Boynton Beach, Florida

Boynton Beach, Florida | |

|---|---|

Marina Village of Boynton Beach | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: Boynton, B-town | |

| Motto: America's Gateway to the Gulfstream | |

Location within Palm Beach County and Florida | |

| Coordinates: 26°31′41″N 80°4′35″W / 26.52806°N 80.07639°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Palm Beach |

| Settled (Boynton Settlement) | 1895 |

| Incorporated | 1920 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission-Manager |

| • Mayor | Ty Penserga |

| • Vice Mayor | Thomas Turkin |

| • Commissioners | Angela Cruz, Woodrow L. Hay, and Aimee Kelley |

| • City Manager | Dan Dugger |

| • City Clerk | Maylee De Jesus |

| Area | |

• Total | 16.57 sq mi (42.91 km2) |

| • Land | 16.16 sq mi (41.85 km2) |

| • Water | 0.41 sq mi (1.06 km2) 2.3% |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 80,380 |

| • Density | 4,974.93/sq mi (1,920.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Zip Codes | 33424–33426, 33435–33437,33474 |

| Area code(s) | 561, 728 |

| FIPS code | 12-07875[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0279303[2] |

| Website | www |

Boynton Beach is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. It is situated about 57 miles (92 km) north of Miami. The 2020 census recorded a population of 80,380. Boynton Beach is located in the Miami metropolitan area, which was home to 6,138,333 people at the 2020 census. The city is named after Nathan Boynton, a Civil War major and Michigan politician who became one of the first settlers in the area in 1895. Boynton Beach is located north of Delray Beach, south of Hypoluxo and Lantana, and east of Golf, while the municipalities of Briny Breezes, Gulf Stream, Manalapan, and Ocean Ridge are situated to the east across the Intracoastal Waterway.

Native Americans inhabited modern-day Boynton Beach thousands of years ago, with a burial mound west of the city including artifacts dating as far back as roughly 150 BCE. The first non-indigenous settlers, Dexter Hubel and his family, arrived in 1877. Major Boynton moved to present-day Boynton Beach in 1895, building the Boynton Hotel and bringing contingents from Michigan, many of whom practiced farming or established businesses in the vicinity of Ocean Avenue. Byrd and Fred Dewey filed the original plat for the Town of Boynton in 1898, although official incorporation did not occur until 1920. The oceanfront section of Boynton Beach split off in 1931 and became Ocean Ridge in 1939. Boynton Beach's population grew rapidly in the first few decades following World War II, with more than a three-fold increase in the 1950s, while development of the city expanded westward, particularly in the 1980s.

Today, Boynton Beach is the third-most populous municipality in Palm Beach County, behind only West Palm Beach and Boca Raton. The area along Congress Avenue south of Gateway Boulevard includes a large concentration of restaurants and retail stores at the Boynton Beach Mall, the Boynton Town Center, and Renaissance Commons. Boynton Beach also has several arts and culture facilities, such as the Boynton Woman's Club and Schoolhouse Children's Museum & Learning Center.

History

[edit]

- See also William S. Linton

Archaeological evidence indicates Native American inhabitation of the region dating back thousands of years, with Ais, Calusas, Jaegas, Mayaimis, and Tequesta settling in or near modern-day Palm Beach County.[4] A complex of mounds west of present-day Boynton Beach and near the Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge includes shards of pottery possibly from 150 BCE. An excavation of the site also yielded beads and glass from as recently as the 16th century, which are believed to have been influenced by the Spanish.[5]: 10–11

Captain James A. Armour, head keeper of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, filed the first land claim in modern-day Boynton Beach in 1875, although it is unlikely he lived there.[5]: 11 Two years later, Dexter Hubel of Michigan and his family settled in the area, but they had to live at the Orange Grove House of Refuge in present-day Delray Beach until their house was built.[5]: 12

In 1894, two years before Henry Flagler built his railroad, a former American Civil War major named Nathan Boynton first set eyes on the area that now bears his name.[5]: 14 Boynton hailed from Port Huron, Michigan.[5]: 13 He was so impressed by the natural beauty of the year-round sunshine and pristine beaches, he built the famous Boynton Hotel, where he also spent winters with his family. The hotel, which opened in 1897, included accommodations for 100 guests and 5 guest cottages.[5]: 15 Major Boynton died on May 27, 1911, in Port Huron,[6] but the hotel lasted until 1925.[5]: 32 Several commercial and residential buildings also sprang up along Ocean Avenue in the late 1890s, including the first post office in 1896.[7]

The first settlers, whom Boynton had brought along from Michigan, soon realized that many fruits and vegetables thrived in the fertile climate. Pineapples, tomatoes, mangoes, and citrus fruit were packed in crates and shipped across the country on the newly built Florida East Coast Railroad. Alonzo King and Samuel Cade, both African American farmers, taught these early settlers methods for cultivating muck soil and dealing with the presence of mosquitos and rattlesnakes.[7]

Boynton Beach was founded on September 26, 1898, when Byrd Spilman Dewey and her husband Fred S. Dewey filed the original plat in the Dade County courthouse for the Town of Boynton.[8] Fred S. Dewey, one of Flager's secretaries, bought a large area of land west of the Intracoastal Waterway earlier that year. He subdivided the land into 2.5 acre (1.0 ha) tracts for agricultural uses, which he sold to settlers and hotel workers. Buyers of these tracts also received a plot within the residential sections of the townsite.[5]: 17

A wood-frame schoolhouse opened in 1900 at Ocean Avenue and Seacrest Boulevard, replacing a smaller, temporary building.[5]: 20 By then, the town had a population of 83.[7] Just four years later, a second, two-room school building opened as the community continued to grow quickly.[5]: 20 Overcrowding at the school at Ocean Avenue and Seacrest Boulevard also led to the construction of another school in 1913, a two-story concrete building with six classrooms.[5]: 25 This building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was converted into the Schoolhouse Children's Museum & Learning Center in 2001.[9]

The first bridge crossing the Intracoastal Waterway opened in 1911 at Ocean Avenue. During the same year, the Boynton Woman's Club and the Florida Federal of Women's Clubs established the first library in Boynton, then staffed by volunteers. The 1910s also saw the creation of the town's first bank in 1915 and first ocean road (State Road A1A) in 1916.[5]: 7

The town of Boynton was officially incorporated in 1920 upon the approval of 48 out of the 50 qualified voters who met at the Boynton Lumber Club on April 14. G. E. Coon became the first mayor, Fred Benson became the first town marshall, and A. A. Atwater, J. P. Bowen, C. M. Jensen, A. C. Shepherd, and W. S. Shepherd became the first aldermen.[5]: 26 Shortly before the incorporation of Boynton, the 1920 census recorded a population of 671 people in Palm Beach County's fourth precinct, which also included Hypoluxo and the area that now comprises Ocean Ridge.[10] The name "Boynton Beach" was first used by a community that broke off from the Town of Boynton in 1931. In 1939, that community changed its name to "Ocean Ridge" while The Town of Boynton took the name "Boynton Beach" in 1941.[11]

Utility services also began in Boynton in the early 1920s. John Meredith brought electricity to the town in 1921, the same year as the installation of a sewage system. Additionally, in 1923, a municipal water system began operating.[5]: 7 Telephone service arrived in Boynton near the end of the 1920s.[5]: 8

Boynton Beach Oceanfront Park is located just north of the original Boynton Hotel site. In 1921, the Town of Boynton acquired the beach site from Lewis S. Howe by eminent domain for park and recreation purposes. The beach casino was built in 1928 and featured a large dining hall, locker rooms and showers and residents used the casino for parties and social gatherings. The casino was demolished in 1967 and the property remained part of the beach park. From the 1920s to today, Boynton Beach Oceanfront Park has been popular with residents and visitors alike. In the mid-1990s, the park underwent a major renovation during which the boardwalk was rebuilt out of recycled plastic. Boynton Beach's Oceanfront Park was voted the best family beach in Palm Beach County by The Palm Beach Post in 2001. In 2011 the boardwalk was renovated again, replacing the plastic with ipe (pronounced ee-pay) wood (commonly known as Brazilian walnut). In 2012 improvements were made to the buildings along the boardwalk, including total refurbishment of the restrooms.

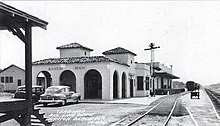

In 1926, the Seaboard Air Line Railway entered what was then simply Boynton, spurring land development a mile inland near the Seaboard station, including the town's first planned subdivision, Lake Boynton Estates.[12] As land became more valuable, areas along the Intracoastal Waterway and the Federal Highway in Boynton also saw housing developments. To the west, many dairies were founded so that the Boynton area became the main milk supplier for Palm Beach County.[13] By the 1970s, the dairies were no longer profitable and these lands too were converted to housing developments.

Three hurricanes affected Boynton between 1926 and 1928.[5]: 7–8 The 1928 Okeechobee hurricane in particular caused significant impacts, destroying 46 homes and 18 buildings,[14] including a church, a hotel, and the town hall.[5]: 8 Additionally, the storm damaged 255 homes and 34 buildings,[14] including the high school, where 15 people suffered injuries after auditorium roof collapsed.[15] The hurricane rendered 56 families homeless and caused approximately $1 million in damage.[5]: 8 The Boynton town government faced financial struggles in the aftermath of the 1928 hurricane and during the Great Depression, but received some assistance from the Florida Legislature and negotiated with bondholders for additional debt relief. Funds from the state also resulted in the resurfacing of Dixie Highway,[5]: 38 while federal funds were used to construct a new bridge across the Intracoastal Waterwater in 1935.[5]: 39

Boynton Beach grew very rapidly in the 1950s, with its population expanding from 2,542 people in 1950 to 10,467 people in 1960, a 311.8% increase. Significant construction projects during the decade included a new city hall at Boynton Beach Boulevard and Seacrest Boulevard in 1958 and Bethesda Memorial Hospital in 1959. The expansion of beachfront recreation facilities also occurred as the city purchased more coastal properties.[10]

During the 1960s, the city constructed a civic center in 1960, a public library in 1961, and a new water treatment plant in 1962. A second bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway opened in 1967 along 15th Avenue (Woolbright Road).[5]: 8 The decade also marked beginning of the construction of Interstate 95 through the city (completed in 1977),[5]: 42–43 the westward expansion of Boynton Beach Boulevard in 1962,[16] the southward extension of Congress Avenue in 1966.[17] Additionally, residential projects such as the large Hampshire Gardens, Leisureville, and Sterling Village sprang up, causing further growth and economic development.[5]: 42–43 A few civil rights movement protests also occurred in Boynton Beach during the 1960s, including a sit-in at the Royal Castle Restaurant and the arrival of approximately 30 African Americans at a whites-only section of the beach in 1962.[16]

Several developments also brought a substantial economic boost to Boynton Beach in the 1980s. First, Motorola opened a new paging plant in the city in 1983,[5]: 43 although the complex closed in 2004, about 10 years after its peak, when the facility employed approximately 3,500 people.[18] Next, the Boynton Beach Mall and Quantum Corporate Park opened in 1985 and 1988, respectively.[16] Additionally, Tri-Rail began operating in 1989, opening its station in Boynton Beach in December of that year.[19] Each of these factors attracted more businesses to the area and generated rapid population increases in the city's western suburbs.[5]: 43

Hurricane Wilma struck Boynton Beach on October 24, 2005, causing widespread damage to homes and businesses. In 2006, the city government authorized the demolition of the historic Seaboard rail station, which had survived intact in private hands since passenger service to the station halted in 1971.[12]

On March 8, 2022, Ty Penserga was elected mayor of Boynton Beach in Florida, making him the first openly gay mayor of the city as well as the first out LGBTQ Asian American mayor elected in Florida state history. A high school biology and chemistry teacher, Penserga was sworn into office by State Attorney Dave Aronberg.[20]

Crime

[edit]The year 2006 saw an increase in gang-related violent crime. This mirrored a similar increase across Palm Beach County. A gang-related shooting that resulted in a death at the city's popular Boynton Beach Mall on Christmas Eve of 2006 caught the national attention on many news networks, such as CBS.[21] There were ten known operating gangs in the city as of 2007, according to police, including the notorious South Florida Haitian Zoe Pound gang.[22] As of 2009, countywide gang violence had fallen three percent.[23]

On January 27, 2012, Mayor Jose Rodriguez was suspended from office by the state governor for trying to influence a police investigation into his personal affairs.[24]

The crime rate started decreasing in 2017 and attained its lowest number in 20 years in 2020.[25] According to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement's 2020 Annual Crime Report, the total crime rate decreased by 28 percent in the city compared to 2019 and 64 percent compared to 2001. Violent crime, which includes murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault, decreased 8.5 percent. Property crime, which includes burglary, larceny and motor vehicle theft, dropped by 32.2 percent. Florida's total crime volume dropped 14.1 percent compared to 2019.[26]

Boynton Beach Police Chief Michael G. Gregory attributed the decrease to focused efforts, an all-hands-on-deck approach and "using a multitude of tactics and crime fighting strategies that are constantly evolving based on crime patterns".[25]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1,053 | — | |

| 1940 | 1,326 | 25.9% | |

| 1950 | 2,542 | 91.7% | |

| 1960 | 10,467 | 311.8% | |

| 1970 | 18,115 | 73.1% | |

| 1980 | 35,624 | 96.7% | |

| 1990 | 46,194 | 29.7% | |

| 2000 | 60,389 | 30.7% | |

| 2010 | 68,217 | 13.0% | |

| 2020 | 80,380 | 17.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] | |||

| Historical demographics | 2020[28] | 2010[29] | 2000[30] | 1990[31] | 1980[32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 47.3% | 53.6% | 64.4% | 73.5% | 78.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15.4% | 12.8% | 9.2% | 6.8% | 4.0% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 30.6% | 29.6% | 22.5% | 19.0% | 17.2% |

| Asian and Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 2.4% | 2.1% | 1.5% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Native American (non-Hispanic) | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | |

| Some other race (non-Hispanic) | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.2% | < 0.1% | |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | 3.4% | 1.5% | 2.0% | N/A | N/A |

| Population | 80,380 | 68,217 | 60,389 | 46,194 | 35,624 |

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[33] | Pop 2010[34] | Pop 2020[35] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 38,897 | 36,534 | 37,989 | 64.41% | 53.56% | 47.26% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 13,585 | 20,218 | 24,604 | 22.50% | 29.64% | 30.61% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 82 | 100 | 92 | 0.14% | 0.15% | 0.11% |

| Asian (NH) | 898 | 1,438 | 1,896 | 1.49% | 2.11% | 2.36% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 24 | 21 | 18 | 0.04% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

| Some other race (NH) | 105 | 179 | 602 | 0.17% | 0.26% | 0.75% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,234 | 1,025 | 2,763 | 2.04% | 1.50% | 3.44% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 5,564 | 8,702 | 12,416 | 9.21% | 12.76% | 15.45% |

| Total | 60,389 | 68,217 | 80,380 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 80,380 people, 30,370 households, and 17,274 families residing in the city.[36]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 68,217 people, 29,172 households, and 15,743 families residing in the city.[37]

In 2010, the population density was 4,217.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,628.4/km2). The 29,172 housing units (19.8% of which were vacant) averaged 2,190.04 inhabitants per square mile (845.6/km2) inhabitants per square mile.[38]

In 2010, in the town, the age distribution was 21.5% at 65 or older, 19.3% under 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 26.9% from 25 to 44, and 24.6% from 45 to 64; the median age was 41.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 89 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87 females. Around 25.1% of the households in 2010 had children under the age of 18 living with them, 16.6% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no spouse present, and 43.1% were not families. About 34.3% of all households were made up of one individual, and 15.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.3, and the average family size was 3.0.[38]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, 60,389 people and 15,673 families resided in the city. The population density was 3,803.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,468.3/km2). There were 30,643 housing units at an average density of 1,930.0 persons per square mile (745.0 persons/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.36% White (64.4% were Non-Hispanic White),[39] 22.89% African American, 0.22% Native American, 1.52% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 2.36% from other races, and 2.60% from two or more races. About 9.21% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[40]

In 2000, there were 26,210 households, out of which 22.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.4% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a woman whose husband did not live with her, and 40.2% were non-families. About 33.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 17.8% had someone living alone who were 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.87.[40]

In 2000, in the city the population was spread out in 2000, with 19.9% under the age of 18, 6.4% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 25.8% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 87.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.5 males.[40]

As of 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $39,845, and the median income for a family was $47,546. Males had a median income of $32,503 versus $26,399 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,573. About 7.4% of families and 10.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.9% of those under age 18 and 7.2% of those age 65 or over.[40]

Native speakers of English accounted for 80.09% of all residents in 2000, while speakers of French Creole comprised 7.51%, Spanish was at 7.30%, French consisted of 1.02%, Italian at 0.97%, and German made up 0.87% of the population.[41]

Economy

[edit]In 2021, Boynton Beach had a labor force of 41,266 people, while 25,208 people 16 years of age or older were not in the labor force.[42] By number of employees, the largest employers in Boynton Beach in 2020 were Bethesda Memorial Hospital and the city government, with the former employing 2,579 people and the latter employing 843 people.[43]: 111–25 However, as of 2020, only 11.9% of jobs in Lake Worth Beach were held by city residents, with the most common other residencies being Boca Raton (12.1%), Delray Beach (8.0%), West Palm Beach (7.0%), Palm Springs (4.3%), Fort Lauderdale (2.8%), Deerfield Beach (2.1%), Pompano Beach (1.5%), Wellington (1.3%), and Palm Beach Gardens (1.3%).[44] Among the city's labor force, the most common professions as of 2021 included educational services, and health care and social assistance (22.0%); retail (14.6%); professional, scientific, and management, and administrative and waste management services (14.2%); arts, entertainment, and recreation, and accommodation and food services (11.4%); and finance and insurance, and real estate and rental and leasing (7.0%).[42]

Schools

[edit]Like all of Palm Beach County, Boynton Beach is served by the School District of Palm Beach County. As of 2006, it was the fifth largest school district in Florida and the twelfth largest school district in the United States.

Elementary schools:

- Citrus Cove Elementary School

- Crosspointe Elementary

- Forest Park Elementary

- Manatee Elementary

- Galaxy Elementary School

- Poinciana Elementary School (magnet school for math, science and

Middle schools:

- Congress Middle School

High schools:

- Boynton Beach Community High School

- South Tech Academy Charter High School

Historic preservation

[edit]The Boynton Beach Historical Society formed in 1968. According to its website, the historical society's mission is "to act as a living repository for Boynton Beach's traditions and history, to interpret items of historical and antiquarian significance, and to promote a better understanding of the history of Boynton Beach, Palm Beach County and the State of Florida." The organization does not have a physical location. As such, the Boynton Beach Public Library houses its archives and records. In addition to Boynton Beach, the historical society also maintains materials relevant to the histories of Briny Breezes, Gulf Stream, Hypoluxo,[45] Lake Worth Beach,[46] Lantana, Manalapan, and Ocean Ridge, as well as areas from the city's western boundaries to U.S. Route 441.[45]

The city's Historic Resources and Preservation Board lists 170 historic sites, including commercial and residential buildings, bridges, cemeteries, churches, social clubs, and other architectural features.[47] Additionally, the board maintains two heritage trails, one for the 30 sites listed in downtown and another for the 3 historic cemeteries.[48][49] Federally, Boynton Beach has two structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places – the Boynton Woman's Club and the Boynton School, now known as the Schoolhouse Children's Museum & Learning Center.[50]

Public transportation

[edit]

Boynton Beach is served by a Tri-Rail station of the same name linking Boynton Beach to West Palm Beach to the north and Miami to the south. It is also serviced by local buses provided by PalmTran.[51]

Culture

[edit]Boynton Beach has an arts district.[52] It was named as one of South Florida's "emerging neighborhoods" by the South Florida Business Journal in 2017.[53]

Controversy

[edit]Boynton Beach commissioned a mural showing three of its firefighters, unveiled in 2020, for a window covering at a new fire station. The mural depicted former fire chief Glenn Joseph, and former deputy fire chief Latosha Clemons, both of whom are Black. Clemons was the city's first Black female fire fighter. The mural depicted both of them as White, and Clemons sued the city for defamation, libel and negligence. The city has since removed the mural and settled the lawsuit.[54][55]

Notable people

[edit]- Tanner Anderson, MLB and Chinese Professional Baseball League player[56]

- Ramon Perez Blackburn, actor-singer-dance[57]

- Danielle Bregoli, rapper, social media personality[58]

- Marlon Byrd, former MLB outfielder for several teams, ending his career with the Cleveland Indians[58]

- Jeremy Cain, former NFL long snapper for the Chicago Bears, Tennessee Titans, and Jacksonville Jaguars[59]

- Hector Camacho, Puerto Rican boxer, resided there

- Noah Centineo, actor[60]

- Charles Cornelius, former NFL and CFL player[61]

- Byrd Spilman Dewey, author and town of Boynton co-founder[8]

- Craig Erickson, former NFL quarterback, drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles and played for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Indianapolis Colts, and the Miami Dolphins, and in college for Miami[62]

- Johnny Farrell, golfer, 1928 U.S. Open champion[63]

- Gar Finnvold, former MLB player for the Boston Red Sox[56]

- Brandon Fletcher (born 1987), Internet entrepreneur

- James J. Greco, businessman, lived in town 2011-2016[64]

- Jayron Hosley, former NFL cornerback for the New York Giants[65]

- Lamar Jackson, NFL quarterback for the Baltimore Ravens, 2019 NFL MVP[58]

- Kelani Jordan, professional wrestler, WWE NXT (NXT Women's North American Champion)

- Ricardo Jordan, former MLB pitcher[56]

- Michael Kelly (baseball), MLB player for the Cleveland Guardians[56]

- Ryan Klesko, MLB player

- Sean Labanowski (born 1992), Israeli-American basketball player in the Israeli National League

- Dov Markus (born 1946), Israeli-American soccer player

- Vincent Mason, rapper, producer, DJ, and one third of hip hop trio De La Soul[66]

- Hilary McRae, singer, songwriter[58]

- Tristan Nunez, racing driver[67]

- Almerin C. O'Hara, US Army major general[68]

- Titus O'Neil, professional wrestler[58]

- Harvey Eugene Oyer III, attorney and author[69]

- Charlie W. Pierce, Florida pioneer and author[70]

- Rick Rhoden, former MLB player[56]

- Otis Thorpe, NBA basketball player[58]

- Trea Turner, MLB Player with the Philadelphia Phillies, 2019 World Series champion[56]

- Howard E. Wasdin, sniper in Navy SEAL Team Six[71]

- Vince Wilfork, former NFL nose tackle for the New England Patriots and Houston Texans, two-time Super Bowl champion (XXXIX and XLIX)[58]

- Mark Worrell, MLB Player[72]

- Danny Young, MLB player with the Atlanta Braves[56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Boynton Beach, Florida

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Native Americans". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y City of Boynton Beach, Florida, Historic Sites Survey (PDF) (Report). Research Atlantica, Inc. September 1996. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Maj. N. S. Boynton Died in Michigan Home on May 27". The Miami Metropolis. June 3, 1911. p. 12. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Boynton and Boynton Beach". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Pedersen, Ginger L. (April 9, 2013). When Curiosity Changes your Life. palmbeachpast.org. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ Colavecchio, Shannon (September 9, 2001). "Students young, old enjoy schoolhouse". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1B. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Boynton Beach's Population History". Boynton Beach Historical Society. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "History of Ocean Ridge". Archived from the original on March 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Pesantes, Erika (June 14, 2007). "Angry neighborhood challenges City Hall". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Pedersen, Ginger L. (October 23, 2010). "The Last Cows of Boynton". Palmbeachpast.org. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Palm Beach Hurricane—92 Views. Chicago, Illinois: American Autochrome Company. 1928. p. 5. OCLC 08648474.

- ^ "36 Lives Lost is Storm Toll Over Florida". Miami Herald. September 18, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Boynton Beach Timeline – Expansion". City of Boynton Beach. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Maki, Josi (July 5, 1981). "Yesteryear". The Palm Beach Post. p. 6. Retrieved June 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pounds, Stephen (December 17, 2004). "Motorola closes last Boynton building". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1D. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wallace, Debra L. (December 19, 1989). "Boynton Beach Tri-Rail station opens". Sun Sentinel. p. 3B. Retrieved May 31, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Galassi, Josh (May 19, 2022). "Ty Penserga's historic mayoral win made Florida even gayer". Queerty. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Shooting At Fla. Mall Leaves One Dead". CBS News. December 25, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Gangs in Palm Beach County". May 21, 2007. Archived from the original on May 21, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ "Gang violence falls in Palm Beach County as law enforcement focuses on prevention". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. February 15, 2009. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Kleinberg, Eliot (January 30, 2012). "Boynton city attorney suggests timetable for mayor's temporary replacement". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "Crime rate drops again in Boynton Beach". BBPD. June 24, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "UCR". www.fdle.state.fl.us. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "P2: HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT ... - Census Bureau Table". P2 | HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "P2: HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT ... - Census Bureau Table". P2 | HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "PL002: HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT ... - Census Bureau Table". PL002 | HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE [73]. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population General Population Characteristics Florida Section 1 of 2" (PDF). Florida: 1990, Part 1. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "General Population Characteristics FLORIDA 1980 Census of Population" (PDF). 07553445v1chA-Cpt11sec1ch002.pdf. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Boynton Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Boynton Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau .

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Boynton Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau .

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Boynton Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Boynton Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010" (PDF). Florida Office of Economic & Demographic Research. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Demographics of Boynton Beach, FL". MuniNetGuide.com. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "MLA Data Center Results for Boynton Beach, Florida". Modern Language Association. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "Selected Economic Characteristics". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For The Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2020 (PDF) (Report). City of Boynton Beach. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Home Destination Analysis". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b "Contact". Boynton Beach Historical Society. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Local History Archives". City of Boynton Beach. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Historic Sites by Type". City of Boynton Beach Historic Resources and Preservation Board. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "City of Boynton Beach Downtown Heritage Trail" (PDF). City of Boynton Beach. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "City of Boynton Beach Cemetery Heritage Trail" (PDF). City of Boynton Beach. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Florida - Palm Beach County". nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Palm Tran Maps and Schedules". Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Poletti, Julio (January 31, 2019). "Day trip: Boynton Beach things to do". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Emerging Neighborhoods: Boynton Beach blossoms with art, breweries and development (Photos)". bizjournals.com. November 7, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Vigdor, Neil (October 11, 2021). "Florida City Sued Over Mural Depicting First Black Female Firefighter as White". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Boynton Beach settling lawsuit with Black female firefighter". Sun-sentinel.com. October 13, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Major League Baseball Players Born in Florida". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Eyman, Scott (August 26, 2007). "'The Blackburn Twins ... were elegant.'". The Palm Beach Post. p. 4J. Retrieved June 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Seltzer, Alexander (August 9, 2017). "Did you know? 7 Boyntonians who made it big in sports, stage, screen". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Jeremy Cain". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Diaz, Johnny (August 28, 2018). "Noah Centineo, who has become a Netflix teen heartthrob is from Miami and Boca Raton". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Charles Cornelius". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Craig Erickson". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Golf". Detroit Free Press. June 16, 1988. p. 2E. Retrieved June 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Having Words With: James Greco". nrn.com. February 20, 2012

- ^ "Jayron Hosley". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Lieser, Jason (August 16, 2016). "Tre Mason's recent incidents a contrast to past with father from De La Soul". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "IMSA SportsCar Championship 2016 Media Guide" (PDF). IMSA. p. 78. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Hudson, Edward (July 8, 1987). "Gen. Almerin C. O'Hara Dies; Led the Military In New York". The New York Times. New York, New York. p. D23 – via TimesMachine.

- ^ Oyer III, Harvey (June 24, 2019). "In the footsteps of my grandfather". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Waresh, Julie (May 23, 2001). "City's first postmaster named 'Great Floridian'". The Palm Beach Post. p. B5. Retrieved June 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Frias, Carlos (May 8, 2011). "The secret SEALs: Boynton native provides inside peek at elite team". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Leonard's Worrell glad for shot with Padres". The Palm Beach Post. February 12, 2009. p. 2C. Retrieved June 5, 2023.