Chongqing and later Shanghai to escape the marauders. Dr. Virgil Hart traveled to Peking to demand redress and full payment of retribution was collected from Sichuan Viceroy Liu Ping Chang. The mission compound was quickly rebuilt only to be destroyed once more in the riots of 1901. These were rebuilt a third time and later missionaries would relocate and expand the Boys' and Girls' Schools just south of the city, dedicating the Divinity College as Hart College in 1914; a part of the West China Union University, that is now Sichuan University and the West China School of Medicine (Huaxiyida).[107][108][109] During the Cultural Revolution, the Sï-Shen-Tsï Methodist Church building was no longer in use and the building was entrusted to the nearby Chengdu City Second People's Hospital for management. The hospital used the chapel as a kindergarten and the office of the hospital equipment department. In 1984, the hospital returned the chapel building to the church.[110]

In December 2018 the authorities attempted to close a 500-member underground church, the Early Rain Covenant Church, led by Pastor Wang Yi. Over 100 members of the church were arrested including the pastor and his wife. The church's kindergarten and theological college were raided and the church's media outlets were closed down. Before his arrest, church member Li Yingqiang declared: "Even if we are down to our last five, worship and gatherings will still go on because our faith is real. […] Persecution is a price worth paying for the Lord." Police are said to have told one member that the church had been declared an illegal organisation. Chinese media were banned from reporting the events. Video footage which found its way onto western social media showed arrests and photographs alleged to be of injuries inflicted by the police.[111][112][113] From a photo of Ms. Jiang's detention warrant it appears that the authorities have charged the church's leaders with "inciting subversion of state power," which carries a maximum sentence of 15 years.[114]

In 2012, a Chabad Jewish Center was established in Chengdu, after moving five times, a permanent location was secured at Wuhou District.[115][116]

Theater

[edit]

The saying "Shu opera towers above all other performances in the world" reflects the achievement of Sichuan opera and Zaju (an ancient form of comedic drama involving dancing, singing, poetry, and miming). In the city, the first named opera "Bullfighting" was written in the Warring States period. The first detailed recorded opera was staged in the royal court of Shu Kingdom during the Three Kingdom period. China's first clearly recorded Zaju was also performed in Chengdu. Tombs of witty Han dynasty poets were excavated in Chengdu. And face-changing masks and fire breathing remain hallmarks of the Sichuan opera.[117][118][119][120]

Language

[edit]The native language in Chengdu is Sichuanese, otherwise referred as Sichuan dialect. More precisely, "Chengdu Dialect" (成都话/成都方言) is widely used in lieu of "Sichuanese" due to the largely different accents of Sichuanese speakers residing elsewhere.[121][122][123]

Culinary art and tea culture

[edit]

The distinct characteristic of Sichuan cuisine is the use of spicy chilies and peppercorns. Famous local dishes include Mapo doufu, Chengdu Hot pot, and Dan Dan Mien. Both Mapo Doufu and Dan Dan Mien contain Sichuan peppers. An article[124] by the Los Angeles Times (2006) called Chengdu "China's party city" for its carefree lifestyle. Chengdu has more tea houses and bars than Shanghai despite having less than half the population. In 2023, there were more than 30,000 teahouses in Chengdu,[125] and there were 3,566 legally registered bars, nightclubs, and dance halls in the city.[126] A statistical report in 2019 showed that Chengdu had more bars than Shanghai, becoming the city with the most bars in China.[127] Chengdu's tea culture dates back over a thousand years, including its time as the starting point of the Southern Silk Road.[128]

Common side dishes popular in Chengdu include noodles, wontons, dumplings, pastries, tangyuan (sweet rice balls), drinks, salads and soups.[citation needed]

Chengdu is an officially recognised UNESCO City of Gastronomy.[129]

Teahouse

[edit]Tea houses are ubiquitous in the city and range from ornate traditional establishments with bamboo furniture to simple modern tea houses. Teas on offer include jasmine, longjing and biluochun tea. Tea houses are popular venues for playing mahjong, getting a massage or one's ears clean.[130] Some larger tea houses offer live entertainment such as Sichuan opera performances.[131]

Hot pot

[edit]

Chengdu is known for its hot pot.[132] Hot pot is a traditional Sichuanese dish, made by cooking vegetables, fish, and/or meat in boiling spicy broth. A type of food suitable for friends' gathering, hot pot attracts both local people and tourists. Hot pot restaurants can be found at many places in Chengdu.[133][134]

Mahjong

[edit]

Mahjong has been an essential part of most local peoples' lives. After daytime work, people gather at home or in the tea houses on the street to play Mahjong. On sunny days, local people like to play Mahjong on the sidewalks to enjoy the sunshine and also the time with friends.

Mahjong is the most popular entertainment choice among locals for several reasons. Chengdu locals have simplified the rules and made it easier to play as compared to Cantonese Mahjong. Also, Mahjong in Chengdu is a way to meet old friends and to strengthen family relationships. In fact, many business people negotiate deals while playing Mahjong.[135] Furthermore, the elderly like to play Mahjong because they believe Mahjong makes them think and prevents dementia.[citation needed]

Rural tourism: Nong Jia Le

[edit]Chengdu claims to have first practiced the modern business model of 'Nong Jia Le' (Happy Rural Homes). It refers to the practice of suburban and rural residents converting their houses into restaurants, hotels and entertainment spaces in order to attract city dwellers.[136]

Nong Jia Le features different styles and price levels and have been thriving around Chengdu. They provide gateways for city dwellers to escape the city, offer delicious and affordable home-made dishes, and provide mahjong facilities.[137]

Main sights

[edit]World natural and cultural heritage sites

[edit]Mount Qingcheng

[edit]

Mount Qingcheng is amongst the most important Taoism sites in China. It is situated in the suburbs of Dujiangyan City and connected to downtown Chengdu 70 km (43 mi) away by the Cheng-Guan Expressway.[138]

With its peak 1,600 m (5,200 ft) above sea level, Mount Qingcheng enjoys a cool climate, but remains a lush green all year round and surrounded by hills and waterways. Mount Qingcheng's Fujian Temple, Tianshi Cave, and Shizu Hall are some of the existing more well-known Taoist holy sites. Shangqing Temple is noted for an evening phosphorescent glow locally referred to as "holy lights."[138]

Dujiangyan Irrigation System

[edit]The Dujiangyan Irrigation System (58 km (36 mi) away from downtown Chengdu) is the oldest existing irrigation project in the world with a history of over 2000 years diverting water without a dam to distribute water and filter sand with an inflow-quantity control. The system was built by Libing and his son. The irrigation system prevents floods and droughts throughout the Plain of Chengdu.[139][140]

Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries

[edit]

Covering a total of 9,245 km2 (3,570 sq mi) over 12 distinct counties and 4 cities, Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, lie on the transitional alp-canyon belt between the Sichuan Basin and the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. It is the largest remaining continuous habitat for giant pandas and home to more than 80 percent of the world's wild giant pandas. Globally speaking, it is also the most abundant temperate zone of greenery. The reserves of the habitat are 100–200 km (62–124 mi) away from Chengdu.[141][142]

The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries are the most well-known of their kind in the world, with Wolong Nature Reserve, generally considered as the "homeland of pandas." It is a core habitat with unique natural conditions, complicated landforms, and a temperate climate with diverse wildlife. Siguniang Mountain, sometimes called the "Oriental Alpine" is approximately 230 km (140 mi) away from downtown Chengdu, and is composed of four adjacent peaks of the Traversal Mountain Range. Among the four peaks, the fourth and highest stands 6,250 m (20,510 ft) above sea level, and is perpetually covered by snow.[143][144]

Culture of poetry and the Three Kingdoms

[edit]Wuhou Shrine

[edit]

Wuhou Shrine (Temple of Marquis Wu; 武侯祠) is perhaps the most influential museum of Three Kingdoms relics in China. It was built in the Western Jin period (265–316) in the honor of Zhuge Liang, the famous military and political strategist who was Prime Minister of the Shu Han State during the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). The Shrine highlights the Zhuge Liang Memorial Temple and the Hall of Liu Bei (founder of the Shu Han state), along with statues of other historical figures of Shu Han, as well as cultural relics like stone inscriptions and tablets. The Huiling Mausoleum of Liu Bei represents a unique pattern of enshrining both the emperor and his subjects in the same temple, a rarity in China.[145][146][147]

Du Fu thatched cottage

[edit]Du Fu was one of the most noted Tang dynasty poets; during the Lushan-Shi Siming Rebellion, he left Xi'an (then Chang'an) to take refuge in Chengdu. With the help from his friends, the thatched cottage was built along the Huanhua Stream in the west suburbs of Chengdu, where Du Fu spent four years of his life and produced more than 240 now-famous poems. During the Song dynasty, people started to construct gardens and halls on the site of his thatched cottage to honor his life and memory. Currently, a series of memorial buildings representing Du Fu's humble life stand on the river bank, along with a large collection of relics and various editions of his poems.[148][149]

Ancient Shu civilization

[edit]Jinsha Site

[edit]

The Jinsha Site are the first significant archeological discovery in China of the 21st century and were selected in 2006 as a "key conservation unit" of the nation. The Jinsha Relics Museum is located in the northwest of Chengdu, about 5 km (3.1 mi) from downtown. As a theme-park-style museum, it is for the protection, research, and display of Jinsha archaeological relics and findings. The museum covers 300,000 m2 (3,200,000 sq ft), and houses relics, exhibitions, and a conservation center.[150]

Golden Sun Bird

[edit]

The Golden Sun Bird was excavated by archaeologists from the Jinsha Ruins on 25 February 2001. In 2005, it was designated as the official logo of Chinese cultural heritage by the China National Relic Bureau.[151][152]

The round, foil plaque dates back to the ancient Shu area in 210 BC and is 94.2 percent pure gold and extremely thin. It contains four birds flying around the perimeter, representing the four seasons and directions. The sun-shaped cutout in the center contains 12 sunlight beams, representing the 12 months of a year. The exquisite design is remarkable for a 2,200-year-old piece.[153][154]

Sanxingdui Museum

[edit]Situated in the northeast of the state-protected Sanxingdui Site, The original complex of Sanxingdui Museum was founded in August 1992 and opened in 1997. It is the representative work of the master architect Zheng Guoying. The original museum covers an area of 1,000 acres and was rated as the first batch of national first-class museums.[155]

The new complex of Sanxingdui Museum was founded in March 2022. It covers an area of 54,400 square meters, which is about 5 times the size of the old museum. It was built for new cultural relics after major archaeological excavations. It displays more than 2,000 precious cultural relics such as bronze, jade, gold, pottery, and bone, and comprehensively and systematically displays the archaeological excavations and latest research results of Sanxingdui.[155]

The main collection highlights the Ancient City of Chengdu, Shu State & its culture, while displaying thousands of valuable relics including earthenware, jade wares, bone objects, gold wares, and bronzes that have been unearthed from Shang dynasty sacrificial sites.[156]

Buddhist and Taoist culture

[edit]Daci Temple

[edit]The Daci Temple (大慈寺), a temple in downtown Chengdu was first built during the Wei and Jin dynasties, with its cultural height during the Tang and Song dynasties. Xuanzang, a Tang dynasty monk, was initiated into monkhood and studied for several years here; during this time, he gave frequent sermons in Daci Monastery.[157]

Wenshu Monastery

[edit]Also named Xinxiang Monastery, Wenshu Monastery (文殊院) is the best preserved Buddhist temple in Chengdu. Initially built during the Tang dynasty, it has a history dating back 1,300 years. Parts of Xuanzang's skull are held in consecration here (as a relic). The traditional home of scholar Li Wenjing is on the outskirts of the complex.[158][159]

Baoguang Buddhist Temple

[edit]Located in Xindu District, Baoguang Buddhist Temple (宝光寺) enjoys a long history and a rich collection of relics. It is believed that it was constructed during the East Han period and has appeared in written records since the Tang dynasty. It was destroyed during the Ming dynasty in the early 16th century. In 1607, the ninth year of the reign of the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty, it was rebuilt.[160][161]

Qingyang Palace

[edit]

Located in the western part of Chengdu, Qingyang Palace (青羊宫) is not only the largest and oldest Taoist temple in the city, but also the largest Taoist temple in Southwestern China. The only existing copy of the Daozang Jiyao (a collection of classic Taoist scriptures) is preserved in the temple.[162][163]

According to history, Qingyang Temple was the place where Lao Tzu preached his famous Dao De Jing to his disciple, Ying Xi.[162]

Featured streets and historic towns

[edit]Kuanzhaixiangzi Alleys

[edit]Kuanzhaixiangzi Alleys (宽窄巷子) were first built during the Qing dynasty for Manchu soldiers. The lanes remained residential until 2003 when the local government turned the area into a mixed-use strip of restaurants, teahouses, bars, avant-garde galleries, and residential houses. Historic architecture has been well preserved in the Wide and Narrow lanes.[164][165][166]

Jinli

[edit]

Nearby Wuhou Shrine, Jinli is a popular commercial and dining area resembling the style of traditional architecture of western Sichuan. "Jinli" (锦里) is the name of an old street in Chengdu dating from the Han dynasty and means "making perfection more perfect."[167][168]

The ancient Jinli Street was one of the oldest and the most commercialized streets in the history of the Shu state and was well known throughout the country during the Qin, Han and Three Kingdoms periods. Many aspects of the urban life of Chengdu are present in the current-day Jinli area: teahouses, restaurants, bars, theaters, handicraft stores, local snack vendors, and specialty shops.[168][169]

Huanglongxi Historic Town

[edit]

Facing the Jinjiang River to the east and leaning against Muma Mountain to the north, the ancient town of Huanglongxi is approximately 40 km (25 mi) southeast of Chengdu. It was a large military stronghold for the ancient Shu Kingdom. The head of the Shu Han State in the Three Kingdoms period was seated in Huanglongxi, and for some time, the general government offices for Renshou, Pengshan, and Huayang counties were also located here. The ancient town has preserved the Qing dynasty architectural style, as seen in the design of its streets, shops, and buildings.[170]

Chunxi Road

[edit]

Located in the center of downtown Chengdu, Chunxi Road (春熙路) is a trendy and bustling commercial strip with a long history. It was built in 1924 and was named after a part of the Tao Te Ching. Today, it is one of the most well-known and popular fashion and shopping centers of Chengdu, lined with shopping malls, luxury brand stores, and boutique shops.[171][172]

Anren Historic Town

[edit]Anren Historic Town is located 39 km (24 mi) west of Chengdu. It was the hometown of Liu Wencai, a Qing dynasty warlord, landowner and millionaire. His 27 historic mansions have been well preserved and turned into museums. Three old streets built during the Republic of China period are still being used today by residents. Museums in Anren have a rich collection of more of than 8 million pieces of relics and artifacts. A museum dedicated to the memorial of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake was built in 2010.[173][174][175]

Luodai Historic Town

[edit]Luodai was built, like many historic structures in the area, during the period of the Three Kingdoms. According to legend, the Shu Han emperor Liu Shan dropped his jade belt into a well when he passed through this small town. Thus, the town was named 'lost belt' (落带). It later evolved into its current name 洛带 with the same pronunciation, but a different first character.[176]

Luodai Historic Town is one of the five major Hakka settlements in China. Three or four hundred years ago, a group of Hakka people moved to Luodai from coastal cities. It has since grown into the largest community for Hakka people.[177]

Economy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

China's state council has designated Chengdu as the country's western center of logistics, commerce, finance, science and technology, as well as a hub of transportation and communication. It is also an important base for manufacturing and agriculture.

According to the World Bank's 2007 survey report on global investment environments, Chengdu was declared "a benchmark city for investment environment in inland China."[178]

Also based on a research report undertaken by the Nobel economics laureate, Dr. Robert Mundell and the celebrated Chinese economist, Li Yining, published by the State Information Center in 2010, Chengdu has become an "engine" of the Western Development Program, a benchmark city for investment environment in inland China, and a major leader in new urbanization.[179]

In 2010, 12 of the Fortune 500 companies, including ANZ Bank, Nippon Steel Corporation, and Electricité de France, have opened offices, branches, or operation centers in Chengdu, the largest number in recent years. Meanwhile, the Fortune 500 companies that have opened offices in Chengdu, including JP Morgan Chase,[180] Henkel,[181] and GE,[182] increased their investment and upgraded the involvement of their branches in Chengdu. By the end of 2010, over 200 Fortune 500 companies had set up branches in Chengdu, ranking it first in terms of the number of Fortune 500 companies in Central and Western China. Of these, 149 are foreign enterprises and 40 are domestic companies.[183][181]

According to the 2010 AmCham China White Paper on the State of American Business in China, Chengdu has become a top investment destination in China.[184]

The main industries in Chengdu—including machinery, automobile, medicine, food, and information technology—are supported by numerous large-scale enterprises. In addition, an increasing number of high-tech enterprises from outside Chengdu have also settled down there.[185][186]

Chengdu is becoming one of the favorite cities for investment in Central and Western China.[187] Among the world's 500 largest companies, 133 multinational enterprises have had subsidiaries or branch offices in Chengdu by October 2009.[187] These MNEs include Intel, Cisco, Sony and Toyota that have assembly and manufacturing bases, as well as Motorola, Ericsson, and Microsoft that have R&D centers in Chengdu.[187] The National Development and Reform Commission has formally approved Chengdu's proposed establishment of a national bio-industry base there.[188] The government of Chengdu had unveiled a plan to create a 90-billion-CNY bio pharmaceutical sector by 2012.[189] China's aviation industries have begun construction of a high-tech industrial park in the city that will feature space and aviation technology.[190] The local government plans to attract overseas and domestic companies for service outsourcing and become a well-known service outsourcing base in China and worldwide.[191]

In the middle of the 2000s, the city expanded urban infrastructure and services to nearby rural communities in an effort to improve rural living conditions.[192]: 167

Electronics and IT industries

[edit]Chengdu has long been an established national electronics and IT industry hub. Chengdu's growth accelerated alongside the growth of China's domestic telecom services sector, which along with India's together account for over 70 percent of the world telecommunications market. Several key national electronics R&D institutes are located in Chengdu. Chengdu Hi-tech Industrial Development Zone has attracted a variety of multinationals, at least 30 Fortune 500 companies and 12,000 domestic companies, including Intel, IBM, Cisco, Nokia, Motorola, SAP, Siemens, Canon, HP, Xerox, Microsoft, Tieto, NIIT, MediaTek, and Wipro, as well as domestic powerhouses such as Lenovo.[193] Dell opened its second major China operations center in 2011[194] in Chengdu as its center in Xiamen expands in 2010.[195]

Intel Capital acquired a strategic stake in Primetel, Chengdu's first foreign technology company in 2001.[196][197] Intel's Chengdu factory, set up in 2005 is its second in China, after its Shanghai factory, and the first such large-scale foreign investment in the electronics industry in interior mainland China.[198] Intel, the world's largest chipmaker, has invested US$600 million in two assembly and testing facilities in Chengdu.[199] Following the footsteps of Intel, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), the world's third largest foundry, set up an assembly and testing plant in Chengdu in 2006.[200] AMD, Intel's rival, had set up an R&D center in this city in 2008.[201][202]

In November 2006, IBM signed an agreement with the Chengdu High-Tech Zone to establish a Global Delivery Center, its fourth in China after Dalian, Shanghai and Shenzhen, within the Chengdu Tianfu Software Park. Scheduled to be operational by February 2007, this new center will provide multilingual application development and maintenance services to clients globally in English, Japanese and Chinese, and to the IBM Global Procurement Center, recently located to the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen.[203] On 23 March 2008, IBM announced at the "West China Excellent Enterprises CEO Forum" that the southwest working team of IBM Global Business Services is now formally stationed in Chengdu. On 28 May 2008, Zhou Weikun, president of IBM China disclosed that IBM Chengdu would increase its staff number from the present 600 to nearly 1,000 by the end of the year.[204][205]

In July 2019, Amazon Web Services, the cloud computing company, signed a deal with the Chengdu High-Tech Zone to establish an innovation center. This project was intended to attract international business and enterprise into the area, promote cloud computing in China, and develop artificial intelligence technologies.[206][207]

Chengdu is a major base for communication infrastructure, with one of China's nine top level postal centers and one of six national telecom exchanges hub.[citation needed]

In 2009, Chengdu hosted the World Cyber Games Grand Finals (11–15 November). It was the first time China hosted the world's largest computer and video game tournament.[208]

Financial industry

[edit]Chengdu is a leading financial hub in the Asia-Pacific region and ranks 35th globally and 6th in China after (Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing, Shenzhen and Guangzhou) in the 2021 Global Financial Centres Index.[10] Chengdu has attracted a large number of foreign financial institutions, including Citigroup, HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank, JPMorgan Chase, ANZ and MUFG Bank.[209]

ANZ's data services center, established in 2011 in Chengdu, employs over 800 people, and in March 2019 the bank recruited further staff to support its data analytics and big data efforts.[210] In 2020, ANZ temporarily repurposed its Chengdu data center to an IT helpdesk, as part of the bank's pandemic response.[211]

Historically, Chengdu has marked its name in the history of financial innovation. The world's first paper currency 'Jiao Zi' was seen in Chengdu in the year 1023, during the Song dynasty.[212]

Now, Chengdu is not only the gateway of Western China for foreign financial institutions, but also a booming town for Chinese domestic financial firms. The Chinese monetary authority, People's Bank of China (China's central bank), set its southwestern China headquarters in Chengdu City.[213] In addition, almost all domestic banks and securities brokerage firms located their regional headquarters or branches in Chengdu. At the same time, the local financial firms of Chengdu are strengthening their presences nationally, notably, Huaxi Securities, Sinolink Securities, and Bank of Chengdu. Moreover, on top of banks and brokerage firms, the flourish of local economy lured more and more financial service firms to the city to capitalise on the economic growth. Grant Thornton, KPMG, PWC and Ernst & Young are the four global accountants and business advisers with Western China head offices in the city.[214][215]

It is expected that by 2012, value-added financial services will make up 14 percent of the added-value service industry and 7 percent of the regional GDP. By 2015, those figures are expected to grow to 18 percent and 9 percent respectively.[216]

Modern logistic industry

[edit]Because of its logistic infrastructure, professional network, and resources in science, technology, and communication, Chengdu has become home to 43 foreign-funded logistic enterprises, including UPS, TNT, DHL, and Maersk, as well as a number of well-known domestic logistic enterprises including COSCO, CSCL, SINOTRANS, CRE, Transfar Group, South Logistic Group, YCH, and STO. By 2012, the logistic industry in Chengdu will realize a value added of RMB 50 billion, with an average annual growth exceeding 18 percent. Ten new international direct flights will be in service; five railways for five-scheduled block container trains will be put into operation; and 50 large logistic enterprises are expected to have annual operation revenue exceeding RMB 100 million.[217][218]

Modern business and trade

[edit]Chengdu is the largest trade center in western China with a market covering all of Sichuan province, exerting influence on a population of 250 million in six provinces, cities, and districts in western China. Chengdu ranks first among cities in western China in terms of the scale of foreign investment in commerce and trade. Out of the 40 World Top 250 retail enterprises based in China, 15 have opened branches in Chengdu. In downtown Chengdu, there are 71 department stores whose business area exceeds 10,000 sq. m, with the total business area reaching 2,600,000 sq. m. By 2012, total retail sales of consumer goods in Chengdu will exceed RMB 300 billion, up 18 percent annually on average; the total wholesales will exceed RMB 400 billion, with an annual increase of 25 percent. Total retail sales of the catering industry will exceed RMB 60 billion, up 20 percent annually; and the total exports and imports of Chengdu will be above US$35 billion, increasing 30 percent annually.

Convention and exhibition industry

[edit]Boasting the claim as "China’s Famous Exhibition City," Chengdu takes the lead in central and western China for its scale of convention economy. It has become one of the five largest convention and exhibition cities in China. In 2010, direct revenue from the convention and exhibition industry was RMB 3.2 billion, with a year-on-year growth of 26.9 percent. The growth reached a historical high.

More than 13.2 million people have come to Chengdu to participate in conventions and exhibitions from foreign countries and other parts of China. Numerous convention and exhibition companies have invested in Chengdu such as the UK-based Reed Exhibition, as well as domestic companies such as the Chinese European Art Center, Sanlian Exhibition, and Eastpo International Expo.

Software and service outsourcing industry

[edit]Chengdu is one of the first service outsourcing bases in China. More than 150,000 people in Chengdu are engaged in software-related work. Among the Top 10 service outsourcing enterprises in the world, Accenture, IBM, and Wipro are based in Chengdu. In addition, 20 international enterprises including Motorola, Ubi Soft Entertainment, and Agilent, have set up internal shared service centers or R&D centers in Chengdu. Maersk Global Document Processing Center and Logistic Processing Sub-center, DHL Chengdu Service Center, Financial Accounting Center for DHL China, and Siemens Global IT Operation Center will be put into operation. In 2010, offshore service outsourcing in Chengdu realized a registered contract value of US$336 million, 99 percent higher than the previous year.

New energy industry

[edit]Chengdu is the "National High-Tech Industry Base for New Energy Industry," as approved by the National Development and Reform Commission. Leading enterprises are operating in Chengdu and providing research and technology support such as Tianwei New Energy Holding Co., Ltd., Sichuan Sanzhou Special Steel Tube Co., Ltd., Zhejiang Tianma Bearing Co., Ltd., and key research institutions such as the Nuclear Power Institute of China, Southwestern Institute of Physics, Southwest Electric Power Design Institute.

In 2010, the new energy enterprises above realized 31.1 billion RMB in revenue from main operations, 43.2 percent more than the previous year. Chengdu ranked first again in the list of China's 15 "Cities with Highest Investment Value for New Energies" released at the beginning of 2011, and Shuangliu County under its jurisdiction entered "2010 China's Top 100 Counties of New Energies." By 2012, Chengdu's new energy industry will realize an investment over 20 billion RMB and sales revenue of 50 billion RMB.

Electronics and information industry

[edit]Chengdu is home to the most competitive IT industry cluster in western China, an important integrated circuit industry base in China, and one of the five major national software industry bases.

Manufacturing chains are already formed in integrated circuits, optoelectronics displays, digital video & audio, optical communication products, and original-equipment products of electronic terminals, represented by such companies as IBM, Intel, Texas Instruments, Microsoft, Motorola, Nokia, Ericsson, Dell, Lenovo, Foxconn, Compal, Wistron, and others.

Automobile industry

[edit]Chengdu has built a comprehensive automobile industry system, and preliminarily formed a system integrated with trade, exhibitions, entertainment, R&D, and manufacturing of spare parts and whole vehicles (e.g., sedans, coaches, sport utility vehicles, trucks, special vehicles). There are whole vehicle makers, such as Dongfeng-PSA (Peugeot-Citroën), Volvo, FAW-Volkswagen, FAW-Toyota, Yema, and Sinotruk Wangpai, as well as nearly 200 core parts makers covering German, Japanese, and other lines of vehicles.

In 2011, Volvo announced that its first manufacturing base in China with an investment of RMB 5.4 billion was to be built in Chengdu. By 2015, the automobile production capacity of Chengdu's Comprehensive Function Zone of Automobile Industry is expected to reach 700,000 vehicles and 1.25 million in 2020.[219]

Modern agriculture

[edit]Chengdu enjoys favorable agricultural conditions and rich natural resources. It is an important base for high-quality agricultural products. A national commercial grain and edible oil production base, the vegetable and food supply base as well as the key agricultural products processing center and the logistics distribution center of western China are located in Chengdu.

Defense industry

[edit]Chengdu is home to many defense companies such as the Chengdu Aircraft Company, which produces the recently declassified J-10 Vigorous Dragon combat aircraft as well as the JF-17 Thunder, in a joint collaborative effort with Pakistan Air Force. Chengdu Aircraft Company has also developed the J-20 Mighty Dragon stealth fighter. The company is one of the major manufacturers of Chinese Military aviation technology.

Industrial zones

[edit]Chengdu Hi-tech Comprehensive Free Trade Zone

[edit]

Chengdu Hi-tech Comprehensive Free Trade Zone was established with the approval of the State Council on 18 October 2010 and passed the national acceptance on 25 February 2011.[citation needed] It was officially operated in May 2011. Chengdu High-tech Comprehensive Free Trade Zone is integrated and expanded from the former Chengdu Export Processing Zone and Chengdu Bonded Logistics Center. it is located in the Chengdu West High-tech Industrial Development Zone, with an area of 4.68 square kilometers and divided into three areas A, B and C. The industries focus on notebook computer manufacturing, tablet computer manufacturing, wafer manufacturing and chip packaging testing, electronic components, precision machining, and biopharmaceutical industry.[citation needed] Chengdu Hi-Tech Comprehensive Free Trade Zone has attracted top 500[citation needed] and multinational enterprises such as Intel, Foxconn, Texas Instruments, Dell, Morse and so on.

In 2020, the Chengdu Hi-Tech Comprehensive Free Trade Zone achieved a total import and export volume of 549.1 billion yuan (including Shuangliu Sub-zone), accounting for 68% of the province's total foreign trade import and export volume, ranking No.1 in the national comprehensive free trade zones for three consecutive years.[220]

Chengdu Economic and Technological Development Zone

[edit]Chengdu Export Processing Zone

[edit]Chengdu Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

[edit]Chengdu National Cross-Strait Technology Industry Development Park

[edit]This was established in 1992 as the Chengdu Taiwanese Investment Zone.[221]

Built environments

[edit]In 1988, The Implementation Plan for a Gradual Housing System Reform in Cities and Towns marked the beginning of overall housing reform in urban areas of China.[222] More than 20 real estate companies set up in Chengdu, which was the first step for Chengdu's real estate development.

The comprehensive Funan River renovation project in the 1990s had been another step towards promoting Chengdu environmental development.[223][224] The Funan River Comprehensive Improvement Project won the UN-Habitat Scroll of Honour Award in 1998,[225][226] as well as winning the "Local Initiative Award" by the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives in 2000.[227]

Chengdu started the Five Main Roads & One Bridge project in 1997. Three of the roads supported the east part of the city, the other two led to the south. It established the foundation of the Eastern and Southern sub-centers of Chengdu. The two major sub-centers determined people's eastward and southward living trends. Large numbers of buildings appeared around the east and south of the 2nd Ring Road. The Shahe River renovation project together with Jin River project also set off a fashion for people living by the two rivers. It was said that the map of Chengdu should update every three months.[228]

A speculative housing boom occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[192]: 167 In 2000, dozens of commercial real estate projects also appeared.[229] While promoting the real estate market, the Chinese government encouraged citizens to buy their own houses by providing considerable subsidies at a certain period. Houses were included in commodities.

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Chengdu is the third Chinese city with two international airports (Shuangliu International Airport and Chengdu Tianfu International Airport) after Beijing and Shanghai.[12] Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport is located in Shuangliu County 16 km (9.9 mi) southwest of downtown. Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport is the busiest airport in Central and Western China and the nation's fourth-busiest airport in 2018, with a total passenger traffic of 53 million in 2018.[230]

Chengdu airports (including Shuangliu International Airport and Tianfu International Airport) is also a 144-hour visa-free transit port for foreigners from 53 countries[231] Besides, Chengdu airports also offer 24-hour visa-free transit for most nationals when having a stopover in Chengdu.

Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport has two runways and is capable of landing the Airbus A-380, currently the largest passenger aircraft in operation. Chengdu is the fourth city in China with two commercial-use runways, after Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. On 26 May 2009, Air China, Chengdu City Government and Sichuan Airport Group signed an agreement to improve the infrastructure of the airport and increase the number of direct international flights to and from Chengdu. The objective is to increase passenger traffic to more than 40 million by 2015, making Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport the fourth-largest international hub in China, after Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, top 30 largest airports in the world.[232][233] Chengdu Shuangliu Airport ranked the No.1 and No.2 busiest airport in China in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

A second international airport, the Chengdu Tianfu International Airport currently with two main terminals and three runways, opened in June 2021. The new airport is 51 kilometers (32 mi) southeast of the city and will have a capacity to handle between 80 and 90 million passengers per year.

Railway